To download a copy of this academic paper in pdf format, please click here: PAPER – Understanding the Gender Complexities of Shakespeare

Introduction

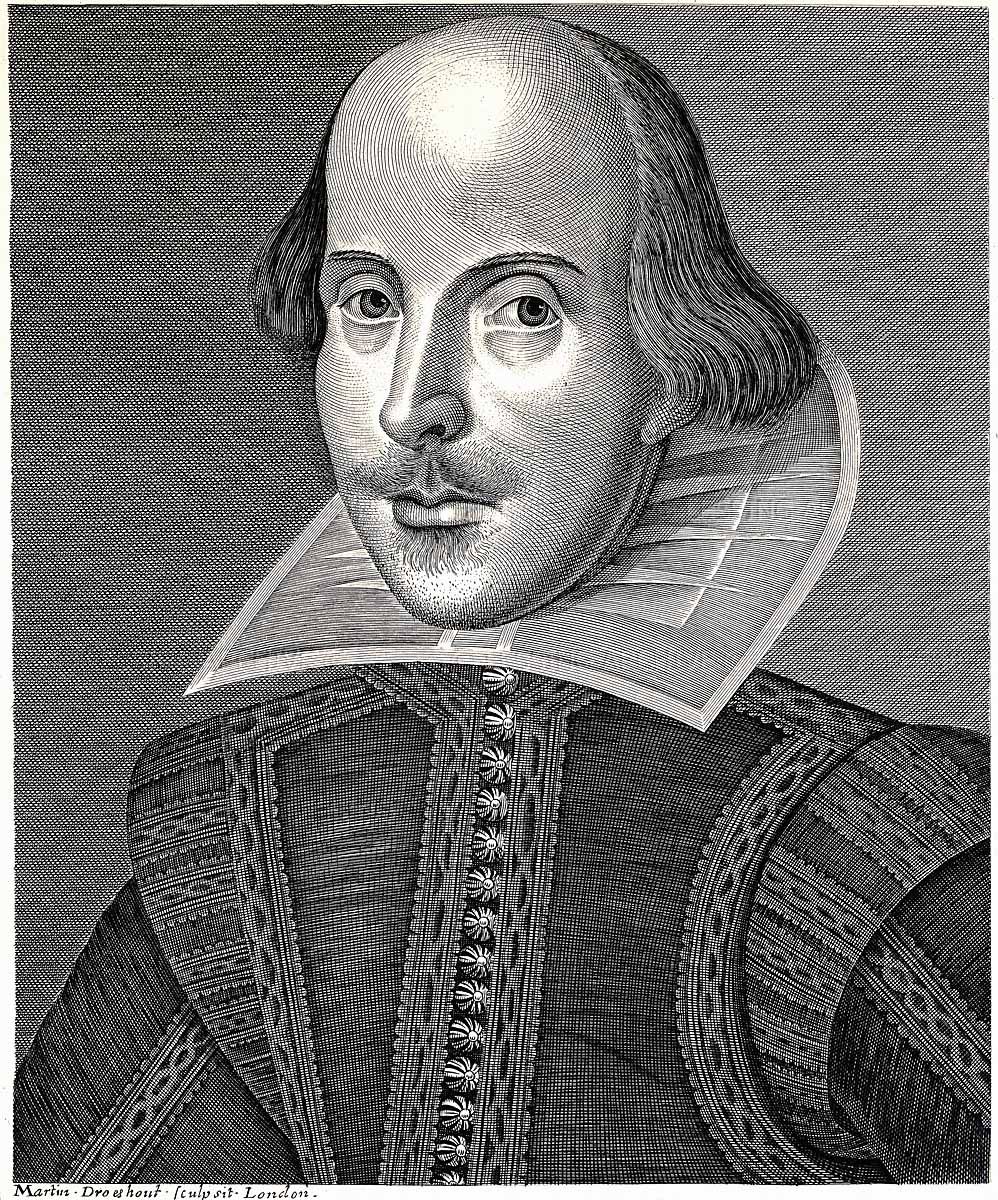

The dramatists of Shakespeare are often characterized as being feminists because of the frankness of Cordelia in King Lear, the shrewdness of Portia in The Merchant of Venice, and the psychological manipulation of Volumnia in Coriolanus. For over four hundred years we have performed the incredible representations of men and women and their various roles and responsibilities in society during the latter Renaissance period, where male actors would have pretended to be the character of Viola in Twelfth Night, while pretending to be her brother Sebastian, as a male character. This seems to be quite a complex idea in the latter sixteenth century. Some scholars have suggested that feminism did not exist during this era. I will prove in this paper that these assertions are fatally flawed – feminism was alive and well during that era. However, the dramatists of Shakespeare were not feminists, per say, they were in fact Master Kabbalists teaching the gender complexities of the ancient Zohar and the Tree of Life, where one can allow ego to ruin one’s life, or shut down our reactive system and be transformed to the supernal realm of perfection beyond human perception and repair the world.

Historical Background

With the humanist movements in Europe, particularly Italy, during the 15th and 16th centuries many women rose to study philosophy of women and positions of power. One such document was the ‘Querelle des Femmes’ (The Woman Question) that began a movement circa 1500, followed by a lectured on the ‘Virtues of the Female Sex’ by the learned philosopher Heinrich Agrippa of Nettesheim in 1509. An Italian author Baldassare Castiglione then published a book titled ‘The Book of the Courtier’ in 1528 based upon Agrippa’s lecture. The first wife of King Henry VIII, Catherine of Aragon, had ‘Instruction of a Christian Woman’ (1523) translated for her daughter Mary I, so the topic was certainly discussed and debated in England.[1] Then we had John Knox opposing this movement allegedly because of his interpretation of the bible:

For who can denie but it repugneth to nature, that the blind shal be appointed to leade and conduct such as do see? That the weake, the sicke, and impotent persones shall norishe and kepe the hole and strong, and finallie, that the foolishe, madde and phrenetike shal gouerne the discrete, and giue counsel to such as be sober of mind? And such be al women, compared vnto man in bearing of authoritie. For their sight in ciuile regiment, is but blindnes: their strength, weaknes: their counsel, foolishenes: and judgement, phrenesie, if it be rightlie considered.[2]

Then we had Stephen Gosson attacking the women attending the plays “that which I have gathered by [personal] observation” having spent considerable time “in narrowe lanes then in large fields” of London, observing these plays being performed firsthand his observation of women during these performances:

In our assemblies at playes in London, you shall see suche heauing, and shoouing, suche ytching and shouldring, too sitte by women; Suche care for their garments, that they bee not trode on: Such eyes to their lappes, that no chippes light in them: Such pillowes to ther backes, that they take no hurte: Such masking in their eares, I knowe not what: Such giuing the Pippins (tart) to passe the time: Suche playing at foot Saunt without Cardes: Such ticking, such toying, such smiling, such winking, and such manning them home, when the sportes are ended, that it is a right Comedie, to marke their behauiour, to watche their conceites, as the Catte for the Mouse, and as good as a course at the game it selfe, to dogge them a little, or followe aloofe by the print of their feete, and so discouer by slotte where the Deare taketh soyle.[3]

For centuries scholars have not realized that Gosson had “found the schoole, and reade the first lecture of all my selfe” aluding to his own involvement during times when Oxford when closed for break prior to his graduation in 1576. Having dated Schoole of Abuse in 1576, Stephen Gosson attacked and criticized many of the Shakespearean plays being performed down narrow lanes, then in large fields. He cited direct and indirect quotes from most of the “Early Plays”.

Both Knox and Gosson cited above wrote of women as foolish and childish, yet the dramatists of Shakespeare would disagree completely. We have Portia (Katherine Bassano, nee Fieschi) who is neither a fool nor child; she is a rich, beautiful, fearless woman who defeated Shylock in his own game of chess, by dressing as a male barrister in the Venetian court. It is in part a true story about Antonio Bassano, the Merchant of Venice, and his brother Baptista (Bassinio) Bassano and his rich noble heiress wife of the Fieschi family. They descend from the Ravaschieri Princes of Belmonte, which explains the connections in the play. Antonio was a real merchant in Venice before and after moving to London. Their London merchant business operated for many generations.

Philosophical Motivation of the Dramatists

To understand the complexities of these characters and why they used gender changes in their work, we need to understand their philosophical motivation behind these ideals before we can begin to fathom their precepts. Women in England were oppressed for centuries. The bible clearly teaches equality between husband and wife, not domination over the weak and forced submission as depicted and taught by John Knox and others.

The use of the caskets and Bassanio choosing lead is a Jewish precept. Meanwhile Antonio was locked up in jail in Venice awaiting his trial, with Shylock demanding his pound of flesh, citing his bond. After Bassanio left, Portia came up with an idea to go to Venice disguised as men. Portia turns to her servant Balthasar and asks her to go to her cousin in Padua, Dr Bellario (also a real Dr Hieronymus Benalius, who lived in Anotnio Bassano’s mansion), with a letter and bring the notes and garments he would give. Bassanio arrived and offered six thousand ducats for the three thousand loaned; yet Shylock was not interested in money, but in teaching Antonio the lesson of his life. Seeing the merciless Shylock, the Doge decided to step in:

Vpon my power I may dismisse this Court,

Vnlesse Bellario a learned Doctor,

Whom I haue sent for to determine this,

Come heere to day.[4]

The clerk of the court read the letter from Dr Bellario confirming the doctor was very ill, but instead sent a young judge in his place named Balthasar, who was actually Portia in disguise as a man. Portia entered a theological yet legal debate regarding the law and justice, enthusing Shylock to prepare the knife to cut a pound of flesh from Antonio’s bosom, as he refused up to ten times the amount due by Bassanio. Antonio said his last goodbyes to Bassanio in preparation to meet his maker, and in return Bassanio assured he would give up the wife he loved and sacrifice everything for him.

Portia paused the proceeding on a precept of law of Venice prevented the shedding of Christian blood, therefore determined that if Shylock shed but one drop, all of his possessions would be confiscated by the state of Venice. Shylock faltered, requesting to just take his principal of 3,000 ducats and go. Portia insisted that he must forfeit his principal. Shylock was insulted by Portia’s comments and decided he would simply leave. Portia then threw her fatal blow asserting that he had enacted the law of Venice to take the life of a citizen, which by law requires half of his assets to the state, half to the defendant, and he should beg for mercy before the Doge for his very own life.

In my latest major academic work of ‘Genesis of the Shakespearean Works’ I proved that many of the Shakespearean plays were penned and performed on London streets long before William Shakespeare was born, and all of those plays were embellished with Hebrew piyyut (embellished poetry used as poetic song in worship on Sabbaths and festivals),[5] Jewish (particularly Essene) theology, and Kabbalistic lore from the Sefer Yetzirah, the Babylonian Talmud, and the first Zohar of Mantua. In fact, a play written as a book by Hieronymus Bassano as a “comedy written in the vernacular of free will”, which was banned by the Catholic Church is likely to be the earliest version of ‘As You Like It’ – a Hebrew phrase of the ‘appointed time’ from Ecclesiastes 3:1-8 and Daniel 7:25 in relation to the festive season, where one has the freedom to do what you like (free will). All of Hieronymus de Bassanus’ (Jeronimo Bassano) Jewish books of plays, remedies, and Kabbalah were banned under the Index Librorum Prohibitorum of 1559. I proved that the wider Bassano family were Rabbis and Jewish Master Kabbalists who were responsible for the printing of the Zohar of Mantua in 1557 and the expounded version of 1558-60, and the Bassano family of England taught Kabbalah amongst the English.

Furthermore, The Bassano family used their plays, books, music and musical instruments to teach the English people the ancient philosophy of Kabbalah. However, they clearly opposed the masonic philosophy no different to Rabbi Solomon Bar Isaac (1040-1105) (Rashi), who in his prophetic piyut (poem) Selikhot attacked the Templar Knights as sun worshippers. In 2 Henry IV penned prior to 1576 while Shakespeare was just a boy, the Bassano’s referred to Masonry as a seductress (Lilith, Succubus) who would thrust the Entered Apprentice into substantial moral decline. This understanding is necessary as we investigate the gender complexities of their works, including the Shakespearean plays, their Zoharic texts, Antonio Bassano’s 1544 ‘Sefer ha-Refu’ot’ (Book of Remedies), Emilia Bassano’s 1611 Salve Deus Rex Iudæorum (Hail God, King of the Jews). The Bassano’s were not Pharisees, nor Sadducees, but they were Jewish Essenes – much of their teaching can be directly correlated with many of the ancient Essene texts, the Dead Sea Scrolls, and the Zoharic texts that were otherwise inaccessible during that era. With this understanding, we can now explore the gender complexities of their work.

Gender Complexities Through the Eyes of a Master Kabbalist

Within the Kabbalistic view of creation, the Zohar teaches a precept on gender that when masculine powers of the serifot reach Shekhinah, She is transformed from masculine מָה (Mah) to feminine םי (Mi). As the ritual goes, the letter ה (he) departs and the י (yod) enters, and She adorns herself in masculine clothing in the presence of every single male in Israel. Other letters Israel draws from above to this site: אֵלֶּה (Elleh). She then rules the world. You might find this a little deep but hang in there for my explanation of the text. Zohar 1:2a states that:

Rabbi Shim’on said, “So the heavens and their array were created by מָה (Mah), What, as it is written: When I behold your heavens, the work of Your fingers, the moon and stars that You set in place,… מָה (Mah), (how) majestic is Your name throughout the earth! Your splendour is celebrated above earth (Psalms 8:4, 1). Above heaven, to attain the name. For it created a light for its light., one enclothed in the other, and it attained a high name. So, In the beginning, Elohim created (Genesis 1:1) Eholim above. For מָה (Mah) was not so, is not composed until these letters – (Elleh – These I remember) – are drawn from above to below and Mother lends Daughter Her garments, though not adorning Her with Her adornments. When does She adorn Her fittingly? When all males appear before Her, as it is written: [All your males shall appear] before the Sovereign, YHVH (Exodus 23:17). This one is called Sovereign, as is said: Behold, the ark of the covenant, Sovereign of all the earth (Joshua 3:11). Then the letter ה (he) departs and the י (yod) enters, and She adorns herself in masculine clothing in the presence of every single male in Israel. Other letters Israel draws from above to this site: אֵלֶּה (Elleh), These I remember (Psalms 42:5). ‘With my mouth I mentioned them, in my yearning I poured out my tears, drawing forth these letters. Then I conduct them from above to the house of Elohim, to be Elohim, like Him’. With what? With joyous shouts of praise, the festive throng.”[6]

Firstly, you probably noticed the Mother lends the Daughter Her garments, and when all males appear before Her, She adorns herself in masculine clothing in the presence of every single male in Israel. Whilst this does speak of Elohim (God of all gods) in creation, it also has a practical application in Judaism, and it has a major Kabbalistic significance and application to the play of The Merchant of Venice. Let us first establish the significance to Judaism. All Israelite males are commanded to appear in God’s Temple in Jerusalem three times a year on the pilgrimage festivals: Pesah (Passover), Shavu’ot (Festival of Weeks) or The Giving of the Torah, and Sukkot (Festival of Booths) also known as Feast of Tabernacles.[7]

Yet there is a spiritual meaning that is linked to the human ritual below that stimulates the serifot above in the heavenlies. As the ritual goes, the letter ה (he) departs and the י (yod) enters, and She adorns herself in masculine clothing in the presence of every single male in Israel. Other letters Israel draws from above to this site: אֵלֶּה (Elleh). With the arrival of the letters, Shekhinah also attains the name Elohim, plus Elleh.[8] The verse describes both the earthly pilgrimage to the Temple and the divine procession of emanation to Shekhinah. We must understand that Shekhinah is the feminine divine manifest presence of God. In the Mishnah, Tractate Megillah 29A indicates that the Shekhinah ‘went with the Jewish people wherever they were exiled’[9] and even ‘earthquakes were used as signs of her presence’.[10] The verse in the Zohar teaches that the physical and spiritual are linked whereby as the precession to the Temple, how I walked with the crowd, conducted them to the house of Elohim, with joyous shouts of praise, the festive throng.[11]

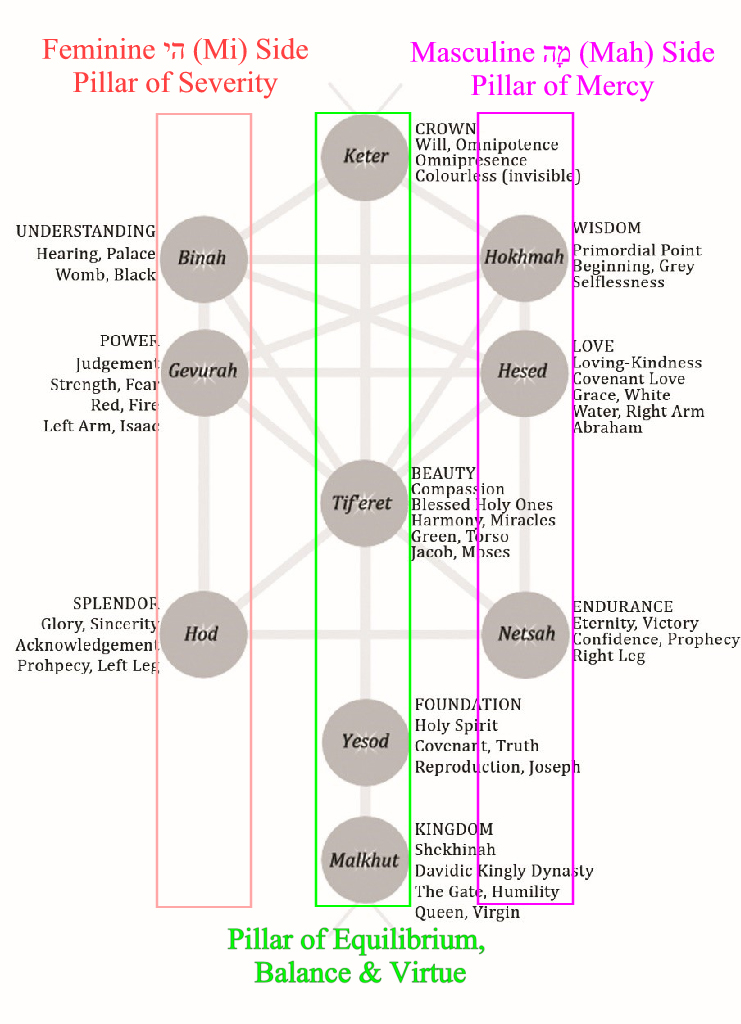

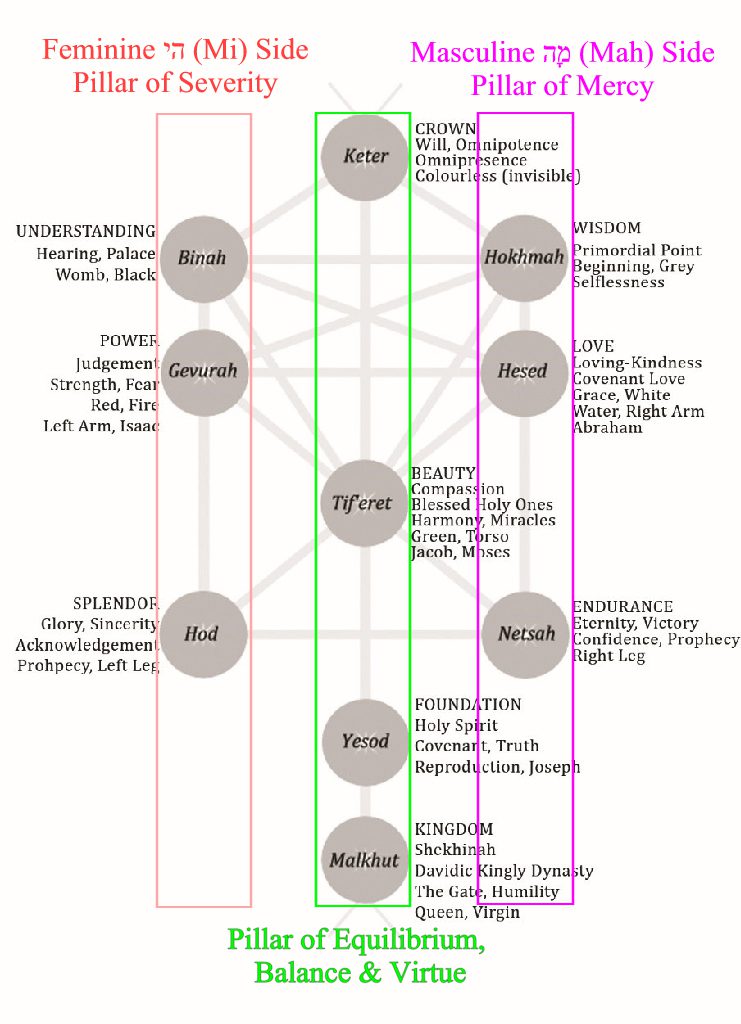

We must also understand the Tree of Life to understand the letters from masculine מָה (Mah) to feminine םי (Mi). Overleaf is an image taken from my book ‘Genesis of the Shakespearean Works’ of the Tree of Life. According to the Zohar, there are ten sefirot or emanations in the Tree of Life, where Ein Sof (God) reveals Herself. The left side represents the feminine םי (Mi) side of man – the Pillar of Severity. It contains three sefirot: Binah (Understanding), Gevurah (Power or Judgement) and Hod (Splendor). The right side represents the masculine מָה (Mah) side of man – the Pillar of Mercy. It also contains three sefirot: Hokhmah (Wisdom), Hesed (Love) and Netsah (Endurance). The centre represents equilibrium, balance and virtue. It has four sefirot rather than three: Keter (Crown), Tif’eret (Beauty), Yesod (Foundation) and Malkhut (Kingdom, also known as Shekhinah or Presence).[12] So when we talk of letters and drawn from above to below, we are speaking not only of the creation of earth, but the creation of the Tree of Life and all of the stars in the sky.

Gender Complexities in The Merchant of Venice

The imageries in Shakespeare and Emilia Bassano’s Salve are so cunning that scholars have not realized the origins for centuries.

Portia & Bassanio

|

Figure 1 – Tree of Life, Excerpt from ‘Genesis of the Shakespearean Works’ with Pillars added. © Copyright 2017, Bassano Publishing House. |

We have Portia (Katherine Bassano, nee Fieschi) who is a rich, beautiful, fearless noblewoman, full of splendour and sincerity, depicted as the sefira of Hod, in the feminine םי (Mi) side of the Tree of Life. With the caskets, her father set up a scenario for her suitor whereby her husband must begin the earthly pilgrimage to the Temple (grand palace in the play) and the divine procession of emanation to Shekhinah, and in doing so Bassanio moves from the male side of love (Hesed), to wisdom (Hokhmah) as he walks towards the grand palace (Temple) by faith, he is overwhelmed by understanding (Binah), as the letter ה (he) departs and the י (yod) enters, uniting with balance in the sefirots and Shekhinah (Malkhut) walks with him into the room. He does not need to ponder the caskets, but immediately chooses lead, drawing from the manifest presence of Shekhinah who stands with them as they embrace.

Portia

After Bassanio left, Portia came up with an idea to go to Venice disguised as men. Portia turns to her servant Balthasar and asks her to go to her cousin in Padua, Dr Bellario (also a real Dr Hieronymus Benalius, who lived in Anotnio Bassano’s mansion in Mark Lane, London), with a letter and bring the notes and garments he would give. Here again, Portia is transformed from a rich, beautiful, fearless noblewoman, full of splendour and sincerity, depicted as the sefira of Hod, in the feminine םי (Mi) side of the Tree of Life, as the ‘letter’ is read (letter ה (he) departs and the י (yod) enters), to the masculine side of the Tree of Life, to the sefira of Hokhmah, with a selfless act risking her own life to parade as Balthasar. With Hokhmah, she is afforded the wisdom of Solomon, and her soul has the power of intuitive insight, flashing lightning-like light across her consciousness of ‘what is’ מָה (Mah – also masculine), with the ability to look deeply at some aspect of reality and extracts the conceptual success of the future םי (Mi) (Binah – feminine), almost like a foresight of what can and will take place according to the Will of God (Keter – balance – power – omnipotence).

In this case, Portia had transformed from the sefira of Hod in feminine םי (Mi) side of the Tree of Life to the masculine מָה (Mah) side as the letter was read. She had the wisdom of Hokhmah and entered a theological yet legal debate regarding the law and justice, enthusing Shylock to prepare the knife to cut a pound of flesh from Antonio’s bosom, giving Shylock an opportunity to repent and settle the matter, but he refused up to ten times the amount due by Bassanio.

Shylock

Here is where Shylock as a Jew, one of God’s chosen, protector of the covenant and the Torah, was in the pillar of equilibrium, balance and virtue, from the sefira of Yesod (Foundation and Covenant). However, whilst all the beautiful images are in the sefira of Yesod, it also allows one to access the images of lust, greed, hatred, revenge, anger and violence against others. This is where Shylock allowed himself to dwell too long, and instead of accepting a reasonable settlement even up to ten times what he was due, he reacted out of his ‘ego’ and therein allowed the demon Satan to influence his life.[13]

Instead, he should have realized it was his ‘ego’ and not reacted, then bitterness couldn’t have set a foothold, then any decision after that was set upon revenge – his entire world was blinded by his desire for revenge and in this case, the death of innocent Antonio who went surety for Bassanio. As I noted in my book ‘Genesis of the Shakespearean Works’, this is realizing your ego ‘reaction’ is the enemy, thus we should shut down our reactive system to allow the light of God in and be proactive via the 99% realm.[14] The 99% is a supernal realm of perfection beyond human perception – the source of all blessings, wisdom, pleasure, good fortune, and miracles – where all the answers to our prayers reside (Tif’eret). However, it is up to us to overpower our inclinations, and Shylock rejected to walk with Shekhinah, therefore he went to the sefira of Gevurah in the feminine םי (Mi) side of the Tree of Life. This is a place of justice and judgement, where Elohim takes revenge against the wicked who rebel against YHVH.

Elohim is known as the essence of the consuming fire in the sefira of Gevurah that can bring judgement, make ill, and even death on the one hand, and bring life, sustain, heal, and blessing on the other. Shylock out of an ego ‘reaction’ was transformed from the sefira of Yesod from the central part of the Tree of Life reflecting balance and virtue, to the feminine םי (Mi) side as Portia read the letter, Shylock invoked Satan and ultimately chose judgement when he languished in the thought of the murder of Antonio, a competitor Christian merchant in Venice, where he delighted, “Most learned Iudge, a sentence, come prepare” as he prepared the knife to cut a pound of flesh from Antonio’s bosom in open court for all to see. Elohim judged him harshly, whereby Portia states that half of Shylock’s property would go to the state and the other half to Antonio. Portia orders Shylock to beg for mercy, whereby the tables are turned by Elohim, and the Doge declares he will grant mercy by sparing Shylock’s life and imposes a fine, rather than half of Shylock’s estate. Shylock asserts they may as well take his life without his estate and his livelihood.

Antonio offers to return his share of Shylock’s estate on the basis that Shylock becomes a Christian and record a gift of all his possessions unto his son Lorenzo and his daughter Jessica.[15] Shylock asks for leave because he states “I am not well” but consents.[16] As I stated above, Shylock had chosen the sefira of Gevurah, and had chosen judgement by Elohim because of his ‘reaction’ of ego. Elohim judged him harshly, made him unwell, almost took his life, but then granted mercy and brought him to the place of repentance, where he surrendered his own life before Elohim in the statement, “take my life and all”.[17]

Gender Discussion and Historical Background of the Character of Antonio

We have discussed the Kabbalistic gender complexity of the characters Bassanio, Portia, and Shylock. Now we need to understand the very interesting, yet different, aspect of the character Antonio. Many modern scholars and film directors have erroneously suggested that Antonio and Bassanio might have been gay, such as the 2004 film The Merchant of Venice directed by Michael Radford, where the ABC News reported that even his actors who played the roles did not agree with the director’s ideals about what the kiss meant (which is not in the First Folio).[18] This has been deduced from the line in Act 1, Scene 1 where Solarino is speaking with Antonio and Salanio, and says, “Heere comes Bassanio, Your most noble Kinsman.”[19] Honestly, I don’t know how they could deduce anyone is gay from that single line. It could refer to Antonio or Salanio, or simply, ‘Hey Antonio, here comes your brother Bassanio’. If these scholars and film directors knew the historical background and had some Kabbalistic understanding of the mind of the dramatists and what they were trying to teach, I think they would laugh at their own conclusions.

As I explained earlier in this paper, The Merchant of Venice was penned and performed prior to 1576 when Shakespeare was but a boy living with his parents in Stratford-upon-Avon. The story is a true story about Antonio Bassano, The Merchant of Venice, and his undying love for his brother Bassanio (Baptista Bassano) and his real life rich, beautiful, fearless noblewoman bride Portia (Katherine Bassano, nee Fieschi) who fights for Antonio’s life in the Venetian Court. Antonio Bassano married Elena de Nasi (a Jewish Nasi princess) in Venice on 10 August 1536 and his brother Jacomo Bassano married her sister Julia de Nasi (a Jewish Nasi princess), probably on the same day. Both were daughters of the Venetian banker, moneylender, and silk merchant named Benedetto de Nasi (the Great), who was of the Nasi-Benveniste lineages of Don Vidal Benveniste, a prominent Spanish Judaist scholar of Saragossa, titled ‘de la Cavalleria’ by the Templar Knights.[20] They are of the same lineage as the Nasi family that can be traced all the way back to Rabbi Solomon Bar Isaac (Shlomo Yitzhaki) known as Rashi (1040-1105), an astounding discovery by Rabbi Billy Phillips of the Kabbalah Centre in the USA.[21] Interestingly, some of Rashi’s works are cited in the Shakespearean works. Benedetto de Nasi might well have been the character of Shylock, because in real life, he was a Jewish moneylender. To date, I have not found a legal case between the pair, but that is not to say it didn’t occur or will be found at a later date; I could only spend a short time in the records office in Venice searching for documents.

There was a real life court case circa 1571 in the Venetian court between Jacomo’s daughter, Orsetto Bassano, against the five English brothers after the death of Jacomo Bassano regarding the property that encompassed the family’s musical instrument manufacturing business in the Veneto region; consequently there is clear evidence of a falling out within the family. The action in the Venetian court was taken against Antonio, Jasper and John who ended up settling out of court. This court case and the entire ordeal is encapsulated in the play of The Tempest.[22]

In summary, in real life we know that Antonio Bassano married Elena de Nasi, and considering he showed a ‘brotherly’ love for Bassanio (Baptista Bassano), we can deduce Antonio was in fact heterosexual. However, again the gender complexity behind the character of Antonio is entirely Kabbalistic in nature; like that of Portia, Bassanio and Shylock.

Antonio was locked up in a jail cell in Venice awaiting his trial, with Shylock demanding his pound of flesh, citing his bond as his right for vengeance. At the beginning of Act 4, we find the following stage directions, where Antonio, Bassanio and Gratiano are identified as the “Magnificoes”:

Enter the Duke, the Magnificoes, Anthonio, Bassanio, and

Gratiano.

Interestingly, the word “Magnificoes” identifying Antonio and his brother Baptista, means a nobleman of Venice.[23] The Doge, or Duke in this case, relayed his apology for such a great dishonour upon Antonio, for in fact the Doge of Venice up until December 1538 was Andrea Gritti da Sebenico, a family friend and grandfather of Santo Gritti da Sebenico who ended up marrying Orsetta Bassano, Jacomo Bassano’s real life daughter.[24] The Duke’s apology:

I am sorry for thee, thou art come to answere

A stonie aduersary, an inhumane wretch,

Vncapable of pitty, voyd, and empty

From any dram of mercie.[25]

Kabbalistic Gender Complexities of Antonio

Antonio replied to the Doge with one of the most beautiful Kabbalistic expressions of virtue within the Shakespearean cannon:

I haue heard

Your Grace hath tane great paines to qualifie

His rigorous course: but since he stands obdurate,

And that no lawful meanes can carrie me

Out of his enuies reach, I do oppose

My patience to his fury, and am arm’d

To suffer with a quietnesse of spirit,

The very tiranny and rage of his.[26]

Whilst Portia had transformed from the feminine side of the Tree of Life to the masculine side as the letter was read, she had the wisdom of Hokhmah; Shylock as a Jew, one of God’s chosen, protector of the covenant and the Torah, allowed the images of lust, greed, hatred, revenge, and ultimately violence against Antonio to dwell too long, and reacted out of his ‘ego’ and therein allowed the demon Satan to influence his life; whereas Antonio in his jail cell contemplating his fate, “out of his enemies reach, I do oppose” – my patience to his fury, and am armed to suffer with a quietness of spirit, the very tyranny and rage of his – Antonio allowed a miracle to take place in his own heart and rose to Shekhinah!

Antonio out of love for his brother Bassanio, gave an undertaking of surety. This in Kabbalistic terms is the covenant love of the sefira of Hesed in the masculine מָה (Mah) side of man – the Pillar of Mercy. It was a selfless act, drawing from the wisdom and selflessness of Hokhmah. As he prepared himself in the jail cell to face his ultimate demise, unlike Shylock who sought revenge, Antonio realized it was ‘ego’ and did not react as Shylock did. He realized his ego ‘reaction’ is the enemy, and shut down his reactive system to allow the light of God in and was proactive via the 99% realm.[27] Antonio was sincere in his resolve to Bassanio, and was transformed from the male side of the Tree of Life to the female side, to the sefira of Hod. With a sincere heart, ready to meet his maker and face judgement, the ‘letter’ is read (letter ה (he) departs and the י (yod) enters) and he is transformed to the 99% supernal (heavenly) realm of perfection beyond human perception – the source of all blessings, wisdom, pleasure, good fortune, and miracles – where all the answers to our prayers reside, the sefira of Tif’eret. It is from Tif’eret where Antonio walks his earthly pilgrimage to the Temple, and is met by the divine procession of emanation to Shekhinah, or put it another way, he is met by the divine manifestation of Shekhinah.

As I discussed earlier, the verse in the Zohar teaches that the physical and spiritual are linked, whereby as the procession to the Temple (or courtroom), Elohim walked within the crowd, and conducted (as a music conductor) them to the house of Elohim with jubilant shouts of praise from the festive congregation.[28] Thus, Antonio received great blessing from Ein Sof (God) and his accuser was punished accordingly.

Thus, the gender complexities of The Merchant of Venice have absolutely nothing to do with sexuality or sexual persuasion, but it has everything to do with recognizing one’s ego as the ‘reaction’ that would allow the demon Satan to influence one’s life. Only by recognizing it is our ego and shutting down our reactive system can we be transformed to the 99% supernal realm of perfection beyond human perception and repair the world. This is the Jewish doctrine of Tikkun Olam found in the Mishnah and the Bassano’s Kabbalistic teachings that are weaved throughout their literary works and all of the Shakespearean plays.

______________________________________

For further information on the Bassano family and their connection to the Shakespearean works, please read my major academic work of ‘Genesis of the Shakespearean Works’. More information is also available on my website at www.petermatthews.com.au, or you can like my Facebook page to keep abreast of any updated material I find. My academia profile is also available here.

[1] Encyclopedia: Querelle Des Femmes, (2004) The Gale Group Inc. https://www.encyclopedia.com/humanities/encyclopedias-almanacs-transcripts-and-maps/querelle-des-femmes

[2] Knox, John (1558), The First Blast of the Trumpet Against the Monstruous Regiment of Women, Reprint 1571 Edinburgh.

[3] Gosson, Stephen (1579) The School of Abuse, reprinted in 1841 for the Shakespeare Society including an introduction about the author. For the original unedited copy: http://www.archive.org/stream/schoolabusecont00collgoog#page/n7/mode/1up

[4] F1, MV 4.1.2010-3.

[5] JewishEncylcopedia.com: Piyyut, The unedited full text of the 1906 Jewish Encyclopaedia, www.jewishencyclopaedia.com

[6] Matt, Daniel (2002-2014), The Zohar, Pritzker Edition, Stanford University Press, Sections 1:2(a) in Vol 1, p9.

[7] Ibid.

[8] Ibid.

[9] Tuchman, Lauren (2012), The Shekhinah or The Divine Presence or Divine Feminine in Judaism, https://www.stateofformation.org/2012/01/the-shekhinah-or-the-divine-presence-or-divine-feminine-in-judaism/

[10] Mishnah, Tractate Megillah, 29A https://www.sefaria.org/Daf_Shevui_to_Megillah.29a?lang=bi

[11] Matt, Daniel (2002-2014), The Zohar, Pritzker Edition, Stanford University Press, Sections 1:2(a) in Vol 1, p9.

[12] Matt, Daniel (2002-2014), The Zohar, Pritzker Edition, Stanford University Press, Volume 1, Entry page: The Ten Sefirot.

[13] Teaching by Rabbi Billy Phillips from the Rav Berg. Go to the Kabbalah Centre for in depth study, or visit his YouTube site: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=IG_tRFg4xQg&t=1s

[14] Berg, Yehuda (2003), The Power of Kabbalah, Hodder and Stoughton, p93.

[15] F1, MV 4.1.2298-2308.

[16] F1, MV 4.1.2314-6.

[17] F1, MV 4.1.2292.

[18] ABC News 29 Dec 2004, Was the Merchant of Venice gay? http://www.abc.net.au/news/2004-12-29/was-the-merchant-of-venice-gay/609696

[19] F1, MV 1.1.63-4.

[20] Matthews, Dr Peter D (2013), Shakespeare Exhumed: The Bassano Chronicles, Bassano Publishing House, Australia, ISBN 9780987365255, pp. 61-2.

[21] Personal discussions with Billy who provided me with a genealogy to prove it from my own research that linked the connections for him. The discovery is wholly and solely by Billy Phillips. He just used some of my research, and I helped with further research on meetings with and prophecies of Rashi.

[22] Matthews, Dr Peter D (2013), Shakespeare Exhumed: The Bassano Chronicles, Bassano Publishing House, Australia, ISBN 9780987365255, pp. 212-3.

[23] Merriam Webster Dictionary: magnifico, 2018, Merriam-Webster. https://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/magnifico

[24] Matthews, Dr Peter D (2013), Shakespeare Exhumed: The Bassano Chronicles, Bassano Publishing House, Stanthorpe, Queensland, Australia, ISBN 9780987365255, p127.

[25] F1, MV 4.1.1905-9.

[26] F1, MV 4.1.1910-7.

[27] Berg, Yehuda (2003), The Power of Kabbalah, Hodder and Stoughton, p93.

[28] Matt, Daniel (2002-2014), The Zohar, Pritzker Edition, Stanford University Press, Sections 1:2(a) in Vol 1, p9.