The Bassanos

Jewish Guardians of the Ancient Arts

Dr Peter D Matthews

For centuries scholars have grappled with the fact that many of the Shakespearean characters are members of the Bassano family, but few have considered them as serious candidates for the dramatists of the Shakespearean works, until I released Shakespeare Exhumed: The Bassano Chronicles in 2013. In the lead up to the release of Genesis of the Shakespeare Works in early 2017, I thought it was time to release a paper containing some of my research into the Bassano family gathered over the last 14 years while forensically examining many thousands of relevant documents throughout the world.

Origin of the Surname

The name Bassano in Italian is developed from their earliest name ‘de Bassan’ from the Latin word ‘Bassan’ or ‘Bassanus’ that originates from a Hebrew root word באסאן transliterated as ‘Basan’ . In the old Jewish Cemetery of Venice (San Nicolò on the Lido) there are 19 descendants of Jacomo Bassano buried in the cemetery, 14 of which I managed to locate. Some tombstones are inscribed in Italian and some are in Hebrew, spelt in various ways: de Bassan, Bassano, Bassani, באסאן (Bassano), באסאני (Bassani), but interestingly, also a few variants: הַבָּשָׁן (Bassan), בסני (Bassani), and בסנו (Bassano), all probably from the same family.

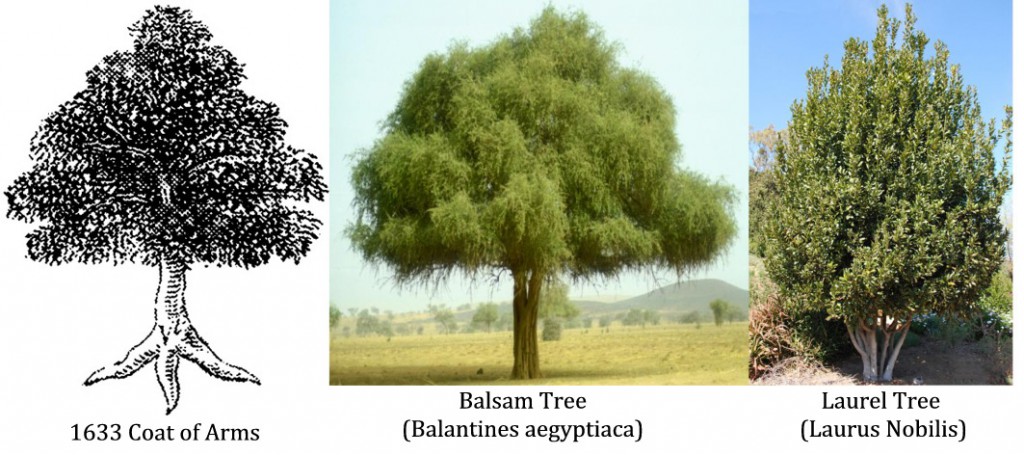

The Hebrew word באסאן (Bassano) or בסנו (Bassano) literally means “tree”, speaking specifically of the “Tree of Life” – a model of virtue, which was taken from the Greek text of Philo and the Hebrew Midrash, which is the very source of the Sonnets, and many of the Shakespearean plays. It is not just any “tree” (Hebrew עֵץ), but specifically the “Tree of Life”. The Tree of Life was also adopted by the Bassano family as their main emblem on their earliest 16th century coat of arms.

Their original surname in Spain was “de Bazán” (בזאן), another variant on the Bassano name. The ‘de’ in front is a Spanish word, meaning ‘from’, thus the family were ‘from Bassan’ taking into consideration the Latin, Greek and Hebrew roots. The Hebrew root word for Bassano means: ‘smooth and fertile land beneath the range’ in Deuteronomy, but also refers to ‘prominent men’ in Zechariah 11:2, and in a feminine sense of ‘luxurious women’ in Amos 4:1.[1] Bassano Del Grappa in Northern Italy is smooth and fertile lands beneath the range of Monte Grappa. There is a valid reason why they chose to live in Bassan, Venezia (later renamed Bassano, then renamed Bassano Del Grappa in 1928 after World War I).

Then there is the Greek word “βάσανος” that some erroneously claim is the origin, which transliterates as “basanos”. It means “torture and torment”, specifically examination by torture, referring to testing gold and silver with a dark stone, namely a Lydian stone.[2] It is effectively a touchstone. One could assume from this that the Bassanos could have named themselves Bassano because they were Lydians, but you would be wrong in this conclusion. The Lydians were ancient Anatolians, who were of ancient Hitite origin, not Hebrew origin.

While the Hitities were friends with Abraham in the Bible, Antonio Bassano in his 1544 Sefer ha-Refu’ot (Book of Remedies) refers to his ‘true Hebrew’ heritage from the land of his forefathers. He also tells us that he was a son of David, from the lineage of Shem. The land of הַבָּשָׁן (Bassan Latin) in Israel was given to the descendants of Shem. Much of the Bassano’s emblems and literary works of Hebraic antiquity, particularly of the Essenes, originate from this very region in Israel. Therefore, I believe their ancestors originated from הַבָּשָׁן – or ‘from Bassan’ in Israel, prior to Spain and Venezia.

The Bassano family were cited in Venetian records as “Ser Alvise da Bassan, di maestro Jeronimo” in 1515.[3] The ‘Ser’ is short for ‘Signore’ meaning ‘Sir’. Thus, the surname is recorded as ‘da bassan’. The ‘da’ before a name in Italian also means ‘from’ Bassan, just like the Spanish ‘de Bazán’.

The brothers are first recorded in England in 1517 but not by name, only reputation. It was not until 21-6 June 1528 that the brothers are recorded as ‘de Jeronyny’ in a payment record at Dorset:

Lewes de Jeronyny and others the King’s sagabottes.[4]

By 1531, they are found in England again as ‘de Jeronimo’ or put it another way, ‘the sons of Jeronimo’:

To Mark Antony, Loyes de Jeronom, Pylgrym Maiohn, Jasper de Jeronimo, John de Jeronimo, 7l. 17s. 6d

This refers to them being the sons of Hieronymus de Bassanus (Latin), or Jeronimo Bassano in English. This is not uncommon, particularly for English records, as young men and women were often named with reference to their father. Emilia Bassano was actually recorded at her Christening as ‘Emillia Baptist’ after her father Baptista Bassano, similar to how the Bassano brothers were named after Jeronimo.[5] This is not surprising because Jeronimo Bassano was a famous Master Kabbalist, physician, teacher, author (later banned by the Catholic Church as a heretic in the 1559 Index Librorum Prohibitorum), musician, and maker of diverse musical instruments in Venezia.

The Bassano brothers emigrated from Venice on 1 October 1539,[6] and were permanently employed in the English Court in April 1540. Their surname is recorded as ‘de basam’ in Henry VIII’s Letters and Papers 21-30 April 1540 granting them stipends (a salary):

Alinxus, John, Anthony, Jasper, and Baptista de Basam, brothers in the science or art of music. Grant of the following stipends, viz.:—

to Alinxus, 50l. a year; to John, 2s. 4d. a day; and to each of the others, 20d. a day. Hamptoncourt, 6 Apr. 31 Hen. VIII. Del. Westm., 14 Apr.—P.S. Pat. p. 5, m. 38. Rym., XIV. 657.[7]

By 1544, Antonio Bassano refers to himself as ‘Antonio de Bassan’ in his Sefer ha-Refu’ot (Book of Remedies).[8] A year later, they are mentioned in a record as residing in the London Charterhouse, when Henry VIII granted the property to Sir Edward North, subject to permitting the ‘Bassani’ (another version of ‘de Bassan’) brothers rent free while they remain in the King’s Service:

The said Sir Edward to permit Louis Gaspar. John, John Baptist and Anthony Bassani. Italians, the King’s servants, to enjoy their houses, &c, as long as they remain in the King’s service.[9]

On 10 December 1565, Antonio de Bassan is recorded as ‘Mr. Anthony Bassanye, one of the Queene’s Musisyans’ in the baptism entry of Thomas Dutpotzo.[10] Then his son, Mark Anthony Bassano, is cited as ‘Bassano’ when soldiers tried to arrest him in 1585, thinking he was a Spaniard.[11]

Thus the ‘de Bassan’ name has been chronicled as de Bassan, de Basam, Bassani, Bassanye, and Bassano throughout the first and second generation family members who emigrated to London.

To be ‘il Piva’, or not to be? That is the question.

In recent years, I have spent a considerable amount of time researching documents in the archives of Venice, Bassano Del Grappa, and Crespano Del Grappa. While I was in Venezia, I researched Alessio Ruffatti’s 1998 theory that the Bassano’s were previously named ‘il Piva’. The first document Ruffatti found was a record of 1577 in a physician’s diary by the name of Lorenzo Marucini regarding a Maestro Hieronymus, which I have translated to English as follows:

Maestro Hieronymus, called il Piva (the bagpipe), the inventor of a new low wind instrument, the most excellent Pifaro, and in the employ of the illustrious Signor (Doge) of Venice, which Hebbe bore three musician sons by him, who along with his father were later scholars for the Serene Queen of England with great skill in his handmade flutes, of whom made his mark (‘!!’ and ‘HIE(RO).S.’ for Hieronymus), they are held in great veneration hereafter as Musicians, and they are well paid where they are. (brackets mine)[12]

Clearly, this does record Hieronymus de Bassanus (Jeronimo Bassano) as being ‘called il Piva’ by his local doctor. Marucini also states that only three sons were born by his wife ‘Hebbe’, with the inference that he knew her. Therefore, this entry would suggest that the eldest three brothers were born to another wife. This entry is quite fascinating because Hebbe (Hebe) is the name of the ancient Greek goddess of youth, who was the cupbearer to the gods of Mount Olympus. Hebe served divine ambrosia at the heavenly feast, just like the Bassano’s Kabbalistic imagery on their coat-of-arms with bees pouring out divine ambrosia through the tree of life, enveloped in unity.

In the end, Hebe married Heracles (Hercules) after his apotheosis. I viewed a copy of the Placitum of 998 AD in the Biblioteca Nazionale Marciana, which commences the official history of Bassan (Latin, later renamed Bassano), although Bassano has a far more graphic ancient connection to the Grecian hero Hercules dating back between 4th to 1st century BC.[13] Yet scholars have wondered why Hercules is cited 36 times in the Shakespearean works, once even compared to Adam Kadmon (Jewish Kabbalah) in Much Ado About Nothing. Had scholars visited Bassano Del Grappa and Venice, they would have understood many of the Shakespearean characters, such as Prospero, Othello, Bassanio, and so forth, all of which are found on the walls of the painted city, in the museum, and amongst the ancient records of the city.

In Homer’s Illiad, Queenly Hebe is recorded as follows:

Now the gods, seated by the side of Zeus, were holding assembly on the golden floor, and in their midst the queenly Hebe poured them nectar, and they with golden goblets pledged one the other as they looked forth upon the city of the Trojans.[14]

Imageries of this nectar are found in Troilus and Cressida, Two Gentlemen of Verona, and in the poem of Venus and Adonis. In Act 4, Scene 3 of As You Like It, Silvius’ declaration of love for Phebe (Hebe, Hebbe) speaks of ‘my erand’ – the gift of ‘fair youth’:

My errand is to you, faire youth,

My gentle Phebe, did bid me giue you this:

I know not the contents, but as I guesse

By the sterne brow, and waspish action

Which she did vse, as she was writing of it,

It beares an angry tenure; pardon me,

I am but as a guiltlesse messenger.[15]

It also cites a ‘waspish action’ of a bee. This canto can be viewed as an imagery of the Bassano family and their mother Hebbe pouring divine ambrosia into their own hearts.

The second interesting record found was a deed or lease in 1481 of a vacant woodland field of legumes in the town of Crespano del Grappa from the Monastery of Santa Croce in Bassano del Grappa:

Venerabilis in Christo Pater Dominus Domnus Andrea de Carpi ordinis Sancti Benedicti […] prior monasterii Sancte crucus […] investivit ser Baptistam Piva quondam Andree de Crespano ibidem presentem et nee nomine et vice Domne Bonae eius uxoris et Zanantonii et Hieronimi filiorum suorum […] de una terrae boschivae quae potest esse circa quator campos positos in pertinentiis villae Crespani in contrada de legumis.[16]

An English translation is as follows:

The Venerable Father in Christ, the Holy One, Blessed be the LORD liveth Andrea de Carpi and born […] prior of the monastery of Santa Croce […] the present, invested in the same place, and did not Sgn. Baptista Piva (Baptista, the bagpipe player) and Andree de Crespano (Andrea from Crespano) of the same name and place, and the late Master Andrea and his sons Jeronimo, and Zanantonio, his brother […] one of the four fields, which can affect any of the woodlands in the country of the legumes, laid in the appurtenances (property right) of the towns of Crespano.

The Church in question that leased the vacant woodland was La Chiesa di Santa Croce (The Church of the Holy Cross) where the famous Bassano poet, Teofilo Folengo, is entombed, who passed away around the same time as Jeronimo Bassano. Folengo wrote under the pseudonym of Merlin Cocai, in the same macaronic style as much of the Shakespearean works. I suggest this was done intentionally so that the true authors of the Shakespearean works would be discovered by historians centuries later, linking them with other poets from Bassano Del Grappa.

Many have asked why would the Bassanos lease a vacant plot of woodland with legumes? The Bassano family did in fact lease numerous lots of grazing land in England for grazing cattle. This is because calf skins were used in their musical instrument manufacturing business as well as export in their merchant business. Could the Bassanos have leased vacant land for grazing cattle in Crespano Del Grappa even as early as 1481? As a retired cattleman myself, and having examined the soil and topography in Crespano, this is quite plausible during the summer months, but probably not in winter.

As to the name, the above Latin document cited by Ruffatti doesn’t actually assert their name was ‘il Piva’, but uses “nomine et vice” meaning “of the same name and place”. This record speaks of Baptista (the bagpipe player) and Andrea (of Crespano) being of the same name and place, and the late Master or Maestro Andrea and his sons Jeronimo and Zanantonio, who may well have been in Bassano del Grappa, considering the Church in question was in Bassano. However, a local physician from Bassano del Grappa recorded Jeronimo’s name with the words ‘called il Piva’. Could this have merely been a nickname given by the Church or the Doge of Venice?

‘Il Piva’ is a combination of Latin and Italian, and is loosely translated as ‘the bagpipe’ by English speaking people, but not necessarily by Italians today. The word ‘piva’ is not a bagpipe in the Italian language, because a bagpipe is referred to as ‘la cornamusa’. Could ‘piva’ be referring to a shawm? No, the Italian word for a shawm is ‘la ciaramella’. The word ‘piva’ is Latin for ‘the music from an early Venetian bagpipe’. I learned in Venice that the medieval usage of ‘il piva’ was used for a ‘player’ of ‘the bagpipe’ with the connotation ‘of being humiliated for not being a good musician’. The Bassano family, namely Hieronymus de Bassanus onwards, were skilled musicians of the highest calibre. We must then ask: why did their local physician refer to Jeronimo as not being a good musician, while accolading him as being held in great veneration?

A clue can be found in the Bassano brother’s departure from Venice. In a letter from Edmund Harvel to Cromwell dated 4 October 1539, the Bassanos were so keen to leave Venice on 1 October 1540:

The musicians were so desirous of seeing the King that, in spite of the refusal to give them licence, they started for England on the 1st. They are four brothers esteemed above all others in the city.[17]

But why were they so keen to leave, especially when we know they were well paid in the employment of the Doge? The Bassanos had travelled back and forth to England for some years, so they were well known to Henry VIII, but the answer lies in the Doge’s refusal to give them licence to leave Venice. In a letter by Alvise Bassano in 1552, he wrote how they were “in jeopardy of utter banishment from Venice” because of departing without licence.[18] Prior to their departure, the Doge of Venice was Andrea Gritti de Sebenico, a close friend of the family and fellow Kabbalist. Andrea’s grandson, Santo Gritti da Sebenico, married Orsetta Bassano, daughter of Jacomo Bassano and Julia de Nasi. Around Christmas of December 1538, Andrea Gritti died and Pietro Lando was elected Doge in 1539.[19] It is clear the Bassanos were at enmity with Lando, hence the reason the Bassanos departed Venice in haste without licence.

In 1502, when the Bassanos moved to Venice, the Doge was Leonardo Loredan, who served as Doge from 1501 to 1521. You will note Leonardo in The Merchant of Venice is Bassanio’s servant, thereby reversing their roles. Having researched many of the Doges of Venice, particularly those with ties to Bassano del Grappa, there is one family that stands out – the Vendramin family of merchants, bankers, and theatre owners. It was Andrea Vendramin who served as Doge between 1476 and 1478 just prior to the 1481 lease. An interesting fact in the Venetian records is where a group of young nobles were running through the streets at night singing Jewish hymns in 1593. One of the men arrested and put to death was a member of the Vendramin family.[20] Whether he was a Jew or associated with Jews is unknown, but we do know that a later descendant, Andrea Vendramin of Venice, in 1650 did print Jewish Kabbalistic books, such as the ‘Zohorei Hammah’, a condensed commentary on the Bassano’s earlier 1558-60 Zohar.[21] Might have Doge Vendramin been the Bassano’s earliest connection to the Venetian court, after all, their families moved in the very same circles?

The Doge after Vendramin was Giovanni Ser di Mocenigo, Jr, another military commander like Pietro Lando. Could Doge Mocenigo have dubbed the de Bassan family ‘il Piva’? Based upon the fact that there are numerous documents relating to the ‘de Bassan’ and ‘Bassano’ family in Bassano Del Grappa and Venice, including early records of them in the Spanish part of the Jewish Ghetto in Venice, we must conclude that their names were ‘de Bassan’, but at some stage early in the piece, they were dubbed ‘il Piva’ or ‘players of the bagpipe’ with the connotation ‘of being humiliated for not being a good musician’. Alternatively, perhaps, these early “Songbirds” called themselves ‘il Piva’ almost in a satirical manner.

We must not forget genetics. For example, I am the spitting image of an early portrait of my 6th great grandfather. If I dressed in his relegia, you would swear the portrait is of me. It is quite uncanny. The fact is, DNA doesn’t lie! While I have not taken DNA of the Piva family and compared it to the Bassano family as yet, I must acknowledge many of the modern Bassano family do in fact resemble early portraits and photography of their ancestors. While visiting Bassano Del Grappa and Crespano Del Grappa, I visited every cemetery (yes quite morbid!) and found a number of Piva graves with photographs dating back to the late 19th century. There was no a single member of the family that resemble any living or recently deceased Bassano family descendants of England, USA, or Australia. In fact, a number of the Piva family in Crespano appear to have a deformed oddly shaped head. Therefore, they simply cannot be related to the Bassano family that emigrated to England.

In Antonio Bassano’s 1544 Sefer ha-Refu’ot (Book of Remedies), he recorded his surname as ‘de Bassan’. The ‘de Bassan’ or ‘Bassano’ family can traced back to a long lineage of Jewish Rabbis and Master Kabbalists across Italy and Spain. Venetian and Papal records cite Hieronymus de Bassanus, Latin for Jeronimo Bassano, as being a maestro, maker of diverse musical instruments, master kabbalist, physician, teacher, and author. Jeronimo was eventually dubbed a ‘heretic’ in 1559 by the Catholic Church, some fifteen years after his death, and his volumes of Hebrew books on kabbalah, medicine, and comedy [plays] were banned and burnt under the Index Librorum Prohibitorum of 1559.

On the basis that Jeronimo Bassano is cited as ‘de Bassan’ and ‘de Bassanus’ in various documents throughout Italy and England, and the fact that Antonio referred to himself as a ‘de Bassan’, coupled with the fact that they were “called il Piva” in Bassano Del Grappa, but not necessarily named il Piva, we must conclude that ‘il Piva’ was simply an occupation, possibly dubbed by the Doge – not their natural born Hebrew surname. Their surname is ‘Bassano’ or ‘Bassani’ in Italian, from the Hebrew word בסנו literally meaning “tree”, speaking specifically of the “Tree of Life”.

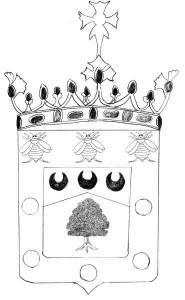

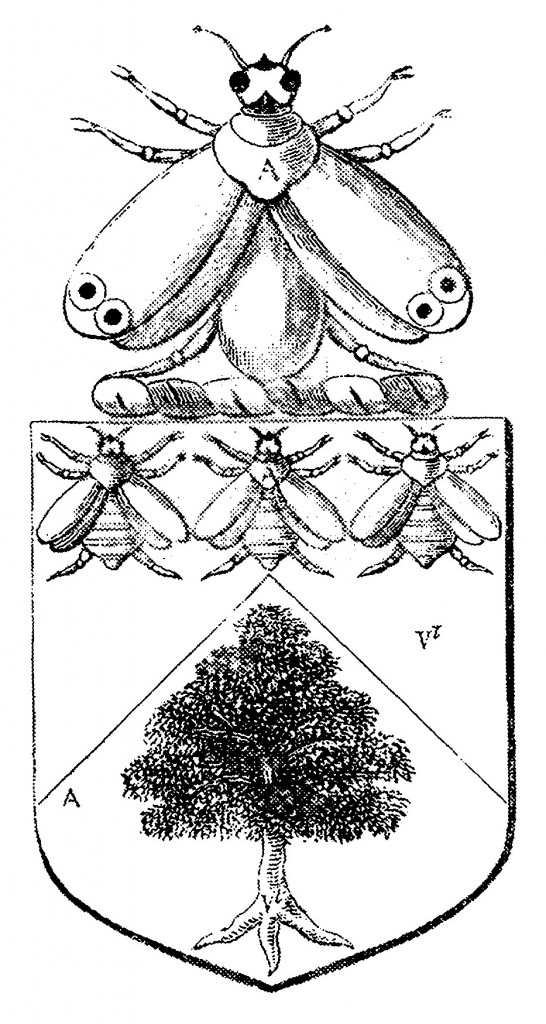

Coat of Arms

The earliest Bassano family coat-of-arms of 1540 reproduced below, contains three drone-like honey bees over the Tree of Life, which in Kabbalistic terms is a model of virtue akin to the divine ambrosia being poured out through the tree of life, enveloped in unity. The inscription under the coat-of-arms is ‘gratia nos dirige’ meaning ‘the favour of God directs us’ adapted from Psalm 37:23 and Proverbs 3:6. The three drone-like honey bees above the Tree of Life represents the ten sefirots in unity, commonly call Da’at (דעת in the Hebrew), referring to a ‘higher knowledge’ of wisdom, literature, understanding or discernment,[22] almost like a deeper reality in the renewal of our minds with a ‘divine spark’ of creation, a creative force in unity with God.[23] Essene Kabbalists use this word in regards to ‘prophetic knowledge’.

The earliest Bassano coat-of-arms on a building in the Spanish part of the Jewish Ghetto in Venice beholds a Tree of Life (below). Near it, inside a building, is a tribute to members of the Bassano family.

|

Figure 3 – Coat-of-Arms with Tree of Life in the Jewish Ghetto of Venice. |

A similar coat-of-arms with the Tree of Life is found on a canal fronted building with merchant access to the roof space in San Maurizio, Venice. This is very interesting as it has three Tree of Life coat-of-arms affixed to the front of the building that were significantly eroded and two cameos. Historical property records confirm an owner in the last century had one of coat-of-arms replicated by taking a mould and reaffixing it over one of the existing. It is the small ochre-toned building to the left of Palazzo Corner della Ca’ Grande with a garden to the right of the home in the below photograph. Interestingly, it also has four Romeo & Juliet style balconies and is two doors away from the original Gritti Palace.

|

Figure 4 – Canal view of Bassano Casa, San Maurizio (left) |

The City of Venice records office confirm the building is as an “ancient Venetian home”,[24] although no surname is recorded. Records simply confirm it was previously owned by a family of merchants and musicians in the early 16th century who served Doge Andrea Gritti. Now this does sound quite interesting, considering the Bassanos were recorded in that very street in in the parish of San Maurizio, and they did in fact serve Doge Andrea Gritti as musicians from 1523 until he passed away in December 1538. In fact, Jacomo Bassano’s daughter married the grandson of Doge Andrea Gritti, so the Bassano’s were very close indeed to the Doge’s family. It was soon after the death of Doge Andrea Gritti that the Bassanos departed for England on 1 October 1539.

|

Figure 5 – Canal view of Bassano Casa, San Maurizio |

Having examined the property records of the State Archives of Venice, there are very few scant records of ownership records prior to the Napoleonic Era (prior to 1799), even fewer prior to 1514. There are only 85 families recorded in the Venetian Archives prior to 1514, and all are of noble blood. Unfortunately, the Bassano’s were not one of these noble families recorded. While we will never unequivocally prove this was their original home in Venice, there is overwhelming evidence, such as their coat-of-arms, rates notices, and history notes in the State Archives of Venice.

The actual modern address of the original building (now separated into parts) is 2713, 2714, 2715 and 2715a Calle Dose da Ponte, San Maurizio, Venice, adjacent to the Hotel Dei Dragomanni. The original home is situated on the Grand Canal near the Gritti Palace. This location makes perfect sense considering they served in the Venetian court as musicians, and operated a merchant business as well as their musical instrument manufacturing business. The size, location and opulence of this property is entirely in-keeping with their mansion on Mark Lane, London.

|

Figure 6 – Street view of Bassano Casa, Calle Dose da Ponte, San Maurizio, Venice. |

Figure 7 – Cut side on view of coat-of-arms (Tree of Life) on the front of the building.

Figure 7 – Cut side on view of coat-of-arms (Tree of Life) on the front of the building.

|

Figure 8 – Anthony, Nowell and Andrea Bassano’s 1633 Coat-of-Arms |

The later 1633 coat-of-arms of Anthony, Nowell and Andrea Bassano from the The Visitation of London, Anno Domini 1633, 1634, and 1635, Volume 1 is below.

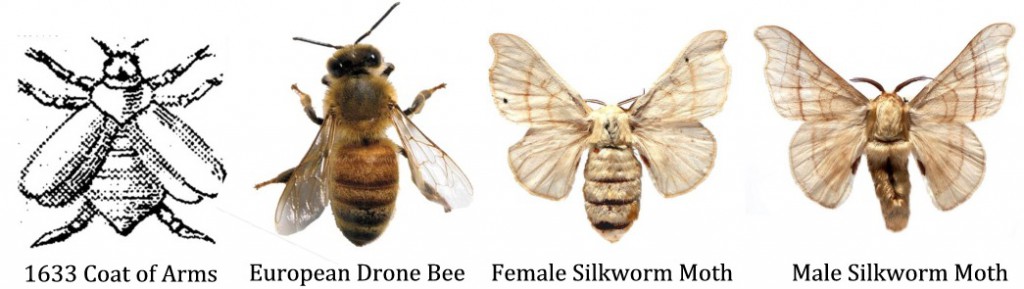

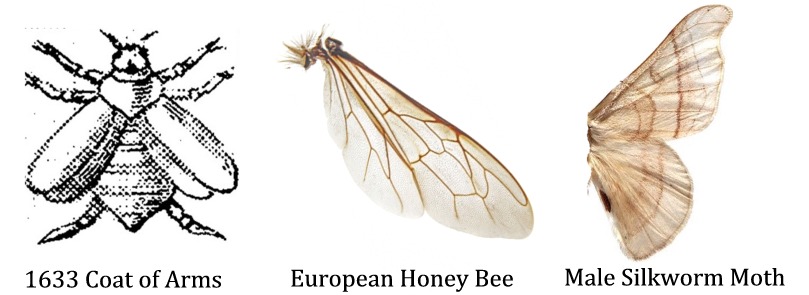

The images of the insects on the 1633 coat-of-arms have been debated for the last four decades. Eleanor Selfridge-Field’s 1979 paper titled ‘Venetian Instrumentalists in England: A Bassano Chronicle (1538-1660)’, contains considerable early information on the Bassano family. Field wrote, “Anthony’s pedigree and arms (three silkworms and a laurel tree) were recorded in the Visitation of London in 1634”, although she admitted the record “is quite incomplete”.[25]

Other scholars have relied upon this publication as fact, and merely reverberated it without examining The Visitation of London, Anno Domini 1633, 1634, and 1635, Volume 1 for themselves. The fact is, The Visitation of London, Anno Domini 1633, 1634, and 1635, Volume 1 does not describe the coat-of-arms in any way, shape, or form; it merely provides the coat-of-arms with the notation: “A scocheon of this Armes produced & is to be justified by Mr Philipot Somsett”.[26] Other than this notation, the entry exhibits details of the heraldry of Anthony Bassano II (1579-1658), Andrea Bassano (1589-1638), and Nowell Bassano (1591-1651), all grandsons of Antonio Bassano I. Thus, modern scholars have simply ‘assumed’ all four are silkworm moths.

If we compare the sketch of the three insects below with the silkworm moth (Bombyx mori) and the European honeybee, we can clearly see the sketch is of European bees as is the case with Antonio Bassano’s 1540 coat-of-arms.

Whilst the striped abdomen of the female silkworm and the honeybee are similar in the sketch, the wings on the sketch are shaped like the honeybee and are attached to the thorax just as the honeybee. The wings of the silkworm moth are an entirely different shape and protrude much higher. The different wing configuration is shown below.

The antennae on the sketch are also like the honeybee, rather than the comb-like feathered antennae of the silkworm moth. On the sketch, there are six legs: four above the wings and two protruding to the rear exactly like the honeybee. Whilst the silkworm moth has six legs, they are entirely covered by their large butterfly styled wings as shown. The eyes in the sketch are also like the honeybee. Therefore, the sketch of the three insects on the 1540 and 1633 depict three honeybees above the Tree of Life.

The Tree of Life is the centrepiece of the 1540 and 1633 coat-of-arms. The tree is not a Laurel Tree (Laurus Nobilis) as previously suggested by Eleanor Selfridge-Field, but it is a Balsam Tree (Balantines aegyptiaca), as exhibited overleaf.

The Balsam Tree is cited numerous times in Antonio Bassano’s 1544 Sefer ha-Refu’ot (Book of Remedies) and throughout the Shakespearean works. The fragrant oil of the Balsam tree has been used since the time of the ancient Israel for religious ceremonies, and also for sexual allurement, making it a valuable commodity amongst the royals.[27] The oil was believed to possess special powers and is still being sold for this purpose today. The Zohar 2:217a, Bereshit Rabbah 62:2 and Ta-anit 25a teach us that thirteen rivers of pure Balsam await the righteous in the world to come.[28]

Turning to the single insect on the crest, it has two dots on the upper wing that may indicate a silkworm moth spinning silk from its abdomen. However, if we examine this sketch side-by-side with European queen bee, its wings, legs, and antennae are like the bee, not the silkworm moth, thus it may well depict the ‘King bee’.

In The Rape of Lucrece, the author refers to ‘I, a drone-like bee’ in reference to losing their honey, speaking of virginity, but also defilement, which Kabbalistically speaking, is losing their state of Da’at, or unity of the spirit to discern and prophesy:

My Honnie lost, and I a Drone-like Bee,

Haue no perfection of my sommer left,

But rob’d and ransak’t by iniurious theft.

In thy weake Hiue a wandring waspe hath crept,

And suck’t the Honnie which thy chast Bee kept.[29]

Emilia Bassano wrote of honeybees in the same way in her 1611 Jewish Essene poetic work of Salve Deus Rex Judæorum (Hail God, King of the Jews):

Blacke as a Raven in her blackest hew;

His lips like skarlet threeds, yet much more sweet

Than is the sweetest hony dropping dew,

Or hony combes, where all the Bees do meet[30]

Aristotle wrote of the ‘King Bee’ (speaking figuratively of the Queen Bee) dying and the whole swarm perishing:

The king bees never leave the hives, either for food or any other purpose, except with the whole swarm; and they say that, if swarms wanders to a distance, they will retrace their steps and return until they find the king by his peculiar scent. They say also that, when the king is unable to fly, he is carried by the swarm; and if he perishes, the whole swarm dies with him.[31]

If we refer to Pausanias, we find the word Jewish ‘Essene’ means a ‘King Bee’. They were the elders in the Essene Church who held priestly roles.[32] This certainly explains why the King Bee (imagery of Jewish Essenes) is atop of the Bassano 1633 coat-of-arms. Pausanias also recorded that the Essenes of Orchomenus were ‘entertainers’ who held annual festivals in the region, which supports my argument, as the Bassano family were the Royal musicians in England for three generations.[33]

It was not until later that the Bassano coat-of-arms was cited or changed in various forms to include butterflies, silkworm moths, and even a griffin from the Short family. The earliest entry was in 1634 when the coat-of-arms of Henry Bassano (of the Presence Chamber to King Charles I) was cited in the Visitations of Essex by Owen and Lilly as ‘butterflies’, although there is no graphic artwork to verify these assertions in the 1634 edition, only the following text:

Arms. – Per chevron vert and argent a leaved branch, slipped of the first, in chief three butterflies displayed as the second, spotted or. [Bassano].

Crest. – A butterfly displayed argent. [Bassano].[34]

Again, this was a herald’s interpretation of the preceding 1633 coat-of-arms of Anthony, Nowell and Andrea Bassano in citing Henry Bassano of the Presence Chamber to King Charles I. It was not until 1729 do we find the usage of three silkworm moths and a mulberry tree in a burial monument of Richard Bassano and family in the Lichfield Cathedral in Staffordshire, which is why modern scholars have assumed the silkworm moth and mulberry tree reflect all generations of Bassanos. The inscription on the monument at Lichfield Cathedral is as follows:

Near this place

Lie the bodies of

Sarah wife of Richard Bassano,

And daughter of Edward Short, of

Meyford in this County, Gent.

She died September 2nd, 1712, aged 67.

Also of John, 3rd son of the said

Richard and Sarah; he died July 27’

1687, aged 9.

Likewise of Mark Anthony,

Eldest Son of Christopher, 4th Son of

The said Richard and Sarah,

Who dies September 4th, 1712; and Richard

Youngest Son of of the said Richard and

Sarah, Vic. Chor. Of this Church,

Who died June 17, 1729, aged 28.

Underneath lieth the body of the first above

Mentioned Richard Bassano,

who dies August 3rd, 1729,

Aged 75.[35]

An image of the monument is below:

Whilst it is difficult to see in the photograph, the three insects now appear as silkworm moths and the insect above resembles a butterfly. The arms were recorded in an 1834 book published by T.G. Lomax titled ‘a Short Account of the Lichfield Cathedral’ as follows:

Per chevron, vert and argent, in chief three silkworm moths, en arriere, and in the base, a branch of a mulberry tree, counterchanged, impaling the arms of Short, azure a Griffin sergeant, argent, betwee three estoiles of eight points, or.

On a wreath, a silkworm moth, argent.[36]

In examining this coat-of-arms we must do so in context of the family in question. Richardus Bassano was four generations after Antonio Bassano, as explained in ‘Link to the Bassanos of Staffordshire and Derbyshire’ below. He was an Englishman in a Freemasonry-dominated business community, where if one was not a Mason, he would not prosper or receive the same stature or rewards as Masons. It was the family lineage of Richardus Bassano that diverged from their Jewish roots and conceded to English Masonry. In fact, his descendants held the position of Worshipful Master of the Derby Lodge in 1805, 1827 and 1829. The mulberry tree, silkworm moth and butterflies are symbols of English Freemasonry, which explains the change from Richardus Bassano of Derby onwards.

Both the silkworm moth and the butterfly are identified as ‘degrees’ by which the metamorphosis takes place, speaking of the transition of enlightenment and immortality in the Freemasonry doctrine. The silkworm moth (Bombyx mori) has a ‘lunar spot’ on the superior wings, which is another Masonic imagery. Then there is the mulberry tree, whereby the silkworm moth consumes its leaves in the pursuit of immortality. The silkworm moth and mulberry tree are so entrenched in Masonry that the 14th song of Master Masons titled ‘The Mulberry Tree’ in the 13th Edition of ‘The Illustrations of Masonry’, cites Masons as attaining immortality, like him, referring to Hiram Abiff, their false Christ.[37] These imageries are contrary to the writing of Antonio and Emilia Bassano, therefore we must conclude Richardus Bassano diverged from their Jewish roots because of mounting pressure in the Masonic dominated business community, and in the end, conceded to English Masonry.

Bassano del Grappa property

I mentioned their Venice dwelling in San Maurizio, but have not yet mentioned what I discovered in Bassano del Grappa. The Council records of Bassano del Grappa show that Jeronimo Bassano resided along Borgo del Lion, which was renamed in the 1950’s as ‘Via Roma’. He lived in a house with a courtyard in the ‘Lion’s Village’ precinct, [38] which ran between the Lion’s statue in Piazza Libertá and the Lion’s Gate situated at the end of Via Roma where a large lion is painted above the city gate. Close to the Lion’s gate, within ‘Lion’s Village’ precinct, there is one and one only existing painted building with an internal courtyard, similar to the London Charterhouse cloister.

The dwelling is located next to the Chiesetta dell’Angelo (Little Church of the Angel), which was built next door in 1655. By the construction methods in the attached brickwork and tower above, the dwelling existed many years prior, possibly up to 300 years prior. Therefore, the construction of this dwelling dates back to the 14th to 15th century. The paintings were applied in the time of Jacopo Bassano, probably during the lifetime of Jacomo Bassano, the musician instrument maker of Bassano del Grappa. He is one in the same brother who returned to England in 1544 after his father Jeronimo Bassano passed away.

On the front of the building, there is evidence of a musical influence, with trumpets, harps, lutes, images of God, ancient philosophers cited in the Shakespearean works, ancient scrolls, and even two emblems of their own coat-of-arms, the Tree of Life.

Right doorpost

Another interesting inscription is the letter that resembles a “H” (Hallel) and “ש” (Hebrew letter Shin) above the doorposts. In the 16th century, Jews would inscribe a symbol similar to a “H” for “Hallel” over their doorposts from Deuteronomy 6:9 as a dedication over their home, business, or Synagogue[39] in a jubilant musical invocation of prayer of blessing, praise, and thanksgiving, normally while singing Psalms 113-118.

The invocation of Psalm 113 is of Spanish origin with a musical performance of the Psalm with song, which calls upon the Archangel ‘Umabel’ (Archangel 61 of the 72 Angels of Shemhamphorash) for favour, travel, and honest pleasures in verse 2;[40] and the Archangel ‘Harahel’ (Angel 59 of the 72 Angels of Shemhamphorash) to brings blessing, governs wealth, printing, and books in verse 3.[41] Psalm 115 calls upon the Archangel ‘Nemamiah’ (Archangel 57 of the 72 Angels of Shemhamphorash) for the deliverance of prisoners, governs great captains, and brings out courage in those in the home.[42] Psalm 116 calls upon the Archangel ‘Chavakiah’ (Archangel 35 of the 72 Angels of Shemhamphorash) to regain favour, peace, love, and loyalty in verse 1;[43] and the Archangel ‘Mumiah’ (Archangel 72 of the 72 Angels of Shemhamphorash) to bring success, health and longevity, particularly for chemistry, alchemy, and medicine in verse 7.[44] This is also interesting in light of Antonio Bassano’s 1544 Sefer ha-Refu’ot (Book of Remedies). This suggests Jeronimo and his sons also practiced medicine from this premises.

Shin is a name of God in the Hebrew, El Shaddai (God Almighty), thus it depicts divine power and divine Archangelic protection with the invocations above. When binding the tefillin on the hand for the priestly blessing, the straps forms the letter shin. Numbers 6:23–27 is recited as a priestly blessing over the home, effectively to ward off evil.[45] Rabbi Abraham Isaac Kook connected this particular shin application to the traditional Kabbalistic interpretation of “black fire engraved on white fire”.[46] This is the exact same Jewish Kabbalistic expression found in Sonnet 131 in regard to slandering creation, which I expound on in Volume 1 of Genesis of the Shakespearean Works:

And to be sure that is not false I sweare

A thousand grones but thinking on thy face,

One on anothers necke do witnesse beare

Thy blacke is fairest in my iudgements place.

In nothing art thou blacke saue in thy deeds,

And thence this slaunder as I thinke proceeds. (Sonnet 131)[47]

These are the very same imageries used by the Bassano family in song, and in many of the Shakespearean plays. The owner of this home was no doubt a Hebrew musician by the imageries and priestly blessings. This home may well be the Bassano’s original home in Bassano del Grappa.

Link to the Bassanos of Staffordshire and Derbyshire

Richard Bassano (1654-1729) of Stone has baffled scholars for the last two centuries. Many claimed that Richard Bassano born in Stone, Staffordshire, in 1654 was not related to the Bassano’s of London. These scholars were misguided in their assumptions. I have traced over 8,000 Bassano family descendants throughout the world. Richard Bassano of Stone, who was named Richardus on his birth entry in 1654, was the son of Richardi Bassano (1605-1669) and Katherine Collier (1621-1696). Richardi Bassano was the son of Anthony Bassano II (1579-1658) and Dorothy Hynd (1581-1649). Anthony Bassano II became a high quality gold ornamented haberdasher in the production of costumes for plays, and for the garments of the wealthy lords of Britain. There are numerous records in Philip Henslowe’s diary to confirm he purchased costumes and musical instruments from the Bassano family.[48] Anthony Bassano II was the son of Arthur Bassano (1547-1624) and Margaret Lothbury (1554-1620). Arthur was the second eldest son of Antonio Bassano I.

It is out of Richardus Bassano (1654-1729) of Stone that the Derbyshire Bassano’s emerged. Richardus’ son Christopher Bassano II (1679-1745) was born in Derby. Christopher named his son Richard Bassano III (1718-1793), who was also of Derby. Richard bore a son and named him Mark Anthony Bassano (1768-1853) after his 4th great uncle, Mark Anthony Bassano (1546-1599), son of Antonio Bassano I.

Other Emblems

The lute is an emblem of the Bassano family, just as the sword of Deborah is. The Hebrew word דְּבוֹרִים (Deborah) means ‘bees’,[49] thus the sword of Deborah is a Kabbalistic imagery of the King Bee, which is also a symbol of the Jewish Essenes. Deborah was the only Old Testament female judge of pre-monarchic Israel, who represented stability by teaching and leading the people of Israel in a time of crisis. The Zohar teaches that Deborah inspired the people to offer themselves to God – to descend to the gates of righteousness.[50] In Deborah’s song in Judges 5, we find her desiring to ‘make music to the Lord’ and in verse 11, Deborah instructs the people to listen to the village musicians:

Listen to the village musicians

gathered at the watering holes.

They recount the righteous victories of the LORD

and the victories of his villagers in Israel.

Then the people of the LORD

marched down to the city gates.

When asked to listen to the village musicians, the Hebrew speaks of going down to the place that water is drawn (centre of the village) and listen to the musicians. The Hebrew word מְחַצְצִים transliterated as ‘mechatztzim’ is cited in the Zohar as a rare word that means archers, singers, musicians or thunder pearls, speaking of the prophetic, but also as dividers, who mediate between the right and left side of the Tree of Life between Hesed and Gevurah.[52] In simple terms, the musician plays and mediates those from a position of judgement (Gevurah) to the love of God (Hesed).

The Bassano family manufactured lutes and beheld three bees on their coat-of-arms overshadowing the Tree of Life, which can be seen as the sword of Deborah and the divine ambrosia that comes when one enters the gates of righteousness in surrender to God.

The Mark

The earliest mark on Hieronymus Bassano’s recorders was identified as “!!” for ease of recognition in text,[53] but these burn marks into the timber recorders were not straight. Whilst most scholars have simply identified the marks as a bee or silkworm moth, I suggest there is far more to it. Below are tracings of these marks under a microscope. Whilst the burn mark on the right may resemble a bee or silkworm moth, the mark on the left does not. To me, these marks look more like glyphs or characters from an alphabet disguised to resemble their emblem.

Whilst they do appear a little like “!!”as most scholars have suggested in the past, if we invert these marks, they appear quite different. While in Venice and Bassano del Grappa recently, I inspected quite a number of 16th century Latin, Greek, Arabic and Hebrew documents. I found some striking similarities between the shape of the Bassano’s mark (glyphs) and the cursive Hebrew letter וֹ (vav). The below image shows two tracings of these burn marks under a microscope on the left, and the Hebrew letter vav on the right. Keep in mind these burn marks are less than 5mm in size, whereas the above has been increased x80 under the microscope. Hebrew and Arabic influences can be seen throughout Venice, and particularly the painted city of Bassano del Grappa.

|

Bassano Recorder Mark, Bassano Lute Mark, Hebrew Letter Vav as a pair (Left to Right). |

Vav (וֹ) is the sixth letter of the Hebrew alphabet. It is often used syntactically as “and”, hence it is recognized as a connector, channel, or bridge. In English we would use the expression, “you and I” will go, hence it is used a connector between men, but also a connector or bridge between God and man. This is why the first five chapters of Genesis nearly all of the sentences (in the Hebrew text) start with vav.

Jewish Kabbalists recognize vav as one of the four letters of the divine name of God (YHVH) and the ten sefirot of the Tree of Life, as explained by Daniel Matt (author of the Zohar, Pritzker Edition, largely based upon Rabbi Isaac Bassano’s 1558-60 Edition of Mantua):

This is the four-letter name: YHVH. Y symbolizes Hokhmah; H, Binah; V includes six sefirot; the final H, Malkhut. Ein Sof (God) is concealed within Keter, while its light spreads through these four letters, from yod to he, from he to vav, from vav to final he.[54]

The Zohar teaches a dream in relation Genesis 2:10, “A river flowed from the land of Eden, watering the garden and then dividing into four branches” where he is the river, yod expands the river on all sides, and vav is a son conceived beneath her. Keep in mind Y is yod, H is he, V is vav, and again H is he from the name of God – YHVH (Yahweh). He sits to be suckled in a relationship depicted by progression or transformation. The royal crown of the sefirot is Keter, which is described by Matt as follows:

The highest crown, Ketei Elyon, is the royal crown, the skull, inside of which is: yod he vav he, path of emanation, sap of the tree, spreading through its arms and branches—like water drenching a tree, which then flourishes.[55]

In essence, vav written twice as a melody is the sweet holy river of God that is the fountain of our lives; it is the flood of grace, a celestial stream that flows into our lives from the Tree of Life – the name of God (YHVH) – in this case through the Bassano’s own musical instruments. If you don’t believe me, then all you need to do is read the below excerpt from Emilia Bassano’s own 1611 tribute to God in Salve Deus Rex Judaeorum (Hail God, King of the Jews):

Sweet holy riuers, pure celestiall springs,

Proceeding from the fountaine of our life;

Swift sugred currents that saluation brings,

Cleare christall streames, purging all sinne and strife,

Faire floods, where souls do bathe their snow-white wings,

Before they flie to true eter[nall] life:

Sweet Nectar and Ambrosia, food of Saints,

Which, whoso tasteth, neuer after faints.[56]

Religion

The earliest record of the Bassano’s Spanish ancestry and Jewish religion can be found in their brief arrest in early 1541 by Henry VIII with other Jewish Spanish and Portuguese musicians called the “Songbirds”. Henry VIII thought Charles V would look favourably upon him as a good Catholic king by arresting and persecuting Jews. A number of Jews were arrested between February and April 1541. However, Henry VIII’s plan backfired, as the King of Portugal wrote in protest to Charles V’s English ambassador, Eustace Chapuys. Henry VIII released the Spanish and Portuguese Jews soon after. The names are believed to be: the Bassano brothers, John Anthony, Anthony Symonds, Peregrine Simon, Anthony Maria, Ambrose Lupo, Francis of Venice, and others.[57]

Please note Ambrose Lupo is mentioned as one of these Spanish Jews arrested with the Bassano brothers. Ambrose Lupo was a Sephardic Jew – a friend of the Bassano family in Venice before London. Records show that Ambrose Lupo was tutored in the Scuola Grande di San Marco by Hieronymus Bassano prior to his death circa 1544, but Ambrose continued in the Scuola Grande di San Marco until 1549.[58] The Scuola Grande di San Marco was a:

Confraternity or lay brotherhood, an assembly of citizens regulated by a constituent rule to carry out charitable and religious work, providing mutual assistance and direct cooperation with the Government of the Republic in support of the great enterprises of the Serenissima, as well as playing an indirect role in the distribution of wealth as a charity.[59]

The scuola has been housed in its current opulent building since 1437 and has gathered many thousands of documents throughout the centuries, many relating to the medical research and practices developed. Ospedale SS Giovanni e Paolo (Venice Hospital) is attached to the rear of the Scuola Grande di San Marco. The historical medical library and the history of Venetian medicine in now displayed in the Scuola.

In the 16th century, the Scuola was a secret Venetian confraternity for charitable and religious work, including sacred musical processions through the streets of Venice to honour the dead with candles.[60] Jeronimo Bassano was known as the Guardian da Mattin, commonly called “Director of Processions” by English scholars, however it means far more. A “mattin” is defined as the morning song of “Songbirds”, which is an interesting connection to the Jewish “Songbirds” where the Bassanos were briefly arrested with others in 1541. The phrase Guardian da Mattin comes from the Guardian of Matuta, an ancient Etruscan goddess of dawn and childbirth, and the patroness of mariners.[61] This is interesting because the Guardian da Mattin is used as imageries in both Hamlet and Macbeth. Jeronimo Bassano could be regarded as a Jewish Guardian of the Ancient Arts.

In Venice, A Guardian da Mattin, or Great Guardian, can be compared to a president or chairman of a board of directors.[62] He was responsible for the entire celebrations, including pageants, plays, and annual festivals such as Carnivale – which is another very interesting connection indeed. Jonathan Glixon in his book ‘Honoring God and the City: Music at the Venetian Confraternities, 1260-1806’, found the Guardian da Mattin was normally elected because of his wealth, power and stature, although not of nobility. [63] This gives us an indication as to how wealthy the Bassano family really were, thereby confirming my earlier assertions in Shakespeare Exhumed: The Bassano Chronicles. As much of the money for these events came from the Guardian da Mattin and other board members, [64] we must deduce that Jeronimo Bassano was a wealthy Jew.

After emigrating to London, Ambrose Lupo’s Venetian born son, Joseph Lupo, married Laura Bassano by 1571 as they are mentioned the ‘Returns of aliens dwelling in the city and suburbs of London from the reign of Henry VIII to that of James I’.[65] Laura was the daughter of Alvise Bassano. Joseph Lupo was denized on 10 December 1601 after application on 19 November 1601. He is cited in the Proceedings of the Commons document of November 1601 as one of the “one of the Queen’s Physitians”,[66] which is interesting considering Jeronimo Bassano was also recorded as a physician in early documents, and Antonio Bassano’s 1544 Sefer ha-Refu’ot (Book of Remedies) contains proven prescriptions, consisting of various elements of nature, particularly tinctures, electuaries, and elixirs (multiplying medicines), with a specific notation that states that a number of healing remedies were ‘proven on Henry VIII’, referring to gout and fistulas of the anus.

As mentioned above, Jeronimo Bassano (Hieronymus de Bassanus) was a famous Master Kabbalist, physician, teacher, musician, and maker of diverse musical instruments in Venezia. He is least recognized today as an author who penned numerous Kabbalistic literary works on Jewish Kabbalah and medicine. His Jewish writings were banned and burnt in 1559 by the Catholic Church as heretical works of Jewish Kabbalah in Index Librorum Prohibitorum of 1559. The entry is under the heading of “de occulta philosophia fy de uanitate scientiarum” whereby the Catholic Church assumed Bassano’s Jewish Kabbalistic literary works were ‘secret (occulta) philosophy and the vanity of science’. Other heretical books banned by the Roman Office of the Inquisition in Index Librorum Prohibitorum of 1559 also include the Thalmud Hebræorum (Babylonian Talmud) and Ars Cabalifica (Techniques of Kabbalah).[67]

One particular book by Hieronymus Bassano was a “comedy [play] written in the vernacular of free will”.[68] Could this comedy of ‘free will’ have been the earliest version of As You Like It? As You Like It is was what we call a ‘pastoral comedy’, which means it involves traipsing around the countryside doing As You Like. Interestingly, As You Like It also contains vernacular prose. This is interesting because both the ‘vernacular’ facet and the title of ‘free will’ to do As You Like are found in one of Hieronymus Bassano’s banned book [of plays] cited in Volume 8 of Index Librorum Prohibitorum of 1559.[69] There was specific mention that it was written in ‘the vernacular’ rather than in the stalwart Latin prose. The dramatist of The Merry Wives of Windsor even taunted early playwrights with “I, you spake in Latten [Latin] then to: but ’tis no matter”, rather than writing in the vernacular.[70] Therefore, it is quite plausible that the earliest version of As You Like It was penned by Hieronymus Bassano prior to 1544.

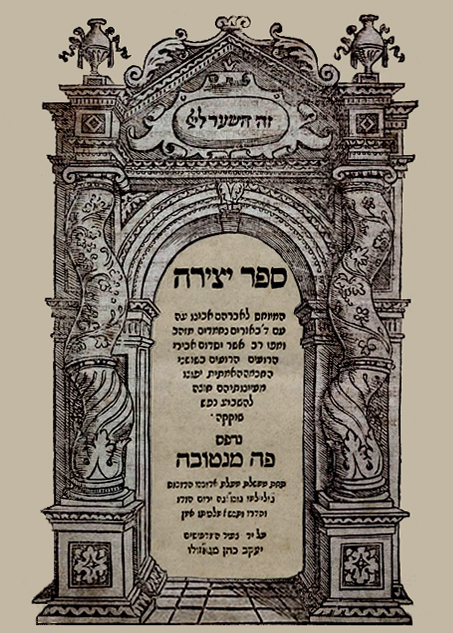

Much of the same Jewish Kabbalistic teaching is found in the Zohar and in Antonio Bassano’s 1544 Sefer ha-Refu’ot (Book of Remedies) which references the angel ‘Azarie’ as the Archangel ‘Raphael’ who is noted as being ‘in charge of healing the wounds of the sons of men’. Such Kabbalistic imageries are used right throughout the Shakespearean works. In The Tempest, the Jewish Essene angel of fire, Ariel,[71] is used as one of the four elements from the Sefer Yetzirah (The Book of Formation) in relation to creation. The Sefer Yetzirah was penned during the time of Yehudah ha Nasi (Elena Bassano’s ancestor) as Chief Priest of the Sanhedrin. The angel Ariel is mentioned in Isaiah 29:1-7 as the personification of Jerusalem, like a ghost that shall whisper out of the dust and turn a multitude of tyrants into chaff.

Emilia Bassano-Lanier’s own writings were also filled with Jewish Kabbalistic imageries, but this subject could fill many volumes. Instead, I will focus upon one interesting record that reveals who Emilia really was, and that is Simon Forman’s diary. Emilia consulted the astrologer between 1597 and 1600 regarding relationships, fortune, trust issues, and also discussed the invocation of spirits. Gamble noted Forman’s reminder to investigate “Lanier’s tales of invoking spirits” and how she had succeeded to summon an ‘incubus’ or ‘succubus’ (Lilith in Jewish Kabbalah).[72] Forman’s actual notation in his diary of Emilia’s intent to invoke villainy is as follows:

at 5 pm 7 Jani. Monday. to know whi mrs Lanier sent for me et quid inde sequitur {et} wher she Entendes Any mor villani/ or noe.

This is a combination of Latin and Early Modern English. It can be translated as:

Attended at 5 pm on Monday 7 January 1600, to know why Mrs Lanier sent for me, and what from this follows, whether she intends any more villany or not.

In essence, Emilia claimed that she had mastered the art of practical Kabbalah in invoking, praying or appealing to angels, who will carry our messages and pleas to God (angelology), and the art of demonology by “invoking demonic spirits”. Before you assume Emilia was an occultist, in Emilia’s Salve Deus Rex Judæorum, she wrote a tribute to Christ as an alternate Epistle to Paul in the Bible, and in that same volume she wrote of “blessed Angels, powrefull Spirits” and “If God by prayers had an army sent Of powrefull Angels, who could them prevent?” Let us not forget that Jesus commanded demons, as did the Apostles. However, the Christian Church in recent times have lost the power of God because too many Pastors misinterpret Scripture, particularly Matthew 26:53, where they refuse to acknowledge they hold power over demons. The fact that demons are actually angels that rebelled, is why Kabbalists believe they have power over both angels and demons.

We do know that members of the Bassano family possessed many banned Jewish Kabbalistic books prior to at least 1577, because during the Venetian inquisition of Orazio Cogno on 27 August 1577, Cogno was asked who in England wanted you to read prohibited books and teach the doctrine of heretics (Jewish books of Kabbalah). He replied:

Ambroso da Venezia (Ambrose Lupo) who is a music player (or musician) of the Queen of England; he has two children and has got married there, even though, as I have heard, his wife lives here in Venice and, so they also say, he used to send money to her. And there are also five Venetian brothers who are musicians of the Queen and play the flute and the viola (Bassano’s); and there is a Venetian gentlewoman from Ca’ Malipiero who has a school and teaches reading and the Italian language; and I don’t know of anyone else.[73]

It is clear from this entry that the Bassano family still possessed copies of these Jewish Kabbalistic books in 1577, some years after the Index Librorum Prohibitorum of 1559, and taught according to the ancient Schools of the Essenes (Yahad – evangelism – to become a Jew, from Esther 8:17).

The Bassanos embraced the ancient Jewish Essene doctrine of angelology and demonology. They were not occultists – there is a vast difference between consultation of demons, sorcery and magic (Occultists), and the command of demons through Scripture (Jewish Essenes). The Jewish Essenes were the forerunners of Christianity – Jesus Christ was not a Pharisee, nor a Sadducee, but an Essene, hence the confusion with some scholars claiming the Bassanos were Jews and others Christians. By their own writings, the Bassano family were unmistakably Jewish Kabbalists who embraced Essene doctrine and taught according to the ancient Schools of the Essenes.

Bassano Graves in Jewish Cemetery

The fact that 19 descendants of Giacomo (Jacomo) are buried in the old Jewish Cemetery of Venice (San Nicolò on the Lido), 14 of which I managed to locate, confirms the family were Jewish. Without proving a “true Hebrew” heritage, one simply cannot be buried in a that particular Jewish cemetery. As mentioned above, some tombstones are inscribed in Italian and some are in Hebrew. The Hebrew surname is spelt various ways, including הַבָּשָׁן (de Bassan), בסני (Bassani), and one of the earliest tombstones is בסנו (Bassano), with one exhibiting the Tree of Life above – the coat-of-arms of the Bassano family.

Interestingly, upon inspection of all the Christian cemeteries in Bassano del Grappa and Crespano del Grappa, there were no tombstones of any Bassano family member prior to the 19th century, despite earlier graves being preserved intact. Admittedly, some could have been destroyed. One explanation regarding the lease of land in Crespano may well have been for a family burial ground in true Hebrew tradition, however I have not been able to locate any tombstones for the Bassano family on this Church land, but they may have been bulldozed like many early Jewish graves in Venezia.

At this time, the only preserved graves of the Bassano family prior to the 19th century are in the old Jewish Cemetery of Venice (San Nicolò on the Lido). The only Jewish cemetery in Venezia from 1386 AD was the Jewish Cemetery on Lido. Over time, the cemetery was neglected and many tombstones have been pushed over or buried. The World Monuments Fund have been assisting with funding the restoration of the Cemetery since 1994. There is a long way to go. If you can help, please do? We may yet uncover the other 5 tombstones in the future.

I conclude the Bassano family were true Hebrew Jewish Masters of Kabbalah who embraced many of the ancient Jewish Essene doctrines. They were not Christian, nor Muslim (Moors).

______________________________________

As a final note, I am yet to find any of the prohibited books by Jeronimo Bassano in existence today. I have searched every known historic bookstore and library in Venice, Bassano del Grappa, Rome and London, and there is simply no trace of any surviving copy. We do know that copies survived the 1559 Index Librorum Prohibitorum in England, and some may still exist within the Vatican archives. Whilst I am a Minister, I was not permitted into the Vatican archives. If you are part of the Vatican staff archives, or are possession of, or know of any literary work of Hieronymus de Bassanus (Jeronimo Bassano) in existence today, please contact me?

______________________________________

For further information on the Bassano family and their connection to the Shakespearean works, please read my major academic work of ‘Genesis of the Shakespearean Works’. More information is also available on my website at www.petermatthews.com.au, or you can like my Facebook page to keep abreast of any updated material I find. My academia profile is also available here.

[1] Bible Hub: Strong’s Concordance: 1316 Bashan, http://biblehub.com/hebrew/1316.htm

[2] Bible Hub:Strong’s Concordance: 931 basanos, http://biblehub.com/greek/931.htm

[3] Prior, Roger; Lasocki, David (1998), The Bassanos: Venetian Musicians and Instrument Makers in England, 1535-1665, Ashgate, p4.

[4] Henry VIII: June 1534, 26-30, Letters and Papers, Foreign and Domestic, Henry VIII, Volume 7: 1534 (1883), pp. 326-357.

[5] Actual Christiening Record: “Emillia Baptist bapt ye 27 of January” (1569).

[6] Letters and Papers: October 1539, 1-5, Letters and Papers, Foreign and Domestic, Henry VIII, Volume 14 Part 2: August-December 1539 (1895), pp. 102-108.

[7] Henry VIII: April 1540, 21-30, Letters and Papers, Foreign and Domestic, Henry VIII, Volume 15: 1540 (1896), pp. 251-300.

[8] Bassano, Antonio (1544) Sefer ha-Refu’ot (Book of Remedies), p1.

[9] Henry VIII: April 1545, 26-30, Letters and Papers, Foreign and Domestic, Henry VIII, Volume 20 Part 1: January-July 1545 (1905), pp. 278-329.

[10] Maskell, Joseph (1864) Collections in Illustration of the Parochial History and Antiquities in the City of London, Bryan Corcoran & Co, Mark Lane, London, http://archive.org/stream/berkyngechirchej00maskuoft/berkyngechirchej00maskuoft_djvu.txt

[11] Queen Elizabeth – Volume 181: August 1585, Calendar of State Papers Domestic: Elizabeth, 1581-90 (1865), pp. 256-265.

[12] Ruffatti, Alessio (1998) La Famiglia Piva-Bassano Nei Document Degli Archevi Di Bassano Del Grappa, Musica e Storia, VI, p351.

[13] In the Museo Civico of Bassano Del Grappa, there are protohistoric exhibits in bronze (small statues), one depicting the attacking Hercules. It was found near Bassano, buried on the ancient road over the mountain, adjacent the Brenta River in Cismon Del Grappa. It is dated 4th – 1st century BC.

[14] Homer’s Illiad 4:104. http://www.perseus.tufts.edu/hopper/text?doc=Perseus%3Atext%3A1999.01.0134%3Abook%3D4%3Acard%3D1

[15] F1, AYL 4.3.2154-60.

[16] Ruffatti, Alessio (1998) La Famiglia Piva-Bassano Nei Document Degli Archevi Di Bassano Del Grappa, Musica e Storia, VI, p351.

[17] Letters and Papers: October 1539, 1-5, Letters and Papers, Foreign and Domestic, Henry VIII, Volume 14 Part 2: August-December 1539 (1895), pp. 102-108.

[18] Letters and Papers: Letters and Papers (1552) Foreign and Domestic, Henry VIII, Volume 6, C4/8/1/2 from GB-Lpro cited by Lasocki page 14, ref 46.

[19] Wise, Leonard F., edited by Hansen, Mark, (1967) Kings, Rulers & Statesmen, reprinted 2005, Sterling Publishing Company, New York, p. 185.

[20] Barberino Latino 5205, f. 15r. Case?MS/6a/34, f. 19, cited in Grendler, Paul F (2015), The Roman Inquisition and the Venetian Press, 1540-1605, Princeton University Press, p213.

[21] Heller, Marvin J (2010), The Seventeenth Century Hebrew Book (2 Vols), Brill, p679.

[22] Strong’s Concordance: 1847, daath, http://biblehub.com/hebrew/1847.htm

[23] Dubov, Rabbi Nissan Dovid (2011) Deeper Reality, http://www.chabad.org/library/article_cdo/aid/361899/jewish/Deeper-Reality.htm

[24] Most historians recognize “ancient” as prior to the fall of the Roman Empire in 476AD. By the age of the building, it is most likely late 13th to late 15th century construction.

[25] Selfridge-Field, Eleanor (1979), Venetian Instrumentalists in England: A Bassano Chronicle (1538-1660), Leo S. Olschki, Ed. Firenze, p184

[26] Saint-Geoge, Sir Henry and Sir Richard (1880), The Visitation of London, Anno Domini 1633, 1634, and 1635, Volume 1, Harleian Society, p54.

[27] JewishEncylcopedia.com: Balsam, The unedited full text of the 1906 Jewish Encyclopaedia, www.jewishencyclopaedia.com

[28] Matt, Daniel (2002-2014), The Zohar, Pritzker Edition, Stanford University Press, Volume 5, 2:127a, pp. 192-3.

[29] Q1, Luc. L836-40.

[30] Bassano (Lanyer), Emilia (1611), SALVE DEVS REX IVDÆORVM, Richard Bonian, a free copy of the works can be found in the Reasscence Editions, University of Oregon, http://darkwing.uoregon.edu/~rbear/lanyer1.html

[31] Aristotle, Book v, Ch 18-19. From the behaviour of honeybees by Lambros Tsounis, http://www.greenapple.gr/articlesdesc.php?id=556

[32] Ransome, Hilda (2012), The Sacred Bee in Ancient Times and Folklore, Courier Corporation, ISBN 9780486122984, p58.

[33] Pausanias, 8.13.1.

[34] Harleian Society (1878), The Publications of the Harleian Society, Volume 13: Visitations of Essex, 1634: Bassano, p344-5.

[35] Lomax (1834), A Short Account of Lichfield Cathedral, Printed and sold by T.G. Lomax, p54.

[36] Ibid.

[37] Preston, William (1821), Illustrations of Masonry, 13th Edition, G & W.B. Whittaker, p425.

[38] Ruffatti, Alessio (1998) La Famiglia Piva-Bassano Nei Document Degli Archevi Di Bassano Del Grappa, Musica e Storia, VI, p356. Translation by Peter Matthews.

[39] Cumming, James H (2011), Torah Nondualism: Diversity, Conflict, and Synthesis in the Pentateuch: The Letter Shin. http://quastler.com/id33.html

[40] The 72 Names (Angels) of God: Umabel. http://guideangel.com/61.html

[41] The 72 Names (Angels) of God: Harahel. http://guideangel.com/59.html

[42] The 72 Names (Angels) of God: Nemamiah. http://guideangel.com/57.html

[43] The 72 Names (Angels) of God: Chavakiah. http://guideangel.com/35.html

[44] The 72 Names (Angels) of God: Mumiah. http://guideangel.com/72.html

[45] Cumming, James H (2011), Torah Nondualism: Diversity, Conflict, and Synthesis in the Pentateuch: The Letter Shin. http://quastler.com/id33.html

[46] Ibid.

[47] Q1, Son 131:1960-5.

[48] Rutter, Carol Chillington, ed. (1999) Documents of the Rose Playhouse, Manchester University Press.

[49] Strong’s Concordance: 1682 – Deborah, The Lockman Foundation. http://biblehub.com/hebrew/1682.htm

[50] Matt, Daniel (2002-2014), The Zohar, Pritzker Edition, Stanford University Press, Sections 1:32(a-b) in Vol 1, pp. 196-7.

[51] Judges 5:11 New Living Translation.

[52] Matt, Daniel (2002-2014), The Zohar, Pritzker Edition, Stanford University Press, Sections 1:32(a-b) in Vol 1, p196.

[53] Lyndon-Jones, Maggie (1996) Who was HIE.S/HIER.S/HIERO.S?, FoMRHI #083 Bulletin April 1996, The Fellowship of Makers and Researchers of Historical Instruments, Oxford, UK.

[54] Matt, Daniel C (1995), The Essential Kabbalah: Heart of Jewish Mysticism, Castle Books, p2. http://www.shadowsgovernment.com/shadows-library/Matt,%20Daniel%20C%20-%20The%20Essential%20Kabbalah%20%5Bpdf%5D.pdf

[55] Matt, Daniel C (1995), The Essential Kabbalah: Heart of Jewish Mysticism, Castle Books, p25. http://www.shadowsgovernment.com/shadows-library/Matt,%20Daniel%20C%20-%20The%20Essential%20Kabbalah%20%5Bpdf%5D.pdf

[56] Bassano (Lanyer), Emilia (1611), SALVE DEVS REX IVDÆORVM, Richard Bonian, a free copy of the works can be found in the Reasscence Editions, University of Oregon, http://darkwing.uoregon.edu/~rbear/lanyer1.html

[57] Prior, Roger (1983), Jewish Musicians at the Tudor Court, Musical Quarterly 69, pp. 253-65. Also refer Ian Lancashire’s 1984 ‘Records of an English Drama’ and records in Letters and Papers, Foreign and Domestic, Henry VIII, Volumes 16 & 17, 1541-2.

[58] See various records in the Scuola Grande di San Marco.

[59] Scuola Grande di San Marco: Art and History

[60] Glixon, Jonathan (2003), Honoring God and the City: Music at the Venetian Confraternities 1260-1806, Oxford University Press, UK, p106.

[61] Mater Matuta National Achaelogical Museum, Florence. https://www.researchgate.net/figure/283791294_fig7_Figure-9-Unknown-Etruscan-art-5th-c-BCE-Mater-Matuta-National-Archaeological-Museum

[62] Scuola Grade: Scuole Grandi e Piccole a Venezia, in definitions and explanations half way down the page. http://www.scuolasangiovanni.it/index.php?page=14¶meter=scuole_grandi_e_piccole

[63] Glixon, Jonathan (2003), Honoring God and the City: Music at the Venetian Confraternities 1260-1806, Oxford University Press, UK, p48.

[64] Ibid.

[65] Returns of aliens dwelling in the city and suburbs of London from the reign of Henry VIII to that of James I, I.434, www. familysearch.org

[66] Proceedings in the Commons, 1601: November 16th – 20th, Historical Collections: or, An exact Account of the Proceedings of the Four last Parliaments of Q. Elizabeth (1680), pp. 216-236.

[67] Index Librorum Prohibitorum (Index of Prohibited Books from the Roman Office of the Inquisition), 1559.

[68] Ibid.

[69] Volume 8 of the Index de Rome: 1557, 1559, 1564, Compiled by Rene Davignon and Ela Stanek (1990) ISBN 9782762200553, Translated by Dr Peter D Matthews, Entry 392, p494.

[70] F1, Wiv. 1.1.166-7.

[71] Webster, Richard (2009), Encyclopedia of Angels, Llewellyn Worldwide, ISBN 9780738714622, p21.

[72] Gamble, C.W.H.(2011), Shake-speare’s “Mr W.H.”, the “Dark Lady” and the “Lovely Boy”, The Marlowe Society Research Journal – Volume 08 – 2011, p10. http://www.marlowe-society.org/pubs/journal/downloads/rj08articles/jl08_01_gamble_mr_wh.pdf

[73] Testimony of Orazio Cogno before the Venice Inquisition on August 27th, 1577, translated by Dr Noemi Magri of the Shakespeare Oxford Fellowship.

The time you took to illuminate this part of our shared ancestry means more than I can express.

It has freed me and I have the feeling you know that same feeling.