DOI: 10.13140/RG.2.2.11765.09449 (Citation of this paper). To download a PDF copy of this paper, please click the download button below.

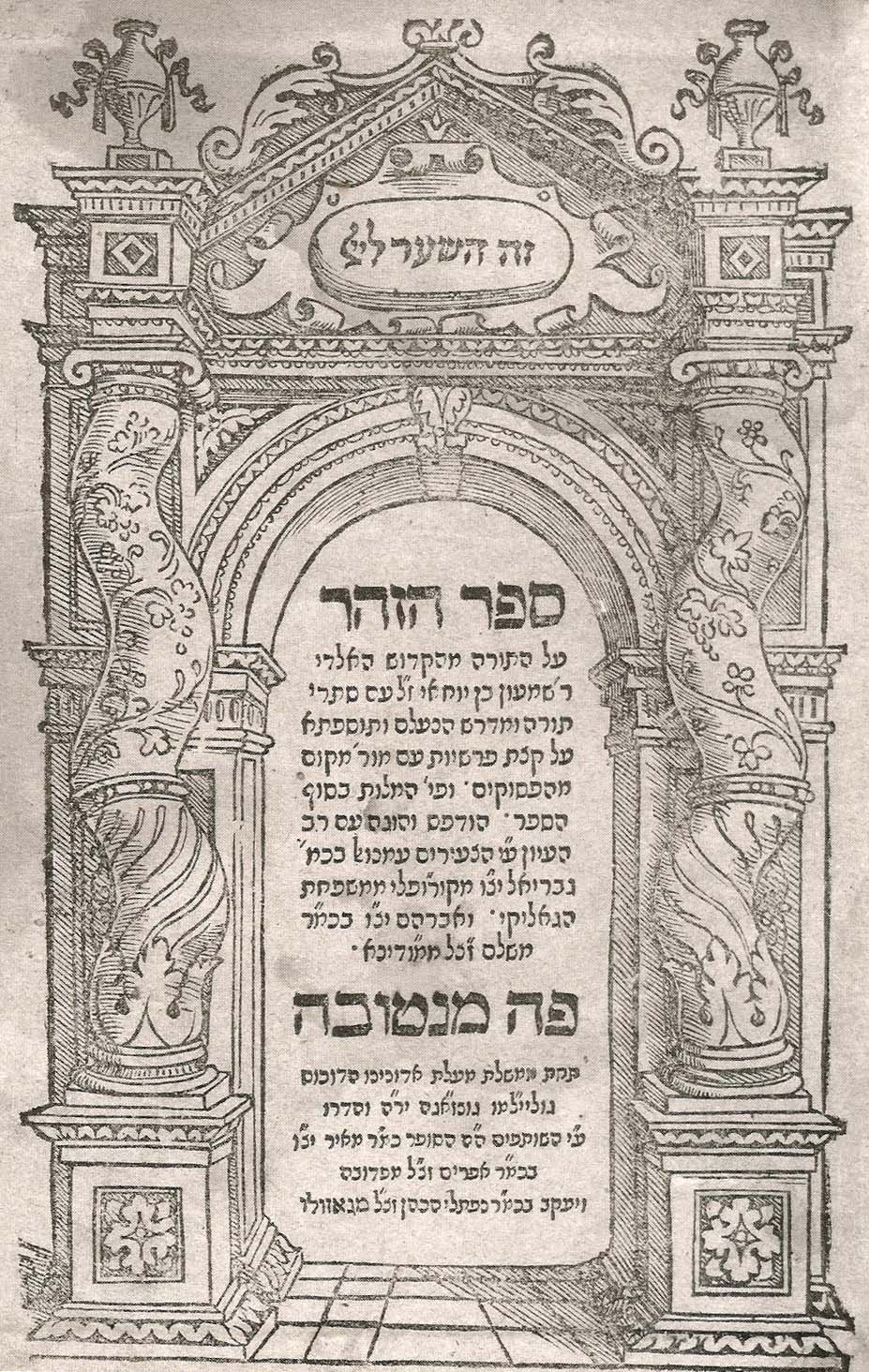

Most, if not all, scholars around the world, do not understand the different races and their imageries within the Shakespearean works. A young African-American woman named Katrina who is involved with Hollywood said to me in 2015, “You need to dig deeper” and those words lodged deep in my spirit. I spent the next six years travelling the world and examining thousands of historical documents before I found the actual source documents used by the Jewish poet Emilia Bassano, and late last year I managed to finish Tome 1 of my series ‘A Comprehensive Commentary of SHAKE-SPEARES SONNETS’ that I started over 15 years ago. One of the primary sources of the Shakespearean works is the Mantuan 1558-60 Aramaic and Hebrew Sefer ha-Zohar al ha-Torah (Book of Zohar, on the Torah) literally meaning, “Radiance on the Torah” (the Zohar), where the printing was supervised by Rabbi Isaac Bassano.[1] This paper is dedicated to Katrina…

Today, I wish to discuss the “mixed multitude”. Jewish Kabbalists would know these imageries from the Zohar as the רַ֖ב עֵ֥רֶב (erev rav, “mixed multitude”)that I briefly mentioned in Tome 1 of my series ‘A Comprehensive Commentary of SHAKE-SPEARES SONNETS’ from the verse: “And a mixed multitude also went up with them, along with great droves of livestock, both flocks and herds” (Exodus 12:38), upon exodus from Egypt.[2] Who are the mixed multitude? Zohar 2:192b explains the “mixed multitude” are the לּוּדִים (Ludim, Lydians,[3] noted as Egyptian descendants of Mizraim in 1 Chronicles 1:11, descendants of Ham in 1 Chronicles 1:8); וְכוּשִׁים (“and Kushim”, dark-skinned Cushites found in the Horn of Africa (Djibouti, Eritrea, Ethiopia, Somalia), the Nile Valley (Sudan and Egypt), and Great Lakes (Tanzania and Kenya), meaning descendants of Cush, a son of Ham in 1 Chronicles 1:8;[4] וְכַפְתּוֹרִים (“and Kaftorim”, Caphtorites, also descendants of Mizraim living by the Nile in 1 Chronicles 1:12),[5] and וְתוּגַרְמִים (Togarmans, descendants of Japheth in modern-day Turkey, in 1 Chronicles 1:5-6), with מְכַשְּׁפִ֑ים (sorcerers) meaning: “all of the sorcerers of Egypt” ― united together as one group, with one language, they are called רַ֖ב עֵ֥רֶב (erev rav, “a mixed multitude”), a group of deceiving sorcerers and soothsayers, who tried to deceive the Israelites.[6]

The Mixed Multitude

Now before I go any further, I must state this is not a racist slur in the Zohar ― far from it! Some scholars assert they were simply the Egyptian sorcerers sent to spy on the Israelites, but this is not the case. Some scholars assert they were the riff-raff ― the slaves held by Egypt, those in the Egyptians jails, and mercenaries who intermarried Israel,[7] but this is not strictly correct either. The Israelites did not intermarry out of their own race unless they were commanded by God, such as Hosea, who was commanded to, “Go and marry a prostitute, so that some of her children will be conceived in prostitution. This will illustrate how Israel has acted like a prostitute by turning against YHVH and worshiping other gods” (Hosea 1:2).[8] Israel was likened to a promiscuous woman when they sinned, by worshipping other gods. Many scholars claimed the promiscuous imageries in the Sonnets were about Emilia Bassano, but in fact, they were imageries about the Assembly of Israel at a certain period of time. It had absolutely nothing to do with the sexual chastity or otherwise of Emilia Bassano, thereby proving all these scholars merely defamed an innocent woman!

Today, we must be careful not to do the same. Not all Ethiopians are evil, just as not all Australians are evil. In Australia, there are quite a number of righteous people; there are some who like to call themselves bogans; some who are called riff-raff by others; and some are evil murders like John Bunting, Robert Wagner, and James Vlassakis, known today as the Snowtown murderers, who were convicted for murdering and dismembering paedophiles, homosexuals, and disabled people.[9] Thus, not all people are righteous, and not all are people are evil. In this case, the רַ֖ב עֵ֥רֶב (erev rav, “a mixed multitude”) refers to all those who were locked up in the jails of Egypt, for the day the Israelites departed Egypt, it was The Year of Jubilee,[10] where all the prisoners must go free ― thus Moses desired to bring each of them to salvation and sanctification of God, where everything is exposed in the light of God![11] It wasn’t about riff-raff or racism ― Rabbi Shim’on was teaching on The Year of Jubilee, and the opening of the 50th Gate of Binah during the Age of the Woman, which we entered on 29 November 2020 PST.[12]

Why did they follow Moses? Quite obviously the “mixed multitude” did not want to stay in bondage in Egypt, though the real reason is found in the wife of Moses, where it is recorded: “While they were at Hazeroth, Miriam and Aaron criticized Moses because he had married a Cushite woman” (Numbers 12:1). Here the word is cited as an הַכֻּשִׁ֖ית (a dark-skinned Cushite, or an Ethiopianess). The Bible also tells us, “it was Moses’ wife, Zipporah, took a flint knife and circumcised her son” (Exodus 4:25), and he was saved. It took a Woman named Zipporah to save the future of Israel. From that time onwards, those who preserved the Covenant and refrained from the sexual immorality seen amongst the Egyptians, Greeks, and Romans, were destined to become royalty — “Rex Judaeorum” ― a title later given to the Nasi family, who married into the Bassano family. Was Zipporah a Cushite? No, because we know she was the daughter of Jethro, the Midianite, who was the son of Reuel the Midianite (Numbers 10:29).[13] So who is this elusive Cushite? The answer is found in the 11th ― 14th centuries Midrash, Yalkut Shimoni on Torah (Gathering of Simon, on Torah) where in Shemot 168, Moses lived amongst the Cushites.[14] It was also recorded by Flavious Josephus, because nobody would go to war against them for fear of serpents, but Moses dared to do so. Princess Tharbis immediately fell in love with him at first sight:

Tharbis was the daughter of the King of the Ethiopians: she happened to see Moses, as he led the army near to the walls, and fought with great courage: and admiring the subtilty of his undertakings, and believing him to be the author of the Egyptian success, when they had before despaired of recovering their liberty; and to be the occasion of the great danger the Ethiopians were in, when they had before boasted of their great achievements, she fell deeply in love with him: and upon the prevalency of that passion, sent to him the most faithful of all her servants to discourse with him upon their marriage. He thereupon accepted the offer, on condition she would procure the delivering up of the city; and gave her the assurance of an oath to take her to his wife: and that when he had once taken possession of the city he would not break his oath to her. No sooner was the agreement made, but it took effect immediately: and when Moses had cut off the Ethiopians, he gave thanks to God, and consummated his marriage, and led the Egyptians back to their own land.[15]

The Hebrew Midrash, Yalkut Shimoni tells a different story, where Moses fled from Egypt to the land of Cush, and fought for the King, reconquering the city after he died, and took Queen Adonai as his wife (assumed mother of Tharbis), but did not consummate the marriage because of her idolatrous connections to the Dark Side.[1] Moses reigned for forty years and stepped down when her son Munchan, son of King Merops of Ethiopia, came of age.[2] There is another far greater citation of Moses and Queen Adonai, from the Hebrew Book of Jasher printed by Rabbi Meshullam Bassano in Venice 1625, son of Rabbi Isaac Bassano of Mantua, translated as follows:[3]

Moses, the son of Amram, was still king in the land of Cush in those days, and he prospered in his kingdom, and he conducted the government of the children of Cush in justice, in righteousness and integrity. And all the children of Cush loved Moses all the days that he reigned over them, and all the inhabitants of the land of Cush greatly feared him. And in the fortieth year of the reign of Moses over Cush, Moses was sitting on the royal throne whilst queen Adonai was before him, and all the nobles were sitting around him. And queen Adonai said before the king and the princes: What is this thing which you, the children of Cush, have done for such a long time? Surely you know that for the forty years this man has reigned over Cush he has not approached me, nor has he served the gods of the children of Cush. Now therefore hear, O ye children of Cush, and let this man no more reign over you as he is not of our flesh. Behold, my son Menacrus is grown up; let him reign over you, for it is better for you to serve the son of your lord, than to serve a stranger, a slave of the king of Egypt. And all the people and nobles of the children of Cush heard the words which queen Adonai had spoken in their ears. And all the people were preparing the accession until evening, and in the morning they rose up early and made Menacrus, son of Kikianus, king over them. And all the children of Cush would not dare to stretch forth their hand against Moses, for the Lord was with Moses, and the children of Cush remembered the oath which they swore unto Moses; therefore they did no harm to him. But instead the children of Cush gave many presents to Moses, and sent him from them with great honour. So Moses went forth from the land of Cush and went to find a home and ceased to reign over Cush. And Moses was sixty-six years old when he went out of the land of Cush, for the thing was from the Lord, for the period had arrived which he had appointed in the days of old, to bring forth Israel from the affliction of the children of Ham.

Book of Jasher 76:1-12.

This record changes the Jewish belief that Moses never consummated the marriage with Queen Adonai, where they claimed Moses was a great prophet of Israel who had to maintain the high standards of fidelity and connection to Shekhinah.[1] The Levites Miriam and Aaron, criticized Moses because: “he had married a Cushite woman” (Numbers 12:1), who made Moses King of the Cushites and saved all of her people from the hand of Pharoah. It is obvious that these people held a sweet place in God’s heart, despite them drawing from the left side. Aaron and Miriam could only see from the right side, because they were not close enough to Hashem to know the mind of God. Hashem did this to build the Tree of Life, for without the left side, we would not have procreation or music. This is explained further in my series of ‘A Comprehensive Commentary of SHAKE-SPEARES SONNETS’. Miriam was smitten with leprosy for 7 days for her comments, not for criticizing his Cushite wife, but for criticising Moses as God’s trusted servant, thus it was a warning to all of the camp that we must always be careful to not to criticize the Lord’s anointed (Numbers 12:10-15), because if we do, we will face judgement as a result.

Moses took the “mixed multitude” with him from Egypt because he was hoping to convert these people into his fold. The Cushites trusted Moses, because he was the former King of Ethiopia and “Rex Judaeorum” (King of the Jews). We learn later it is this “mixed multitude” that say, “Come, make us gods who will go before us” (Exodus 32:1), referring to the Golden Calf, drawing on the dark powers of Aries (Hebrew: טָלֶה taleh, 9+30+5=44), placing the Israelites back into bondage.[19] The key to all of the idolatry in Egypt by the “mixed multitude” and during the wilderness experience is this: the women of Israel refused to partake in any idolatry… It was only the men who listened to the lies of the mixed multitude.[20] Why? Because all women around the world are from Nukvah (the female aspect of God that pre-existed Elohim) connected to Malkhut (Shekhinah). Men are from Zeir Anpin (Short Face, Son), and were deceived by the mixed multitude’s story of Taurus (Golden Calf) conquering Aries (Lamb/Ram).[21] With this understanding, we can delve into the Shakespearean plays and examine why the Bassano family used the imageries.

Lydians

Let us begin with the לּוּדִים (Ludim, Lydians,[22] noted as Egyptian descendants of Mizraim in 1 Chronicles 1:11), who were later cited by Homer as Μαίονες (Lydians) as an ally of the Trojans, and died out during the Trojan War. They are not specifically cited in the Shakespearean works, but imageries to their music are often cited throughout the plays because they are origins to music.[23] The Lydian Omphale enslaves Heracles (Hercules).[24] The Bassano family, particularly Emilia Bassano, was fascinated by the power of the feminine Divine to conquer anything, especially “evil disposed men”,[25] just as the Romans and the Greeks.[26] Why were the Lydians wiped out during the Trojan War? One could argue it was their tomb of Alyattes, from donated monies by merchant-traders, craftsmen, and their practice of prostituting all the young women of Lydia before they could marry to collect a dowry, as recorded by Herodotus in The Histories 1:93-4 as follows:

In Lydia is the tomb of Alyattes, the father of Croesus, the base of which is made of great stones and the rest of it of mounded earth. It was built by the men of the market and the craftsmen and the prostitutes. There survived until my time five corner-stones set on the top of the tomb, and in these was cut the record of the work done by each group: and measurement showed that the prostitutes’ share of the work was the greatest. All the daughters of the common people of Lydia ply the trade of prostitutes, to collect dowries, until they can get themselves husbands; and they themselves offer themselves in marriage. The customs of the Lydians are like those of the Greeks, except that they make prostitutes of their female children.[27]

I had originally considered Hebbe Bassano might have been a Lydian, early in my research, because of the number of imageries used throughout the Shakespearean works by the Bassano family, however I now believe these are purely musical related. Many of the Bassano family members married Jewish partners wherever possible. Emilia was not a promiscuous woman; she was bashed and raped by a group of English noblemen,[28] then married Emilia off to the son of her first cousin, for good measure, though still of Jewish noble blood![29]

Cushites

The וְכוּשִׁים (“and Kushim”, dark-skinned Cushites) found in the Horn of Africa (Djibouti, Eritrea, Ethiopia, Somalia), the Nile Valley (Sudan and Egypt), and Great Lakes (Tanzania and Kenya), I will attempt to discuss as sensitively as possible, noting the Zohar was penned in the 2nd century AD by Rabbi Shim’on and printed by Rabbi Isaac Bassano in 1558-60.[30] The word וְכוּשִׁים is also used loosely to describe dark-skinned people of African origin during the 16th and 17th centuries, though they are separated by religion: African Muslims (who were called Blackamoors, even though they were not), African Christians, and African Israelites called Beta Israel (Ethiopian Jews), known as the descendants of King Solomon and the Queen of Sheba. This group of Beta Israel (Ethiopian Jews) were not part of the “mixed multitude” travelling alongside Israel in the wilderness, as they are future Jewish people. There are a number of African Jewry, including the Beta Israel, Yemenite Jews, Berber Jews ― many who have been subjected to investigation and confirmation of heraldry. There are also many African tribes desiring to associate themselves with Israel who have no Jewish heritage, and no evidence of historical compliance with Halakhah and other laws. These groups are called “the mixed multitude”, because they intend to deceive the Assembly of Israel, like some of those gathered at Mount Sinai. Therefore, the Zohar was not referring to the Christian or Jewish dark-skinned Cushites. The earliest account of an Ethiopian (Jew) who was converted to Christianity, was the treasurer of the Queen of Ethiopia being baptized by Philip the Evangelist (not Philip the Apostle), one of the seven deacons mentioned in Acts 8:26–27 as follows:

As for Philip, an angel of the Lord said to him, “Go south down the desert road that runs from Jerusalem to Gaza.” So he started out, and he met the treasurer of Ethiopia, a eunuch of great authority under the Kandake, the queen of Ethiopia. The eunuch had gone to Jerusalem to worship, and he was now returning. Seated in his carriage, he was reading aloud from the book of the prophet Isaiah (Acts 8:26-27).

There are only two references to an Ethiopian in the Shakespearean works. The first is where the Host of the Garter Inn says:

To see thee fight, to see thee foigne, to see thee

trauerse, to see thee heere, to see thee there, to see thee

passe thy puncto, thy stock, thy reuerse, thy distance, thy

montant: Is he dead, my Ethiopian? Is he dead, my Fran-

cisco? ha Bully? what saies my Esculapius? my Galien? my

heart of Elder? ha? is he dead bully-Stale? is he dead?[31]

Now this entry seems quite unusual, but it is a reference to the passage: “Can an Ethiopian change the color of his skin? Can a leopard take away its spots? Neither can you start doing good, for you have always done evil” (Jeremiah 13:23). This is a medieval concept of pondering what happens after death ― the very theme of SHAKE-SPEARES SONNETS. It is an imagery of Rabbi Isaac the Blind who describes the Torah as “black fire written on white fire” from the Midrash, where God showed Moses the Menorah made out of white, green, red and black fire.[32] When you turn on a light switch, you immediately dispel darkness, but then the poet goes one step further, and says “ha bully” (calling bullshit), asking the doctor “is he dead bully-Stale?” (stale urine, generally a horse), meaning when a person dies, their bodily fluids eventually begin to weep from every crevice. It was believed they enter Purgatory (a place of darkness without light – in torment), therefore, he cannot be surrounded by light (an imagery of the Menorah).

The second entry is in Act 4, Scene 4 of The Winter’s Tale:

Old Sir, I know

She prizes not such trifles as these are:

The gifts she lookes from me, are packt and lockt

Vp in my heart, which I haue giuen already,

But not deliuer’d. O heare me breath my life

Before this ancient Sir, whom (it should seeme)

Hath sometime lou’d: I take thy hand, this hand,

As soft as Doues-downe, and as white as it,

Or Ethyopians tooth, or the fan’d snow, that’s bolted

By th’ Northerne blasts, twice ore.

Ethiopians are of quite dark complexion, with gleaming white teeth. The latest census shows 43.4% of the population are Ethiopian Orthodox Christian 43.5%, Protestant 18.5%, Catholic 0.7%, Muslim 33.9%, traditional 2.7%, and other 0.6%.[33] In a study of contemporary North Ethiopian Orthodox Christian talismanic practices, Siena de Ménonville found they used the simple toothbrush to lure a suitor, that might surprise many people:

…he prepares a spell that is contained in—the toothbrush or the handshake—that will make the hopeful suitor attractive to his object of affection. The toothbrush leaves its magical properties on the suitor’s teeth, which will in turn enchant the intended recipient. The handshake is a medium of witchcraft that is found in other cultures contexts. Bonhomme (2012: 214) remarks upon the use of handshakes in penis snatching practices in Senegal: “The anonymous handshake, whose initiator is always the alleged penis snatcher, is perceived by the other party as a threatening gesture.” Jeanne Favret-Saada (1980: 114) also writes that handshakes are a trigger for witchcraft in that they are “such an ordinary gesture of recognition that one usually forgets what is involved”.[34]

There are volumes of Ethiopian talisman magic available in Britain since the 14th century, therefore they would have been available to Emilia Bassano, who wrote The Winter’s Tale, and is one of the characters.

Morocco

Morocco is the north-western region of North Africa, with Algeria, Libya and Egypt to the east. Officially they claim 99% Sunni Muslim religion, though Gallop International polls reported 93% in 2015.[35] There is only one play mentioning the Prince of Morocco, and this is The Merchant of Venice, a play about Antonio and Baptista Bassano, and their incredible bond as brothers. There are two usages of this word “Morocco”, excluding stage directions. The first entry from Act 1, Scene 2 as follows, by the servant of Portia:

The foure Strangers seeke you Madam to take

their leaue: and there is a fore-runner come from a fift,

the Prince of Moroco, who brings word the Prince his

Maister will be here to night.[36]

Here we find the servant of Portia is told that a “fore-runner” has come from a fift (fifth suitor), the Prince of Morocco, who brings news that the Prince (his Master) will be here tonight. Portia relies with: “If I could bid the fift welcome with so good heart as I can bid the other foure farewell, I should be glad of his approach: if he haue the condition of a Saint, and the complexion of a diuell, I had rather hee should shriue me then wiue me”.[37] This reply should have realized Portia desired a dark complexion, such as Baptista Bassano, and “the condition of a Saint”, meaning a Tzaddik (righteous man), a Levite who could make her shrive (be close enough to hear her confessions unto God), a Rabbi, a Pastor, a scholar, of which Baptista Bassano was a scholar.

Then we have the arrival of the Prince of Morocco, who brandishes familiar words from SHAKE-SPEARES SONNETS:

Mislike me not for my complexion,

The shadowed liuerie of the burnisht sunne,

To whom I am a neighbour, and neere bred.

Bring me the fairest creature North-ward borne,

Where Phoebus fire scarce thawes the ysicles,

And let vs make incision for your loue,

To proue whose blood is reddest, his or mine.

I tell thee Ladie this aspect of mine

Hath feard the valiant, (by my loue I sweare)

The best regarded Virgins of our Clyme

Haue lou’d it to: I would not change this hue,

Except to steale your thoughts my gentle Queene.[38]

The opening verses of “my complexion, the shadowed liuerie of the burnisht sunne” are also used in Sonnet 18 with the verse “And often is his gold complexion dimm’d” for the face of Elohim (Christ) and the study of Torah, and “burne the long liu’d Phaenix in her blood” referring to Shekhinah.[39] In Idra Rabba 3:129a, we find a description of Ze’eir Anpin with a forehead of “gold countenance” or “gold complexion”,[40] which is the Lesser Countenance of YHVH through Tif’eret (Christ). The outer face shines like “silver”, and the inner concealed Lesser Countenance is like “gold”, reflecting the countenance of Shekhinah — though further wisdom of the Divine faces can only be revealed to serious students and companions.[41] The countenance of Shekhinah can be likened to a beautiful dark woman like Naamah (whose name means “the beautiful”),[42] whereas Emilia wrote: “Be like faire Phoebe, who doth loue to grace the darkest night with her most beauteous face” speaking of (Malkhut) Skekhinah, the sun lighting the face of (Binah) Adonai, the moon, Night. We see the same imagery in Sonnet 127 with “blacke beauties” in “the ould age”,[43] referring to the time of Creation to the time of Solomon and the Shulamite.

Thus, we have the two different aspects of God, through Shekhinah, an imagery of the sun, and Adonai, an imagery of the Moon in the End of Days. It is the demonic aspect that will rise in the End of Days, that will try to “steale your thoughts my gentle Queene” ― it is Elohim’s seal that holds the impure forces back from until the final day comes, when He releases them for the final battle, and the eradication of evil. It is about the Prince, his Master Above coming, meaning Elohim Adonai, who will destroy all of Her enemies. The Bassano family prophesied, “who brings word the Prince his Maister will be here to night” meaning in this Era.[44] The interesting connection is his reply to Portia: “That slew the Sophie, and a Persian Prince that won three fields of Sultan Solyman, I would ore-stare the sternest eies that looke” for this is a reference to the Archangel Michael who slew these demonic strongholds. Michael is recognized in Jewish Kabbalah as Elohim, the chief angel guarding over Israel.[45] His purpose was to forewarn of what is to Come, just as the day of old! It is entirely prophetic. It was the Day of Rosh Hashanah (New Year and the Day of Judgement), where the Bene Elohim [Archangels, Bene ha-Elohim, Sons of Israel] convene the Jewish Beit Din (like a Sanhedrin, court). It was not about the Moroccan dynasties of Marinid and Saadi. We see this confirmed when he arrives at the caskets: “Some God direct my iudgement, let me see” then he surveys the inscriptions, meaning he performed the Jewish Hatarat Nedarim ceremony and renounce any vows made by accident during the year.[46] At this point, the Beit Din (Sanhedrin) was in session, for they weigh everything in the balance of scales. Whilst women do not normally do Hatarat Nedarim on the eve of Rosh Hashanah,[47] we find Portia had the inscriptions done by her father before passing, and the intention was to find her a suitable suitor, who could understand the Jewish inscriptions. Whilst this occurs below, the Sanhedrin sits Above, where Satan serves as the prosecutor in The Chamber of Judgement:[48]

And weigh thy value with an euen hand,

If thou beest rated by thy estimation

Thou doost deserue enough, and yet enough

May not extend so farre as to the Ladie:[49]

Scholars should have realized this was about the payment to avert judgement, for the verse tells that one: “must give, for what?” ….“Doe it in hope of fair advantages”.

Must giue, for what? for lead, hazard for lead?

This casket threatens men that hazard all

Doe it in hope of faire aduantages:[50]

Michael then considers whether they are deserving of judgement or not, whether weak, disabling (likening sickness to sin, like that of the Carrion), and that’s why the Lady needs to come ― to rid the world of sickness. They admit we deserve Her even at birth, because we are all sinners through Adam. Then they discuss the “evil impulse” which is a regular topic right throughout the Sonnets, involving the source of procreation, fortunes, passion (love), pondering, “What if I strai’d no farther?” wondering if they are too far gone…

And yet to be afeard of my deseruing,

Were but a weake disabling of my selfe.

As much as I deserue, why that’s the Lady.

1005I doe in birth deserue her, and in fortunes,

In graces, and in qualities of breeding:

But more then these, in loue I doe deserue.

What if I strai’d no farther, but chose here?[51]

He then moves onto gold, which I will not discuss in detail, only mention, “Let’s see once more this saying grau’d in gold. Who chooseth me shall gaine what many men desire” again referring to the evil impulse of men. He opens the casket and says, “O hell! what haue we here, a carrion death, within whose emptie eye there is a written scroule; Ile reade the writing.” I will not discuss the inscription here, because it is in my upcoming book, but this is an imagery of the Carrion Jews in Spain, not far from Belmonte de Miranda,[52] who were murdered, imprisoned, and their houses burned to the ground in 1109, after Alfonso VI died. Alfonso VII upon the advice his of Chamberlain, Yehosúa ben Yosef ibn Ezra Nasi, ordered equality between Christians and Jews. Yosef ibn Ezra Nasi was the direct ancestor of Yosef Nasi, who was the grandfather of both Rachel Nasi and Joseph Nasi, cousins of Elena Bassano (nee Nasi),[53] which suggests the play was penned by the first-generation Bassano-Nasi family. In Act 2, Scene 1 of Julius Ceasar, we find the Jewish Carrions mentioned again as:

Sweare Priests and Cowards, and men Cautelous

Old feeble Carrions, and such suffering Soules

That welcome wrongs: Vnto bad causes, sweare

Such Creatures as men doubt; but do not staine

The euen vertue of our Enterprize,

Nor th’insuppressiue Mettle of our Spirits,

To thinke, that or our Cause, or our Performance

Did neede an Oath.[54]

The Hebrew word הָרָחָֽ (Carrion) means: the dead, putrefying flesh of an animal, stinking whereby it is corrupted and non-kosher food. It is also used in relation to a person who is deceased and their carcases are left rotting, or a contemptable bird, animal, or person who would eat such carcasses as food (vulture, raven, magpie, etc.).[55] The biblical expositor Alexander Maclaren wrote of the condition of the carrion, as a blight upon society:

Are there no European societies at this day that in their godlessness and social iniquities are hurrying fast to the condition of carrion? Look around us — drunkenness, sensual immorality, commercial dishonesty, senseless luxury amongst the rich, heartless indifference to the wail of the poor, godlessness over all classes and ranks of the community. Surely, surely, if the body politic be not dead, it is sick nigh unto death. And I, for my part, have little hesitation in saying that as far as one can see, European society is driving as fast as it can, with its godlessness and immorality, to such another ‘day of the Lord’ as these words of my text suggest. Let us see to it that we do our little part to be the ‘salt of the earth’ which shall keep it from rotting, and so drive away the vultures of judgment.[56]

“Old feeble Carrions, and such suffering Soules that welcome wrongs” refers to those who died,[57] where if worthy, they ascend to the site of their rung (Tzaddikim, plural), where the body lies in peace resting on its couch, as it is written: “Then he enters into peace, and they’ll rest on his couches, each one living righteously” (Isaiah 57:2).[58] Zohar 1:123a tells us, “The soul goes to the Edenic site concealed for her”, where they are greeted by angels.[59] If they were not worthy and deserved punishment, they would wander around visiting the grave every day, like a “Merchant-trader” selling their wares to passers-by’s — in a promiscuous tone of prostituting themselves with the influence of Babylonian merchants (Ezekiel 16:29),[60] essentially like Carrions revisiting the dead carcass. It is a Jewish Kabbalistic expression for those not worthy of entering the afterlife. We find the last entry gives us the final clue: “Out vpon it old carrion, rebels it at these yeeres” referring to the resurrection of the dead at these [last] years.[61]

Blackamoors

The Moors are a paper entirely on their own, but I will mention a few verses from Othello and The Merchant of Venice. In Act 1, Scene 1 of Othello, we find the verse:

And I (blesse the marke) his Mooreships Auntient[62]

A number of scholars suggest Iago is mocking Othello by making a comment on his race,[63] but this is simply not the case. One must understand religion and theology to understand this verse. When Abram was ninety-nine years old, the LORD appeared to him and said, “I am El-Shaddai—‘God Almighty.’ Serve me faithfully and live a blameless life. I will make a covenant with you, by which I will guarantee to give you countless descendants” (Genesis 17:1-2).[64] The phrase “And I (blesse” is a sign of the covenant, which was recognized by “the mark” of circumcision of all descendants of Abraham, including Ishmael, for it is written: “Every male among you shall be circumcised. You are to undergo circumcision, and it will be the sign (mark) of the covenant between me and you” (Genesis 17:10-11).[65] The reference to his connection to his Moorship is a connection to Ishmael, where Abraham said to God, “May Ishmael live under your special blessing!” (Genesis 17:18), which is in fact ancient, assuming Aaron is a descendant of Ishmael. God replied:

“No—Sarah, your wife, will give birth to a son for you. You will name him Isaac, and I will confirm my covenant with him and his descendants as an everlasting covenant. As for Ishmael, I will bless him also, just as you have asked. I will make him extremely fruitful and multiply his descendants. He will become the father of twelve princes, and I will make him a great nation. But my covenant will be confirmed with Isaac, who will be born to you and Sarah about this time next year.” knowing the blessed lineage was through Isaac (Genesis 17:19-21).[66]

Zohar 1:119a explains, “The Ishmaelite are destined at that time (at the arrival of the Messiah) to incite all nations of the world to attack Jerusalem,”[67] as it is written: “I will gather all the nations to Jerusalem to fight against it; the city will be captured, the houses ransacked, and the women raped. Half of the city will go into exile, but the rest of the people will not be taken from the city” (Zechariah 14:2). After the radicals from the left and the right are destroyed, then and only then, the arousal of rejuvenation of the world will occur. This involves a mark upon the righteous to be spared, which is the full understanding of this verse. The radicals of the left are the terrorists who desire destruction and death, but there are also radicals of the right, who believe they are righteous when they are not – they are “like lukewarm water, neither hot nor cold, I will spit you out of my mouth!” (Revelation 3:16). We must walk the middle line of balance, known as Torah!

The next entry I want to discuss is in The Merchant of Venice, where Jessica threatens to tell her husband what they said, defending herself, and distinguishing herself from the Moors:

Nay, you need not feare vs Lorenzo, Launcelet

and I are out, he tells me flatly there is no mercy for mee

in heauen, because I am a Iewes daughter: and hee saies

you are no good member of the common wealth, for

in conuerting Iewes to Christians, you raise the price

of Porke.[68]

Here Jessica tells Lorenzo, Launcelot Gobbo, and the Clown that she is a Jew’s daughter, defending her faith, and Lorenzo replied, calling her a Moor, even though they knew she was a Jew:

I shall answere that better to the Common-

wealth, than you can the getting vp of the Negroes bel-

lie: the Moore is with childe by you Launcelet?[69]

The clown interjected, stating she is much more that a Moor:

It is much that the Moore should be more then

reason: but if she be lesse then an honest woman, shee is

indeed more then I tooke her for.[70]

This record shows that Jews in England may have been wrongly called Moors, simply because they were ignorant of dark-skinned European Jews, and mistook them for Blackamoors, which is a “member of the group of Muslim people from North Africa who ruled Spain from 711 to 1492”.[71]

During the 16th century and early 17th century, slavery of Blackamoors was a major problem, even from a young age. In Philip Sidney’s 1591 The Countess of Pembroke’s Arcadia, he tells the story of four Blackamoor boys mounted on each horse towing a coach:

And so getting on their horses, they travelled but a little way, when in opening of the mouth of the valley into a fair field, they met with a Coach drawn with four milk-white horses, furnished all in black, with a black-a-Moor-boy upon every horse, they all apparelled 30 in white, the Coach itself very richly furnished in black and white.[72]

We can conclude the Bassano family were not Blackamoors, because they would not have the finances, freedom, monopolies, and trust of several respective crowns being Blackamoors, who were expelled from Britain. The Bassano family were not expelled, although they were confused as Spaniards. I have written a paper titled, ‘Were the Bassanos Blackamoors, Black Hebrews, or tanned Italian-Spaniards?’ that addresses this aspect separately. It is available on my website.

Egyptians

There are four plays that mention the word “Egyptian” or “Egyptians” including: Antony & Cleopatra, Othello, Pericles, and Twelfth Night. We will begin with an interesting entry in Act 1, Scene 2 of Antony & Cleopatra:

Let him appeare:

These strong Egyptian Fetters I must breake,

Or loose my selfe in dotage.[73]

In the opening of Scene 2, a messenger comes to Antony to report that Fulvia and Lucius Antonius, had a change of heart and joined forces against Caesar. The Roman historian Suetonius recorded in The Lives of the Caesars, Augustus 14:1, “When Lucius Antonius at this juncture attempted a revolution, relying on his position as consul and his brother’s power, he forced him to take refuge in Perusia, and starved him into surrender, not, however, without great personal danger both before and during the war”.[74] Why “strong Egyptian Fetters I must breake, or loose my selfe in dotage (old and weak)?” The answer is found the knots. Israel was in bondage from crowns, powers, and most importantly incantations of letters and numbers with twisted cords with knots and accompanying amulets (adornments).[75] There were ten demonic crowns that were smashed by אלהים הוי״ה (HaVaYaH Elohim), which explains the verse: “Nor dare I question with my iealious thought, where you may be, or your affaires suppose” for it is written: “Do not worship any other god, for YHVH, whose name is Jealous, is a jealous God” (Exodus 34:14), as He does not tolerate adultery. Worship of false gods is regarded as adultery. With the three rungs of power, and the three knots, coupled with the adornments, Elohim (Christ) came to their rescue, for it is written: “et-Elohim heard their groaning, and et-Elohim remembered his covenant promise to Abraham, Isaac, and Jacob” (Exodus 2:24),[76] meaning in the Hebrew אֶת־ אֱלֹהִ֖ים (et-Elohim), drawing the Hebrew letters of Creation, thereby destroying the klipot, for they are brought to nought. The Hebrew letters hold creative power to crush the enemy, breaking the bondage of the Egyptians.

The second is a cunning slur against the Egyptian goddess Nephthys, known as “Mistress of the House”, with the phrase, “the Egyptian Bacchanals, and celebrate our drink”:

Ha my braue Emperour, shall we daunce now

the Egyptian Backenals, and celebrate our drinke?[77]

Nephthys is the Egyptian goddess of drunkenness, especially beerfests, and hangovers. Then they turn to wine, for the “Monarch of the vine” is Hashem, the God of Israel, for it is written: “Eat your food with joy, and drink your wine with a happy heart, for God approves of this! Wear fine clothes, with a splash of cologne! Live happily with the woman you love through all the meaningless days of life that God has given you under the sun” (Ecclesiastes 9:7-10). The deep mysteries of Kabbalah are described as the “sweet pomegranate wine” that we discuss throughout Sonnets 40 – 43, for it is written: “I would bring you to my childhood home, and there you would teach me. I would give you spiced wine to drink, my sweet pomegranate wine” (Song of Songs 8:2), for the wise who engage in Torah while they sleep at night and greet Shekhinah in the Upper Garden of Eden, basking in the blackness of the morning Rose.[78] It is not about Egypt; they compare the whoredom of Egypt to the sweetness of Israel.

I will conclude with a wonderful imagery from Act 4, Scene 2 of Twelfth Night:

Madman thou errest: I say there is no darknesse

but ignorance, in which thou art more puzel’d then the

Ægyptians in their fogge.[79]

This is a wonderful imagery of Pharoah in his own clouded judgement believing he is a god, being ignorant of the Face of בֹּ֖א (Bo), another Name for God. Pharaoh’s mistaken belief is expressed in the following passage: ‘“This is the finger of אֱלֹהִ֖ים (God, Christ)” the magicians exclaimed to Pharaoh. But Pharaoh’s heart remained hard. He wouldn’t listen to them, just as יְהוָֽה (YHVH, transposed as הוי״ה HaVaYaH) had predicted’ (Exodus 8:19).[80] What Pharaoh and his magicians did not understand is when the Name of הוי״ה אלהים (HaVaYaH Elohim) is called upon, the forces of evil are completely annihilated.[81] The Egyptian army died because of Pharoah’s “ignorance”, which the poet described as a “fog”.

___________________________________________________________

For further information on the Bassano family and their connection to the Shakespearean works, please read my major academic works of:

Books

- Shakespeare Exhumed: The Bassano Chronicles (2012)

- Genesis of the Shakespearean Works (2017)

- Tome 1 of A Comprehensive Commentary of SHAKE-SPEARES SONNETS (2020)

- Tome 3 of A Comprehensive Commentary of SHAKE-SPEARES SONNETS (expected 2021)

- Tome 2 of A Comprehensive Commentary of SHAKE-SPEARES SONNETS (expected 2022)

- Salve Deus Rex Judaeorum: Expositor’s Edition (Coming Soon)

Papers

- Understanding the Gender Complexities of Shakespeare

- New Research into the Bassano Instruments

- Were the Bassanos Blackamoors, Black Jews, or tanned Italian-Spaniards?

- Bassano’s 1710 Performance Invoking Angels Sparked Revival

- The ‘Early Plays’ of Shakespeare?

- The Bassanos: Jewish Guardians of the Ancient Arts

- Antonio Bassano’s 1544 Sefer ha-Refu’ot (Book of Remedies)

- Leather Cover of the Bodleian First Folio

- Early evidence of a female author in the First Folio

- Bassano Legal Case in Romeo and Juliet

- New Research into Shake-Speares Sonnets, proving Emilia Bassano-Lanier’s is the Poet

- New Research into Shake-Speares Sonnets – Dr Peter D Matthews has found the original sources

- The Just Men of England Live On

- We have Entered a New Prophetic Era

- Just Men and Just Women Understand the Nature of God

- The Just Men and Just Women Stand and Let Their Light Shine

- Earliest Version of ‘As You Like It’ may have been Venetian

- Understanding ‘The Mixed Multitude’ in the Shakespearean Works

You can like my Facebook page to keep abreast of any updated material. My academia profile is also available here.

[1] Matthews, Dr Peter D (2020), A Comprehensive Commentary of SHAKE-SPEARES SONNETS (Tome 1 of 3), Bassano Publishing House, Australia, ISBN: 9780992285791, p71.

[2] Exodus 12:38, ESV.

[3] Josephus, Flavius, Antiquities of the Jews, Book 1, Chapter 6.

[4] Acts 8:23; Goulbourne, Harry (2001), Who is a Cushi?, Race and Ethnicity: Solidarities and communities, New York: Routledge, ISBN 9780415224994.

[5] Josephus, Flavius, Antiquities of the Jews, Book 1, 4:2.

[6] Matt, Dr Daniel C. (2002-2014), The Zohar, Pritzker Edition, Stanford University Press, Section: Ki Tissa 2:191a in Vol 6, p79.

[7] Bar, S. (2008), Who Were the “Mixed Multitude?” Hebrew Studies, 49, 27-39. http://www.jstor.org/stable/27913875

[8] Hosea 1:2, NLT.

[9] Keane, Daniel; Martin Patrick (2019), Life after death: Dark tourism and the future of Snowtown. https://www.abc.net.au/news/2019-05-20/can-snowtown-ever-shake-off-its-dark-past/11082778?nw=0

[10] Zohar 2:45b; Matthews, Peter (1997), Living in the Year of Jubilee, Kingswood Press, ISBN 9780646349503.

[11] Luria, Rabbi ben Shlomo Ha’Levi; Vital, Rabbi Hayyim; Wisnefsky, Rabbi Moshe Yaakov (2006-19), Apples From the Orchard, Chabad House Publications, ISBN 9789659105410, pp. 330-1.

[12] Yardeni, Yael (2020), Astrological Secrets for the Kabbalistic Year to Come – 2021. https://kabbalah.com/en/online-courses/lessons/astrological-secrets-for-the-kabbalistic-year-to-come/

[13] Here Jethro is identified as Hobab in Numbers 10:29, Moses’ father-in-law.

[14] Yalkut Shimoni on Torah (Gathering of Simon, on Torah), Shemot 168.

[15] Josephus, Flavius, Antiquities of the Jews, Book 2, Chapter 10.

[16] Yalkut Shimoni on Torah (Gathering of Simon, on Torah), Shemot 168.

Ullman, Rabbi Yirmiyahu (2017), Moses, King of Cush. https://ohr.edu/7253

[17] Ibid.

[18] Rosenfeld, Rabbi Dovid (2021), Moses’s Cushite Wife. https://www.aish.com/atr/Moses-Cushite-Wife.html

[19] Matthews, Dr Peter D (2020), A Comprehensive Commentary of SHAKE-SPEARES SONNETS (Tome 2 of 3), Bassano Publishing House, Australia, ISBN: 9780992461652, p67.

[20] Luria, Rabbi ben Shlomo Ha’Levi; Vital, Rabbi Hayyim; Wisnefsky, Rabbi Moshe Yaakov (2006-19), Apples From the Orchard, Chabad House Publications, ISBN 9789659105410, pp. 51-2.

[21] Ibid.

[22] Josephus, Flavius, Antiquities of the Jews, Book 1, Chapter 6.

[23] Matthews, Dr Peter D (2017), Genesis of the Shakespearean Works, Bassano Publishing House, ISBN 9780992461607.

[24] Soph., Trach. 247ff.

[25] Lanier (Bassano), Emilia (1611), Salve Deus Rex Judaeorum (Hail God, King of the Jews), Salve, 615-6, 1529-36.

[26] Hall, Edith (1989), Inventing the Barbarian: Greek self-definition through Tragedy, Oxford, p95.

[27] Herodotus, with an English translation by A. D. Godley (1920), The Histories, Harvard University Press, 1:93-4. http://data.perseus.org/citations/urn:cts:greekLit:tlg0016.tlg001.perseus-eng1:1.93

[28] Bassano, Emilia (1594), Willobie His Avisa.

[29] Emilia was the daughter of Baptista Bassano. Alfonso Lanier was the son of Nicholas Lanier (1544-1611) and Lucretia Bassano (1565-1616), daughter of Antonio Bassano, Emilia’s first cousin.

[30] Matthews, Dr Peter D (2020), A Comprehensive Commentary of SHAKE-SPEARES SONNETS (Tome 1 of 3), Bassano Publishing House, Australia, ISBN: 9780992285791, pp. 1-9.

[31] F1, Wiv 2.3.1088-93.

[32] Matthews, Dr Peter D (2020), A Comprehensive Commentary of SHAKE-SPEARES SONNETS (Tome 1 of 3), Bassano Publishing House, Australia, ISBN: 9780992285791, p120.

[33] Ethiopia: Religion. https://culturalatlas.sbs.com.au/ethiopian-culture/ethiopian-culture-religion

[34] Ménonville, Siena de (2018), Approaching the Debtera in Context: Socially Reprehensible Emotions and Talismanic Treatment in Contemporary Northern Ethiopia. https://journals.openedition.org/etudesafricaines/22890?lang=en

[35] Gallop International (2015), Losing Our Religion? Two Thirds of People Still Claim to Be Religious. https://www.gallup-international.bg/en/33531/losing-our-religion-two-thirds-of-people-still-claim-to-be-religious/

[36] F1, MV 1.2.314-7.

[37] F1, MV 1.2.318-22.

[38] F1, MV 2.1.518-29.

[39] Q1, Son 18.261.

[40] Zohar 3:129(a).

[41] Zohar 1:9(a).

[42] The Pulpit Commentary: Genesis 4:22, Electronic Database. (2001-2010), BibleSoft Inc. https://biblehub.com/commentaries/pulpit/genesis/4.htm

[43] Q1, Son 127.1892-3.

[44] F1, MV 1.2.316-7.

[45] Matthews, Dr Peter D (2020), A Comprehensive Commentary of SHAKE-SPEARES SONNETS (Tome 1 of 3), Bassano Publishing House, Australia, ISBN: 9780992285791, pp. 244-52.

[46] F1, MV 2.7.986-7.

[47] Posner, Menachem (2017), What Is a Beit Din? https://www.chabad.org/library/article_cdo/aid/3582308/jewish/What-Is-a-Beit-Din.htm

[48] Matthews, Dr Peter D (2020), A Comprehensive Commentary of SHAKE-SPEARES SONNETS (Tome 2 of 3), Bassano Publishing House, Australia, ISBN: 9780992461652, p29.

[49] F1, MV 2.7.998-1001.

[50] F1, MV 2.7.990-2.

[51] F1, MV 2.7.1002-8.

[52]Matthews, Dr Peter D (2013), Shakespeare Exhumed: The Bassano Chronicles, Bassano Publishing House, Australia, ISBN 9780987365255, pp. 223-224.

[53] Matthews, Dr Peter D (2013), Shakespeare Exhumed: The Bassano Chronicles, Bassano Publishing House, Australia, ISBN 9780987365255, pp. 223-224.

[54] F1, JC 2.1.760-7.

[55] Webster’s Revised Unabridged Dictionary: Carrion.

[56] Maclaren, Alexander (1903), The Carrion and the Vultures. https://ccel.org/ccel/maclaren/matt2.iii.xix.html

[57] F1, JC 2.1.761-2.

[58] Isaiah 57:2, International Standard Version.

Wolski, Dr Nathan (2016), The Zohar, Pritzker Edition, Stanford University Press, Section: Midrash Ha-Ne’lam, Sarah 1:122(b) in Vol 10, p370.

[59] Matthews, Dr Peter D (2013), Shakespeare Exhumed: The Bassano Chronicles, Bassano Publishing House, Australia, ISBN 9780987365255, p324.

[60] Ibid.

[61] F1, MV 3.1.1250.

[62] F1, Oth 1.1.35.

[63] de Silva, Sharya (2008), And I – God bless the mark! – his Moorship’s ancient.” Othello, I.I, line 32. http://english142b.blogspot.com/2008/05/and-i-god-bless-mark-his-moorships.html

[64] Genesis 17:1-2, NLT.

[65] Genesis 17:10-11, NLT.

[66] Genesis 17:19-21, NLT.

[67] Matt, Dr Daniel C. (2002-2014), The Zohar, Pritzker Edition, Stanford University Press, Section: Va-Yera 1:119a in Vol 2, p190.

[68] F1, MV 3.5.1842-7.

[69] F1, MV 3.5.1848-50.

[70] Ibid, 1851-3.

[71] Matthews, Dr Peter D (2020), A Comprehensive Commentary of SHAKE-SPEARES SONNETS (Tome 1 of 3), Bassano Publishing House, Australia, ISBN: 9780992285791, p33.

[72] Sidney, Philip (1591), The Countess of Pembroke’s Arcadia, Lib I, line 25-30, p37.

[73] F1, Ant 1.2.208-10.

[74] Suetonius: The Lives of the Caesars, The Life of Augustus, 14:1. https://penelope.uchicago.edu/Thayer/E/Roman/Texts/Suetonius/12Caesars/Augustus*.html

[75] Gandz, Solomon (1930), The Knot in Hebrew Literature, or from the Knot to the Alphabet, Isis, 14(1), 189-214. Retrieved 2020. http://www.jstor.org/stable/224386

[76] Exodus 3:24, NLT; Zohar 2:38a.

[77] F1, Ant 2.7.1543-4.

[78] Wolski, Dr Nathan (2016), The Zohar, Pritzker Edition, Stanford University Press, Section: Midrash Ha-Ne’lam, Zohar Hadash: Va-Yetse ZH28a-b in Vol 10, pp. 435-6.

[79] F1, TN 4.2.2028-30.

[80] Exodus 8:19, NLT.

[81] Luria, Rabbi ben Shlomo Ha’Levi; Vital, Rabbi Hayyim; Wisnefsky, Rabbi Moshe Yaakov (2006-19), Apples From the Orchard, Chabad House Publications, ISBN 9789659105410, pp. 301-2.