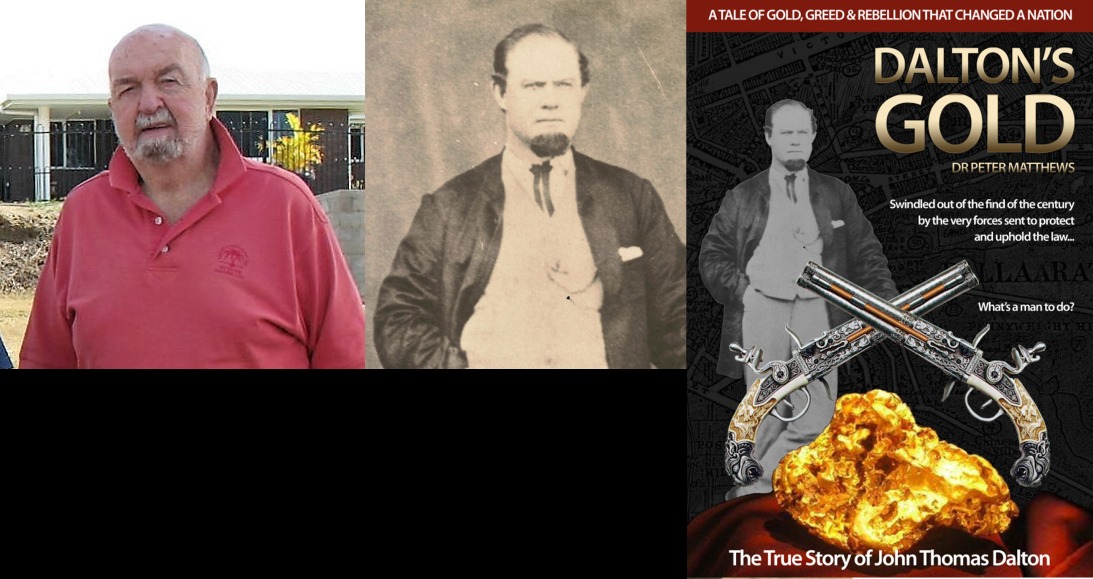

To download a copy of this research paper in pdf format, please click here: The Tinworths – A True Rags to Riches Story

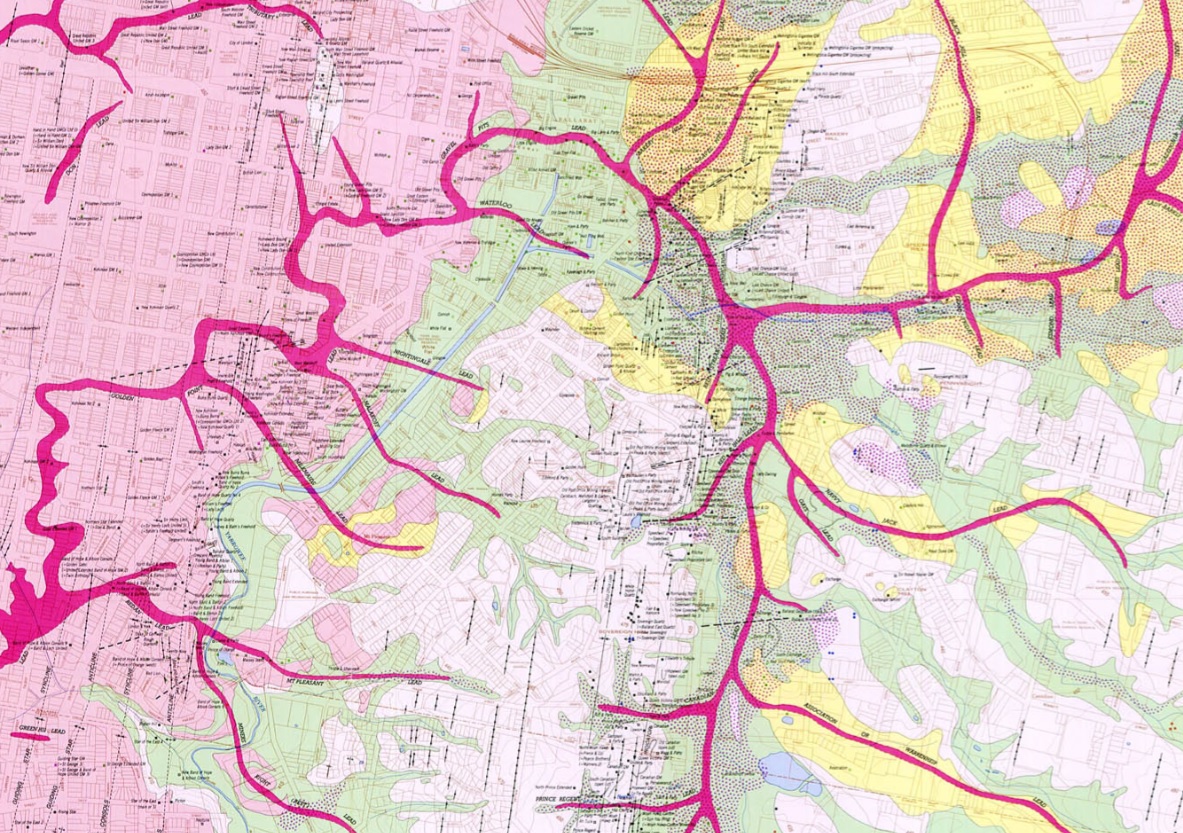

The Tinworths of Ballarat

A True Rags to Riches Story

Prepared for BBC Television Program “Who do You Think You Are?”

by Dr Peter D Matthews

If democracy means opposition to a tyrannical press,

a tyrannical people or a tyrannical government,

then I have ever been, I am still, and will ever remain, a democrat.

(Peter Lalor, before the Victorian Legislative Assembly)1

Setting the Scene

The Eureka Stockade is often characterized as a handful of drunken, brawling foreign (predominantly Irish) rebels who refused to pay their taxes. Nothing could be further from the truth.

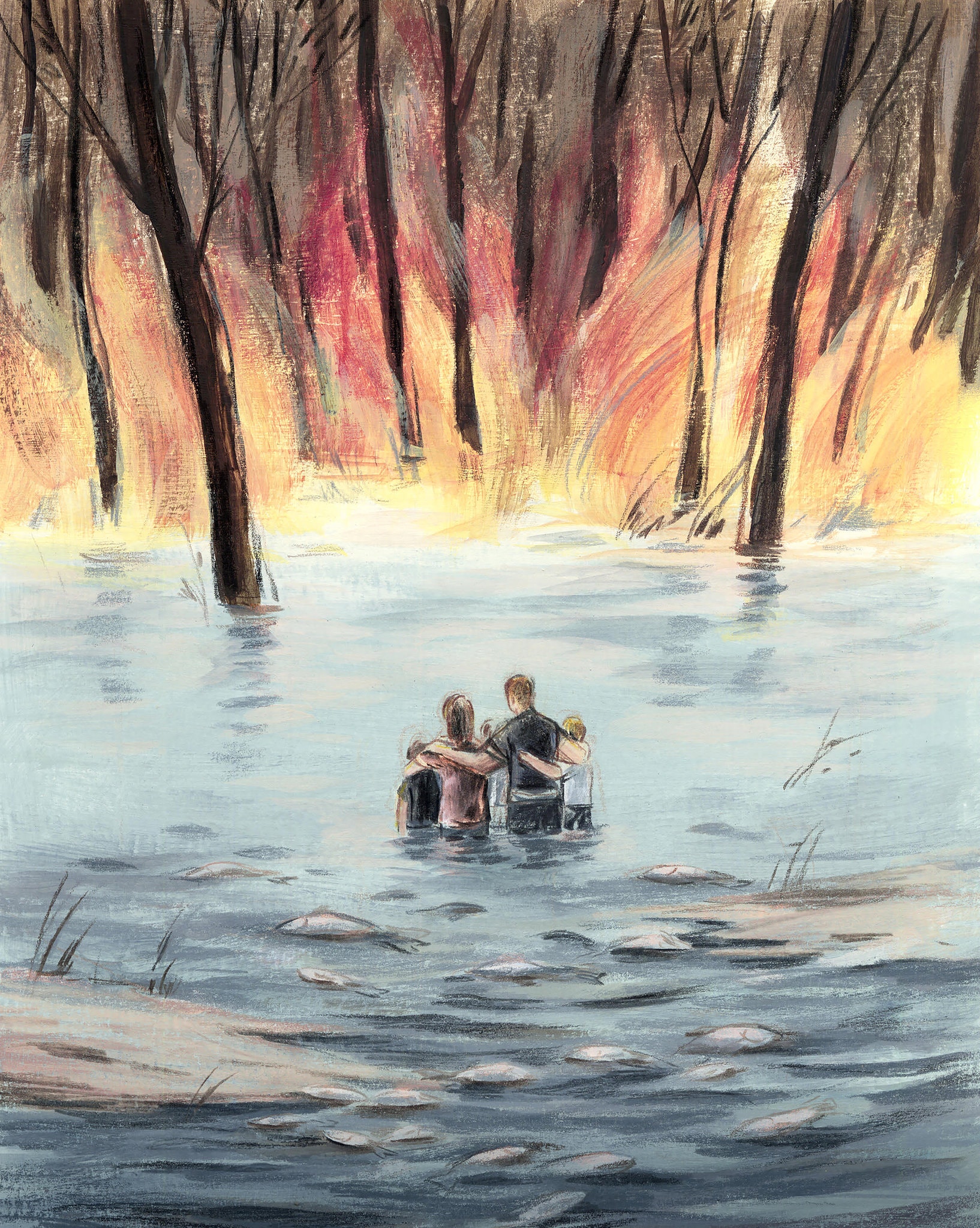

Many of the miners of Ballarat immigrated from across the world because of stories filled with promise and glorious gold nuggets. When they arrived, they found the goldfields of Ballarat were teaming with people in search of their dream, and a colonial government that charged a whopping thirty shillings licence fee each month, merely because of Governor Hotham’s haemorrhaging government purse. The paper licence had to be kept on their person and licence checks were carried out twice weekly with digger reports of being beaten with fists, boots, rifle butts, while threatened of being run through with bayonets if they did not cooperate. If a digger dare run, they were shot in the back by the Gold Commissioner’s police, who were fondly named “blue-pissants” because of their despicable cowardly and callous nature.

Diggers throughout the Victorian goldfields could not buy property or lay mining claims (tenements) over the land they worked and were afforded no representation. With no notice, they could be moved on and their gold seized anytime the Gold Commissioner saw fit, such as the case with John Thomas Dalton and the “Lady Hotham Nugget”, might I add, with no right of recourse. For many, their dream of a new land with promise and unbridled wealth where they could start a family had faded into the distant past. The colonial government attacked their Church, their drinking hole, and threatened their very lives in the name of taxation. It was simply too much to bear and the diggers joined together in unity under the Southern Cross flag on Bakery Hill. John Thomas Dalton recounted, “The Southern Cross was our date with destiny. We were called to stand and were joined by our faith in God’s promise to release us from tyranny.”

Gold Commissioner Robert Rede believed the diggers complaints were nothing more than “democratic nonsense” and called in the “red-coats” from Melbourne, Geelong and Castlemaine to quell the diggers. Rede in a premediated strike, came upon the Stockade at dawn on Sunday 3rd December 1854 with 296 heavily armed mounted and foot police, military infantry, cavalry, with officers from the 12th, 40th and 99th regiments, when most of the diggers had gone home to their families. It was a massacre that outraged the entire Australian population. 114 men mostly of English and Australian origin were captured and tortured until 13 men were dragged off to face trial in Melbourne. The government’s attempt to hang the diggers of Eureka failed. The entire proceedings were filled with corruption, perjury and malice on behalf of the government. Each verdict of ‘not guilty’ came from the jury within minutes of retiring. All the government achieved was making

a mockery of the judicial system, which produced widespread resentment, proving their own incompetence in office.

News of the digger’s plight had reached Queen Victoria, which brought about a raft of changes, including the Colonial Office enacting the Constitution of Victoria on 16 July 1855. Peter Lalor, the elected representative member of the diggers, became the first Member of the Legislative Council for the seat of Ballarat in 1855, and in 1857 the Ballarat Mining District was entirely changed by An Act for Amending the Laws Relating to the Goldfields (21 Vic.,No.32), commonly referred to the Goldfields Act of 1857. The Gold Commissioner system was entirely replaced by a system of Mining Boards, Mining Wardens, and their own Court of Mines, whereby miner’s had rights that otherwise would never have happened if it not for the diggers rising up against the corrupt colonial government. Eureka was the first crucial stepping-stone towards democracy in Australia.

Whilst I did not find any evidence of the Tinworth family’s direct involvement in the Eureka Stockade, they were most certainly affected by the aftermath of Eureka. After the Eureka Stockade, it was a time in Ballarat’s history where many of the diggers and local residents had regained their hope for a prosperous future, especially with the Geelong-Ballarat rail line opening up in 1862 allowing travel directly through to Melbourne, bringing a range of new industry to Ballarat.

By the 1860’s, the method of gold mining in Ballarat had shifted towards deep underground mining, whereby entire families would work the mine, sometimes with a number of employees to maximize productivity of each mine. The miners, particularly the owners, became quite wealthy and Ballarat was transformed from a tent city to an impressive opulent city in its own right. Many of the historic buildings of Ballarat were built from the profits of small to medium mining enterprises. However, it was not all gold and glory in the beginning, as the Tinworth’s quickly learned.

Tinworth Origins

Our main character, Charles Tinworth (~1832-1905), was born circa 1832 in a small rural village of Essex named Elmdon, which is about 100 kilometres north-northeast of London. His father was a butcher by the name of George Tinworth (1806-1851) and his mother was recorded as Mary Gamgee (1803-1890) also of Eldmon. George and Mary had nine children, seven of which emigrated to Australia. The three sons who stayed with their mother in Elmdon were John Tinworth (1828-1889), Abel Tinworth (1842-?) and Robert Tinworth (1844-1881).

Charles Tinworth is recorded at 19 years of age living with his family at 70 Ickleton Road, Elmdon, and worked as a butcher with his father.2 Soon after the 1851 census, his father passed away, which seemed to change Charles’ focus entirely. On 19 September 1853, Charles Tinworth married Elizabeth Ann Revel [Revill] (1828-1912) in the Saffron Walden Parish of Essex.3 Within a few months, we find Charles and Elizabeth Tinworth as passengers on the ship America as ‘assisted immigrants’ arriving in Geelong, Victoria, Australia, in May of 1854,4 only seven months prior to the Eureka Stockade.

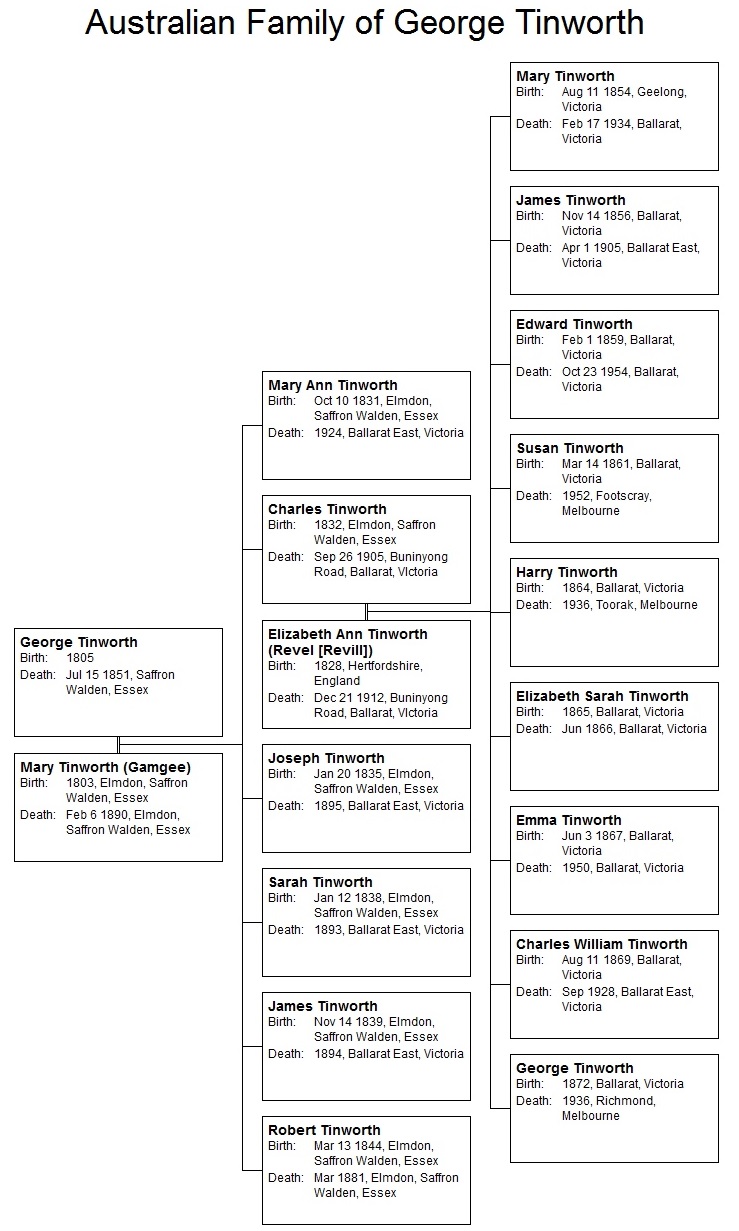

Charles must have settled first in Geelong, because their eldest daughter, Mary Tinworth, was born in Geelong on 11 August 1854. A family tree of George Tinworth’s children who emigrated to Australia is below, along with Charles’ nine children.

Figure 1 – Descendants of George Tinworth who emigrated to Australia, along with the nine children of Charles Tinworth. (Taken from birth, marriage and death records, all with further genealogical information from members of the Tinworth family)

There are few records of the Tinworth family in Ballarat prior to 1856 when James Tinworth was born, however this might be because the Ballarat Star was first published on 22 September 1855.5 The Ballarat Star was one of the main newspapers that recorded events and finds of miners. The Tinworths may well have moved to Ballarat after the Constitution of Victoria was enacted on 16 July 1855, because it allowed miners to vote and own land. However, we cannot rule the possibility that they were in Ballarat during the Eureka Stockade.

Arrival on the Goldfields of Ballarat

Two years before young Edward Tinworth passed away in 1954, his friend Henry Stackpoole recorded an interview with Edward for the Ballarat Historical Society on 13th May 1952. Edward told how times were very tough when he was a boy. So much so that both James, Edward and a number of his brothers and sisters were born in a tent on the hillside of Canadian Gully, just below Sovereign Hill. Canadian Gully was the main tented area for Canadians and those who didn’t necessarily agree with the Irish diggers camped on Bakery Hill. In 1952, Edward described the tent site as the present position of the Mount Pleasant School “plantation”.6

During the gold rush, the goldfields of Ballarat were over-run with thousands of diggers, all seeking their own fortune. They camped close together and many even shared meals around the campfire at night. Others would drink all night long, which of course, many times ended in brawls. There were drunken quarrels and fistfights, mainly recorded amongst the Irish, although I tend to think the media demonized the Irish. Whilst the diggers sat around the fire as mates, when it came to gold, nobody could be trusted. The goldfields were full of thieves, as the Tinworths discovered firsthand.

Canadian Gully is where the 6th largest gold nugget in the world was found on 31 January 1853, weighing in at 2,520oz – “The Canadian” nugget. Whilst some say Canadian Gully was named after the Canadian digger named Henry Ross after his involvement in Eureka, this cannot be the case, because “The Canadian” nugget was found over 12 months earlier. Just over a week before “The Canadian” was found, “The Sarah Sands”, the 8th largest nugget in Victoria, was found on 20 January 1853, weighing in at 1,117oz. Another “un-named” nugget was found only 2 days later, weighing 1,011oz.

John Thomas Dalton also found “The Lady Hotham Nugget” on 8 September 1854 in close proximity to Canadian Gully, weighing in at 1,177oz. It is the 7th largest nugget. The area was named “Dalton’s Flat” after John Thomas Dalton. This was followed by the “Welcome” nugget in 1858 that was found on Bakery Hill, Ballarat, weighing in at 2,217. This nugget remains the 3rd largest in the world. It happens to be where the diggers stood to make their stand in a massive meeting against the colonial government 4 years earlier. These five “big nuggets” set Ballarat firmly in the history books, which resulted in diggers flocking in from all over the world.

Optimism to Insolvency

Many a man sunk their life’s savings into travelling to the Victorian Goldfields, only to find their hopes dashed. Life was hard, the work even harder, and sickness was rife on the goldfields because of the difficult living conditions. By 1865, we find Elizabeth Tinworth had been ill for

around 18 months, and Charles had not succeeded in finding his fortune on the goldfields of Ballarat, so he headed to New Zealand, leaving his wife and family on the goldfields.

Edward Tinworth admitted in the early days many of the areas mined were barren and the Tinworth mining operations experienced low yields. With Charles’ losses in New Zealand, he was declared insolvent on 28 July 1865 and bankrupted for debts of £107.4.9 (107 pound, 4 shillings, and 9 pence). To put this in perspective, the average wage for a miner in Ballarat in June 1865 was 45 shillings for a 12 hour shift,7 which equates to about 13p 10s per week, based upon a six day working week. Thus, Charles Tinworth was bankrupted for around 8 weeks pay, which seems rather extreme. However, I tend to think there is more to this story.

On 12 June 1865, Charles first appeared in the Geelong District Court. Charles signed the following petition that was read out to the court:

To the honourable the judges of the supreme court of the colony of Victoria

The petition of Charles Tinworth of Ballarat East in

The colony of Victoria miner

Sheweth

That your Petitioner by misfortune and without any fraud or dishonesty on his part hath become Insolvent wherefore he is desirous of surrendering his Estate for the benefit of his creditors according to law and he hereby surrenders the said estate and prays that the same may be placed under sequestration and in proof of the matters aforesaid your petitioner has annexed hereto a true inventory and statement on oath of his whole estates and effects and the debts claims and liabilities affecting the same to the best of his knowledge and belief and an affidavit of the causes which have led to his insolvency.

Charles Tinworth- his mark

Dated at Ballarat, In the colony of Victoria this twelth Day of June In the year of our lord one thousand eight Hundred and sixty five…

The following list of creditors was proven, and un-disputed by Charles Tinworth:

Charles allegedly had an account at the grocer, butcher and baker, and had outstanding accumulated debt over a four year period (1862, 1863, 1864, 1865) before he was finally declared bankrupt. It is highly unusual for any debt to get beyond 90 days without being put on ‘stop credit’, even less in the 19th century. The wages due to John Stanbury, miner, were even more interesting, because the average wage for a miner in 1865 was 13p 10s per week, based upon a six day working week.8 The amount claimed of 9p 2s was allegedly over a two year period from 1862 to 1863. This does not add up, because it totals less than a week’s wages.

The other interesting fact is: his two brothers were included amongst the creditors; James for £10 and Joseph for £5. This seems like a token amount, almost as if they wanted to be included as creditors so that they could attend the creditor meetings, which would have otherwise been privy. John Stanbury may have been a stooge just in case the Tinworth brother’s claims were rejected. Charles may well have declared himself bankrupt for a reason. Could there have been a future claim that he was avoiding by being bankrupted, which could not proceed once he was declared bankrupt? The fact that Edward Tinworth admitted the Tinworth mining operations were managed by Charles Tinworth in a “patriarchal management” style, would suggest this bankruptcy was carefully orchestrated.9

I don’t think we will ever understand the complexities of why Charles went bankrupt. Could it have been just a matter of failed enterprises? In light of the Tinworth’s rebound during Charles’ bankruptcy period, which was nothing short of remarkable, I tend to think it wasn’t that simple. Edward Tinworth admitted that the family “pledged never to divulge any information to outsiders”,10 therefore, we must conclude the reasons will remain buried with the Tinworths.

Manslaughter

By 1868, during Charles’ bankruptcy period, the Tinworth’s were operating a mining company known as Perseverance Alluvial Company (also recognized as the Perseverance Company) where the three brothers, Charles, Joseph and James Tinworth, along with their friend Andrew Baxter mined in close proximity to the original gold mine of John Thomas Dalton on Dalton’s Flat. Some Chinese diggers were stealing up to £20 worth of gold per week from their puddling machine, and the brothers decided to stay up during the night and watch their claim in turns. It is interesting to note that the Tinworth’s still retained their mining tools and machinery during Charles’ bankruptcy, obviously transferred to his brother’s names prior. Charles’ assets were valued at a measly £8, yet the Tinworth’s mining asserts were worth considerably more.

On Friday 23 October 1868, James Tinworth shot and killed a Chinese Creswick digger recently out of Pentridge Prison, named Leong Mak How known as “the gambler”, while trying to steal gold from the puddling machine. After an inquest that day, Tinworth was committed to stand trial for manslaughter. The Ballarat Star recorded the entire incident on Saturday 24 October 1868, as follows:

Some excitement was caused on the morning on Friday morning when it became known that a Chinese, about to rob a claim, had been shot by James Tinworth, one of the shareholders, whose turn it was to watch the claim. The claim is situated at Dalton’s Flat, Ballarat East, and is about eighty yards distant northerly from the old police station on the Plank road. The claim, worked by a party of four men only in the day time, three of whom are brothers, has been in paying ground for some time past and is known as the Perseverance Alluvial Company. Within the last few weeks gold has been several times abstracted from their puddling machine, James Tinworth saying as much as £20 worth within a week. At length it was arranged by the partners to watch the claim in turns; and a small building erected close to the shaft, and within six or seven from the puddling machine, served as a hiding place for the watcher. About one o’clock in the morning of Friday, the watch, James Tinworth, according to his own statement, perceived two Chinese coming to the puddling machine; they had no business near the claim, it being forty yards at least from any footpath, a small track for the use of the claim only leading to it. The deceased passed close to the hiding place of the watch to reach the machine, armed with a stick such as is used by Chinese In carrying vegetables, some five to six feet in length. On being challenged he attempted to escape, and the night being dark, and fearing they both would succeed in evading him, he fired, and the deceased fell, the shot (No. 1) lodging in his face. He never moved, and the watch awoke his brother, who immediately started for the Ballarat East Police Station and acquainted them with the mishap. The deceased was a very muscular man, thirty years of age, and well known to the police.

On Friday afternoon the district coroner held an inquest at the North British hotel, Plank road, to enquire into the death of Leong Mak How, who was shot in the morning whilst attempting to rob the claim of the Perseverance Company, Dalton’s Flat. The following jury were sworn:- Joel Bushby (foreman), Joseph Chatterley, Wm. Grain, Geo. Dibdin, John Cuthbertson, Andrew Downes, Fred. Collins, Jas. Shaw, Jas. Dye, Chas. Taylor, Thos. Putt, Wm. Medder. Mr M’Dermott appeared to watch the case for the accused.

Joseph Tinworth deposed—I am a miner, and a shareholder in the Perseverance Company. The prisoner is my brother. He called me about two o’clock this morning and said two men were at the puddling-machine, and that he had fired at one of them and wounded him, and wanted me to come down and see. I went, and found a Chinaman bleeding. My brother Charles and the prisoner were present. The deceased was lying on his face. I then went for the police in company with a mate, Andrew Baxter. On returning an hour after, the body was still lying there. My brother (the prisoner) was on duty as watch last night. We took it in turns, having previously lost gold, certainly twice the last fortnight. We watched every night. I saw the pistol produced, both before and after the arrival of the police. I loaded the pistol with powder and No. 1 shot three nights before. My brother Charles had the pistol in his turn, as well as myself. My brother ran after the Chinese and tried to arrest him, and fired at him, having called upon him to stop. He told me so. The night was dark. My brother himself suggested sending for the police.

Charles Tinworth deposed—I am brother to the prisoner and reside with him. About one o’clock this morning my brother called me and said there were two men at the puddling machine, and that he had shot at them. I waited till the police came about three o’clock. No one touched the body. My brother said he first saw the Chinese coming from near the stable. The deceased went on his hands and knees to the puddling machine after crossing the whim ring. He passed very near to him, within four feet. He called to know what he did there. The deceased ran and my brother fired. I know the pistol produced, and have had it in my possession when watching.

Senior-constable O’Neill deposed—-In consequence of information received, I this morning went to a claim at Dalton’s Flat. On reaching there I found the deceased lying on his face, grasping the stick produced. The body was lying 62 feet from the machine—it was warm, but the hands were cold. Saw seven small wounds on the left side of the face and neck. Went to a small shed and found the pistol. The prisoner told me it was the pistol, and I cautioned him. He said they had lost within a week £20 worth of gold. The prisoner told me that at about one o’clock in the morning two men came to the machine, and that the deceased passed within four feet of him. On searching the body of deceased I found a piece of cloth with some matches, lottery tickets, and other trifling articles.

Hugh Ah Konn, publican, of Golden Point, deposed—I know the deceased, who lived with two or three others at Golden Point. He was called the ” Gambler,” and was knocking about. He had been discharged from Pentridge some six or seven weeks. I have known him mine at Creswick, but he was turned out for some offence; I think it was for spurious gold. I knew the deceased as Leong Ah How.

James Sutherland, M.D., deposed—I was called at half-past four o’clock this morning by the police, who told me a man had been shot. On examining the body, lying at the rear of the North British hotel, I found seven small wounds on the face and a contused wound on the forehead. I assisted Dr. Butler in making a post mortem examination. On examining the brain I found a large effusion of blood and serum on the brain. We considered the cause of death to be sanguineous apoplexy, caused by the wound on the forehead.

Geo. T. C. Butler, M.D., deposed—I examined the body and found seven shot wounds on the face and neck, and a contused wound on the forehead. None of the shot had penetrated the skull, but were deeply-seated in the muscles of the face. I found much extravasated blood at the base of the brain, at least three or four ounces. The cause of death was pressure on the brain, caused by falling on his forehead, but I could not say whether the fall was occasioned by the shot or not.

The coroner then carefully and minutely explained to the jury the differences between murder, manslaughter, and justifiable homicide, and left it to the jury to decide as to their verdict. After about three quarters of an hour, the jury decided on the following verdict:—The deceased’s death took place on the 23rd instant, on Dalton’s Flat, Ballarat East, and was caused by “extravasation of blood on the brain, arising from a fall on his forehead whilst running away from the puddling-machine of the Perseverance Gold Mining Company, and being fired at by James Tinworth on same day and at same place.”11

This was no doubt a heart wrenching time for the Tinworth family, especially James. The fear of spending 10 to15 years in Old Melbourne Gaol would have frightened young James beyond measure. We know from Carboni’s account that the prisoners of Eureka were held there in deplorable conditions for months. They were given nothing more than a board and a blanket to sleep on a cold damp slate floor with dozens of people crammed together like animals.

The conditions were so reprehensible that many men would rather take their own lives than be confined in such debased conditions. The screaming, shrieking and sobbing at night would send any sane man senseless. For this the gaoler had a special treatment – an iron mask and thick leather gloves, supposedly to stop the prisoner harming themselves. The food, if you can call it that, was a watery swill of dried maize with half a dozen grains of rice and the odd weevil or grub for added protein of course. If they were fortunate enough, every so often they would receive a slice of old sour mouldy bread to soak up the swill.12

Fortunately for James Tinworth, he was acquitted on 19 February 1869. One thing that came out of the trial of James Tinworth is the fact that they had established their name around Ballarat as diggers who would defend their claim unto death – nobody would ever dare steal from them again!

Rags to Riches

By 1871, the Tinworth family of gold miners also held title over a tenement on Madman’s Flat, Mount Clear (South of Dalton’s Flat), which was first surveyed on 10 August 1871 with the notation as being owned “under instrument 702 by Tinworth & Co.”13 Edward recorded that Charles had three shares and his two sons James and Edward each had one share.14 According to Edward Tinworth, a lad of twelve years discovered “The Indicator” – rich patches of gold filled flat quartz veins in the Prince Regent and Candanian Gully.15 That twelve year old lad was Edward Tinworth, or Ted as he was fondly called.

The plans developed by Edward Tinworth were so successful that after the few years, Charles’ trusted Edward so emphatically that he relied entirely upon Edward’s sole judgement, and Charles never ventured underground again. You could say that Edward possessed a God-given gift for gold prospecting. This is only seen in a handful of people around the world. They have an innate talent for seeking out gold, just as certain people were gifted to seek out truffles in Gloucestershire, England. Another example is water diviners, who seek out underground water and springs just by observing the land. I am not referring to those who claim to be water diviners by divination or hydromancy, but those who have a natural gift at a young age, like Edward Tinworth. Many tried to copy these gifted gold prospector’s practices over the years, but failed miserably.

Their first nuggety gold leader was found in around 1870 on the northern side of the crosscourse. Whilst a number of their nuggets were disclosed to the media and the Victorian Government, many were kept a secret. In June of 1880, the Tinworth’s dug up a large nugget of 250 ounces, as confirmed in the List of Nuggets of Victoria, verified by a W.Baragwanath with the remark “from The Indicator”.16 In today’s terms, this find would nett around $440,000, depending upon the purity.

A family could have retired on this find, and the Tinworth’s listed the mine for sale at £10,000. As there were no offers, the Tinworth family pushed on.17 So much so that they were sued in the Mining Court by Woah Hawp Company in 1883 for encroaching on the White Horse Ranges, whereby the arbitrator awarded damages of £218 plus costs.18 This is an interesting ruling considering a report by the Mining Surveyor confirmed the Prince Regent Company were trying to sink their mine to the depth of the Tinworth mine, and only 50 feet away:

The Prince Regent Company (formerly known as the Corn Exchange No. 2), situate at Sailors’ Gully, on the course of the Indicator and Woah Hawp Canton reefs, have completed the erection of a 20 horse-power engine capable of winding to 1,000 feet. The shaft has been timbered to a depth of 320 feet, and it is proposed to sink an additional 60 feet in order to strike the rich stone now being raised by Tinworth and Co., about 50 feet from the company’s shaft. The last crushing yielded over 1oz. to the ton, and the shareholders are hopeful of success. It is known that there is an extensive area of auriferous country still undeveloped extending in a southerly direction towards the Buninyong Estate, which, if proved, would afford employment to hundreds of miners.19

The Tinworth brothers were clearly ground breakers in the Ballarat mining community and other mining companies were trying to emulate their practices. Why? Simply because they produced the goods. An interesting article is found in the Evening News at Sydney relating to rumours of an “extraordinary find” of rich quartz in The Indicator on the White Horse Ranges just south of Ballarat on Friday 30 September 1881. The new article claimed the Tinworth’s yielded 996oz of pure gold, worth around $1.6M AUD today.20

This rumour was investigated by the Mining Department and reporters from the Ballarat Star. Both parties found it to be false, hence it is not listed in the nuggets of Victoria. There is an article in the Ballarat Star on Saturday 1 October 1881 below that confirmed a find of 83 pounds weight of gold yield over a two week period ending 30 September 1881 (the same date of the Sydney article), which resulted in 80oz of pure gold bar once melted.21 There is a note that this find was “far below that of the two previous terms (finds)”.

However, based upon Edward Tinworth’s assertions that Charles Tinworth believed “in the wisdom of keeping the results of his operations a close secret”, demanding his sons “pledge never to divulge any information to outsider’s”, would suggest that the family did not divulge the real amount of the find to the media or the government.22 After what happened to John Dalton and the Lady Hotham Nugget, this pact seemed very wise indeed.23 It is plausible to suggest that information of this find may have been withheld by the Tinworths.

Only two years later, on Monday 6 August 1883, the Tinworth family hit the jackpot again extracting gold nuggets amounting to 250 ounces, of which 130 ounces was expected to be pure gold. In today’s terms, this is a find of around $232,000. The Age Newspaper in Melbourne called them the “Lucky Diggers at Ballarat” in the following excerpt of 8 August 1883:

Messrs. Tinworth and party, of the Perseverance claim, White Horse Ranges, to-day exhibited at tho Corner another rich find of gold. The total weight of the specimens was 250 oz., about 130 oz. of which is expected to be pure gold. The specimens were obtained in the claim on Monday. This rich mine belongs to, and is worked by, a cooperative party of five, viz., Mr. Tinworth, his three sons and a Mr. Batton. It is stated that the party intend to put their mine upon the market. The gold was taken from the Indicator reef, which runs through the area of the mine, sand is worked at a depth of 300 feet.24

This afforded each brother opulent properties. On 15 November 1897, Edward Tinworth (1859-1954) was cited as owning a residence near Canadian Creek. The residence was recorded as 150 feet by 290 feet (about 1 acre) off Larter Street between Burden & Gale Street, Ballarat East.25

Electoral Roll records of 1903 show both Charles William Tinworth (1869-1928) and George Tinworth (1872-1935) were both “miners”, whereas their elder brother Edward Tinworth (1859-1954?) is recorded as a “mine owner” living with his wife Agnes at Geelong Road, Ballarat East.26 Charles’ eldest son James Tinworth was also recorded two years later in 1905 as a “miner” with his wife Elizabeth (nee Donavan) residing at 41 Clayton Street, Ballarat East, overlooking Canadian Creek.27 It is clear the Tinworth family were very successful in their mining enterprises, which is reflected in their property portfolios.

Interestingly, Edward Tinworth recorded a 350 ounce gold nugget in 1889, but this nugget never reached the newspapers or the government; news of it was not mentioned outside of the family circle, which suggests rumours of a large find in 1881 may well have been true. The Tinworths became quite affluent, as demonstrated by Charles’ list of properties in his Will, such as the famous British Queen Hotel. This hotel is mentioned in a number of early documents, especially being investigated by the Ballarat Licencing Court in 1888 along with a number of other licenced premises and was deemed the best accommodation in Ballarat with 19 rooms.

The proceeding in the Ballarat Licencing Court was printed in the Argus on Saturday 30 June 1888. Thus, the British Queen Hotel retained its licence, whereas many other were forced to close (45 of the 72 investigated), some quite notable historic hotels, such as the Eureka, Red Bull, Beehive, Golden Point and Plank Hill hotels. The British Queen Hotel was located at Main Road, Ballarat (later Bridge Street after major flooding and redirection of roads). They surrendered their Victuallers Licence on 13 August 1956 to be effective from 31 December

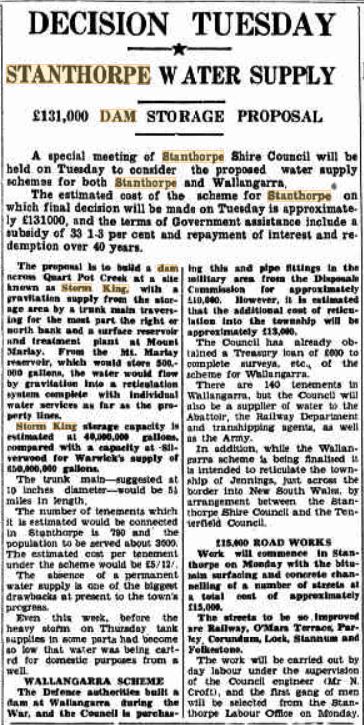

1956.28 Thus, the hotel closed on 31 December 1956. The property may well have been resumed. Only title searching or historic mapping will tell precisely. One comical media report is recorded about a man stealing potatoes, and another where it was used for a conference for the establishment of a High Court of the Ancient Order of Foresters on 11-12 May 1864 (links provided below).29

Then there is the commercial shop known as “Kings” on Main Road, Ballarat East housing “William Brother’s shop”, but there is only one building still standing from that era around that land size for the property specified. It is unoccupied and has no reference to “Kings” on the parapet. There was also farming land on Buninyong Road. This may be found on early maps or title searches for those wishing to research further. A property at 41 Clayton Street, Ballarat East was mentioned. This was Charles own home overlooking Canadian Creek. Existing numbering shows 41 Clayton Street is now parkland. There is no evidence of any properties in that street dating prior to 1905, therefore I assume it was resumed sometime later for parkland. Early title records would confirm this.

Charles’ Will contains a further property on Buninyong-Geelong Road – his final home. The actual number on the road is unknown, however there is mining lot on the same road north of the Church Reserve in Buninyong, south of Mount Clear. It is adjacent the Church to the north. Three doors up at number 1169 there is a house that could date to that era. Once again titles searches would confirm whether this is correct or not.

By 1915, we find Charles Tinworth (1869-1928), Louisa Tinworth (1891-1923), Elizabeth Tinworth, along with Revel Tinworth (1892-1975), son of Charles and Louisa Tinworth, all residing at Mount Clear. Charles Tinworth (Jnr) is recorded as a “miner” and Revel Tinworth is recorded as an “assayer” – a gold mining analyst.30 Revel was an Associate Metallurgist specializing in the area of gold analysis with the Ballarat School of Mines before he went into military service during World War II from 1939-48.31 He moved to 109 Cowles Road, Mosman NSW (another opulent Bungalow that still stands today) with his wife Ethol, where he became a Chemist and Assayer with the Burma Miners and Railway Company for the rest of his career.32

Thus, the entire Tinworth family were gold mine owners, diggers in their own right, and mining analysts for most of their natural lives. The majority of the family worked on the southern goldfields of Ballarat and celebrated both the day-to-day struggles and triumphs of the Ballarat mining community. They were integral pillars of the mining community, and could be compared with, and probably surpass the Dalton family who I have spent years researching.

Tinworth Legacy

The Tinworth family left a mark upon Ballarat that can still be seen today. Tinworth Avenue, Mount Clear was named after the Tinworth family who lived and mined in that very location.33 The original “Tinworth’s Mine” is listed on the Victorian Heritage Database as a “Heritage Inventory Site”, 34 located just around the corner at 10 Woolshed Drive, Mount Clear.

This is in the same location as the Ballarat Mine that was restarted in 2011 by Castlemaine Goldfields Ltd and is currently producing approximately of 46,000 ounces of gold per annum,35 delivering $43.4 million worth of gold revenue in its first full year of operation.36

This should give us some indication of the income and wealth of the gold miners who were first involved in early deep undergrounding mining, such as Tinworth & Co. Like the miners today, they worked hard, played hard, and enjoyed a luxurious lifestyle.

______________________________________

© 2012-7 inclusive Dr Peter D Matthews. All rights reserved.

For further information about “Dalton’s Flat’ and the true events of Eureka, please read “Dalton’s Gold”. This book is available from my

publisher at http://bassano.com.au/shop/

1 Turner, Ian, (2002), Australian Dictionary of Biography: Lalor, Peter (1827–1889), National Centre of Biography, Australian National University, first published in hardcopy in Australian Dictionary of Biography, Volume 5, (MUP), 1974.

2 1851 Census records Tinworth family with George as head and Mary wife at 70 Main Street (70 Ickleton Road, Elmdon).

3 Marriage of Charles Tinworth and Mary Revel, 19 Sep 1853. Saffron Walden, Vol 4a, Page 691.

4 Assisted British Immigration Index: Charles & Elizabeth Tinworth, Amercia May 1854, Charles Age 20, Elizabeth Age 24, Master John Cardyne, Book 10, Page 239.

5 The Star (Ballarat, Vic: 1855-1924), http://trove.nla.gov.au/newspaper/title/189

6 Stacpoole, Henry James (1952), The Story of Edward Tinworth and the Tinworth Mine, Ballarat Historical Society, p3.

7 Buninyong Gold Mine, Ballarat, Heritage Database: Wages 1865, p2. http://vhd.heritagecouncil.vic.gov.au/places/11896/download-report

8 Buninyong Gold Mine, Ballarat, Heritage Database: Wages 1865, p2. http://vhd.heritagecouncil.vic.gov.au/places/11896/download-report

9 Stacpoole, Henry James (1952), The Story of Edward Tinworth and the Tinworth Mine, Ballarat Historical Society, p1.

10 Ibid, p4.

11 Ballarat Star, A Chinese Shot While Attempting to Rob a Puddling Machine, Saturday, 24 Oct 1868, p3. http://trove.nla.gov.au/newspaper/article/113848351?searchTerm=james%20tinworth%20manslaughter&searchLimits=

12 Carboni, Raffaello, (1855), The Eureka Stockade, reprint available from www.freeread.com.au/ebooks/e00015.txt

13 Public Records of Victoria, Mining Surveyor’s Surveys, Ballarat East Division, 1871,Tinworth & Co. – Madman’s Flat, VPRS 1019, p19.

14 Stacpoole, Henry James (1952), The Story of Edward Tinworth and the Tinworth Mine, Ballarat Historical Society, p4.

15 Ibid, p3.

16 Department of Mines, Victoria (1912), Memoirs of the Survey of Victoria, p12. http://geology.data.vic.gov.au/reports/memoirs/G2001_memoir-12_OCR.pdf

17 Stacpoole, Henry James (1952), The Story of Edward Tinworth and the Tinworth Mine, Ballarat Historical Society, p5.

18 Leader Newspaper, Saturday 10 March 1883: Ballarat, p15. http://trove.nla.gov.au/newspaper/article/197993422?searchTerm=tinworth%20ballarat&searchLimits=

19 Mining Surveyor’s and Registrars Reports, Quarter Ended 31st March 1884: Ballarat Mining District, p26. http://www.parliament.vic.gov.au/papers/govpub/VPARL1884No27.pdf

20 Evening News, Sydney, Friday 30 September 1881, p2. http://trove.nla.gov.au/newspaper/article/107227824?searchTerm=%22extraordinary%20tinworth%22~20&searchLimits=l-decade=188

21 Ballarat Star, Saturday 1 October 1881, p2. http://trove.nla.gov.au/newspaper/article/202593950?searchTerm=tinworth%20september%201881&searchLimits

22 Stacpoole, Henry James (1952), The Story of Edward Tinworth and the Tinworth Mine, Ballarat Historical Society, p4.

23 Matthews, Dr Peter D (2012), Dalton’s Gold, Bassano Publishing House, ISBN 9780987365200.

24 The Age Newspaper, Lucky Diggers at Ballarat, Wed 8 Aug 1883, p5. http://trove.nla.gov.au/newspaper/article/202602475?searchTerm=tinworth%20ballarat&searchLimits=

25 Mining VPRS to 1897: Miners Rights 1874-1885 Unit 1, Applications for Residence and Business Areas Nos 23106-23305 – 1897-1897, excel spreadsheet.

26 Australian Electoral Rolls 1903

27 Australian Electoral Rolls 1905

28 Victorian Licensing Court (1957), Report and Statement of Accounts 1957FY, p9. http://www.parliament.vic.gov.au/papers/govpub/VPARL1958-59No4.pdf

29 http://nla.gov.au/nla.obj-69403947/view#page/n2/mode/1up

https://news.google.com/newspapers?nid=1300&dat=19530820&id=BwhFAAAAIBAJ&sjid=TsMDAAAAIBAJ&pg=1638,6054644&hl=en

30 Australian Electoral Rolls 1915

31 Australian World War II Military Service Records, 1939-1945, Service number N458690.

32 Australian Electoral Rolls 1930-68. Also refer Ballarat School of Mines, Students’ Magazine, 1916.

33 City of Ballarat, Road & Open Space Historic Index, http://www.ballarat.vic.gov.au/media/2253695/roads_and_open_space_historical_index.pdf

34 Victorian Heritage Database Report, Timworth’s Mine – Heritage Listed Location. http://vhd.heritagecouncil.vic.gov.au/places/11964/download-report

35 Castlemaine Goldfields, Liongold Corp. http://www.liongoldcorp.com/operations/castlemaine-goldfields/

36 Henderson, Fiona (2013), $43.4 million produced at Ballarat Gold, The Courier 31 January 2013, http://www.thecourier.com.au/story/1269772/434-millon-produced-at-ballarat-gold/