To Download a PDF copy of this paper, please click on the link below, as it is easier to read and is fully referenced:

Abstract

This is a working draft paper, based upon my major academic work of A Comprehensive Commentary of Shake-speares Sonnets in three tomes, the first published in December 2020. I have spent a lifetime in the Shakespearean works, and nineteen years now researching the Sonnets. I discovered what no other scholar on the planet has managed to find ― the real Aramaic, Hebrew, Greek, Latin and Italian sources used by the poet. We have finally been able to offer real explanations as to who wrote the Sonnets, their religion, why they wrote the Sonnets, and a graphic walk through the poet’s ancestry throughout the ages. The multi-layered Zoharic שיר זהב (Shir Zahav, golden poems) are comparable to the great Kabbalist Rabbi Isaac Luria, investigating ‘Bat Torah’ (Women of Torah) — the prominent Dark Ladies of the Bible involved in the redemption of Israel — Lilith, Eve, Naamah, and Tamar.[1] I have decoded all of the poet’s Hebrew and Aramaic ‘secret codes’ on cosmology, the nature of the soul, the afterlife, the angelic realm, eschatology, the erotic aspects of the feminine Divine, and the prophetic Dark Lady Sonnets on the Age of the Woman we have recently entered into on 29 November 2020…[2] revealing some astonishing prophecies for the 21st to the 23rd centuries. This paper investigates some of these imageries and their origins. I dedicate this paper to Donna Matthews, granddaughter of Ada Goodwin-Bassano. One of my academic friends suggested I publish a working paper to offer some new information with facts that can “begin a process to attempt to understand” this deep theological work of the Sonnets.

Historical Background

Shake-speares Sonnets are 154 consecutive poems first published in quarto edition on 20 May 1609 by Thomas Thorpe, which was entered into the Stationers’ register as “a Booke called Shakespeares sonnettes”. On the front cover, the title is displayed, “SHAKE-SPEARES SONNETS” with the caption, “never before imprinted”. Like the copyright laws today, every new book published in England to be registered at Stationers’ Hall and sent to the Bodleian Library to protect themselves from Copyright infringements. We have no idea how many copies of the Sonnets were printed in 1609, though there are at least thirteen known extant copies in existence today. There may well be others in private collections.

The original sale price of the Sonnets was one shilling, which was quite expensive for a quarto edition. A quarto book is formed from folding a sheet of printing paper folded into four, rather than two for a folio edition. The condition of the thirteen copies is surprisingly pristine, suggesting the Sonnets were not popular in their day.

When the Sonnets were published, the Scottish King James I of England was on the throne, and Anne of Denmark was his Queen. Anne was a strong noble woman of power, principle, and a patron of poets, playwrights, and performers. Unfortunately, earlier historians relied on the ramblings of her husband, who called her “weak and a tool in the hands of clever and unscrupulous persons”. Had they read the remarks of the Venetian ambassador to the Doge of Venice, they would have learned: “She is intelligent and prudent; and knows the disorders of the government, in which she has no part, though many hold that as the King is most devoted to her, she might play as large a role as she wished”. I believe Queen Anne became an ambassador for women in England, who stood opposed to her husband.

Early 17th century England was a very different period, where many women were forbidden to read by their husbands, instead forthrightly told they are to dedicate their time to the needs of the husband and their children. Many modern scholars depict the unoccupied wife in this period as one with desire, love, and sex on their minds. Having read many of the early women writers during this period, I discovered they were not preoccupied with sex at all; this was the mannerism of the predominantly male authors. Women raised in wealthy homes were consumed with piety, beauty, ethics, wisdom, fortitude, and honour, where their sonnets, poetry, and plays were their means of expressing themselves. After the Black Death (Bubonic Plague) in 1563 and 1593, with more than 18,000 deaths in London, entering the 17th century was a turbulent time with poverty and hunger for those less privileged, and the majority could not afford an education.

Elizabeth Carey, Viscountess Falkland (1585–1639), was the first woman in England to have an original play in English published in her own name. Elizabeth was the wife of Henry Carey, 1st Viscount Falkland (1575-1633), descendant of Sir William Carey (b.1436 of Cockington), who was also the ancestor of Henry Carey, 1st Baron Hunsdon (1526-1596). Elizabeth was a keen theologian and philosopher, fluent in Spanish, Italian, Latin, Hebrew, and Transylvanian. It was a time of change, where early 17th century London was filled with doating poets and potential playwrights, all vying to earn the patronage of a high and lofty, self-absorbed king, or his noble and intelligent queen.

King James I was a king without parents to guide him, disturbed by his father’s execution in 1567, and his mother’s incarceration and subsequent execution in 1587. One of the major sources of the play Macbeth was King James’ own 1597 book titled Daemonologie, based upon the detailed witch trials of 1590 published in News from Scotland. This book demonized ordinary God-fearing women who prophesied as being necromancers — commanders of black and unlawful science of magic. If there was any suggestion a female teacher taught on the “light” of God in school or Sunday School, it could easily be misconstrued as consulting Lucifer, not realizing Jesus said, “I am the light of the world. If you follow me, you won’t have to walk in darkness, because you will have the light that leads to life” (John 8:12). It was a dark time, and many brought light into the world through their poetry, plays, and masque

Rowse’s Dark Lady

On Saturday, 5 May 1973, Alfred W. Rowse published an article in the Aberdeen Press and Journal, claiming Emilia Bassano was the Dark Lady of the Sonnets, alluding to her promiscuity with the words: “a bad lot” who “with Shakespeare, inspired the famous and often tortured Dark Lady sonnets”. In a following article published in the Newcastle Journal on Saturday, 6 April 1974, Rowse claimed the Dark Lady, “that has puzzled millions of schoolboys and thousands of scholars” was none other than Emilia Bassano, simply because he could not properly translate the diary notes of a sexual predator named Simon Forman. Rowse wrote:

Nothing was known of Emilia Bassano, later Mistress Lanier, until Simon Forman told us she was, in his voluminous and invaluable casebooks in the Bodleian Library. She had been the mistress of Lord Chamberlain Hunsdon, the Patron of Shakespeare’s Company, until she was discarded and married off to the musician Lanier in October 1592. That gave me my clue.

In truth, a Mistress in

that period was a woman who held the position of: head of a household, or in

charge of a school, in charge of servants, or a female scholar — it is Middle English

word from Old French Maistresse and Maistre (Master), meaning the female equivalent of a Master in their field of expertise. Unfortunately, Rowse has tainted many researchers over the past forty-five years, evidenced by Paul Kauffmann writing the following in 2017:

Nine eminent scholars, historians, and directors have concluded that between 1592 and 1594 William Shakespeare, aged twenty-eight, and Emilia Bassano-Lanier, aged twenty-three, referred to as the “Dark Lady,” had a sexual relationship which Shakespeare described in his sonnets… Bassano-Lanier is the best candidate for the Dark Lady. She had the means and the motive to help him write “immortal lines to time”, as inspirer, translator, and expositor, rather than as “joint-author”.

I have forensically examined and translated the ten entries Forman made about Emilia Bassano-Lanier. Unfortunately, many modern scholars have vilified Emilia as a promiscuous woman because Rowse claimed she committed adultery with William Shakespeare. His evidence was entirely circumstantial, based upon the diary notes of a sexual predator named Simon Forman, who recorded at 11:00am on 10 September 1597 that inter alia “I go to Lanier (noted as star sign ♄ Saturn, remembering he is an astrologist) this night or tomorrow where husband (Alfonso, patient 2824) will Px (Prognosis) me, and nō & where I shall be welcome & halek (sex)”. Emilia had been married for almost five years to Alfonso Lanier, who was the son of Emilia’s first cousin, Lucretia Bassano, and her husband Nicholas Lanier. Lucretia was Antonio Bassano’s daughter. Antonio Bassano married Elena de Nasi, one of the descendants of the royal lineage of the Jewish Nasi family. I have provided a basic family tree to the rear showing Antonio, John, and Baptista Bassano were sons of Jeronimo and Hebbe Bassano, his second wife, believed to be of dark skin.

Forman was well aware of the marriage because Emilia revealed her name was Emilia Bassano on 17 May 1597 (four months earlier): “to have been married for colour”. Alfonso Lanier Forman’s diary note for 6:00pm on the following day 11 September 1597 tells us that it was merely an appointment for later that evening:

the 11 Septm ☉ p m’ at on Best to send to mrs Lanier to se wher she will byd me com’ to her or noe or what will com of it/.

Rowse should have realized the symbol ☉ means the “sun”, which refers to Jacob, Christ, Israel, the number 6 in Kabbalah, but it also refers to the healing fruit of “balsam” used to make ointment. This means at 6pm on the evening of 11 September 1597, Forman records that he did bring dried balsam fruit, was welcomed, stayed all night (well after dark), but could not have sex. Emilia rejected the sexual predator Simon Forman. Had Rowse investigated the further records, he would have found Alfonso had been unwell since at least 3 June 1597, where Emilia was caring for him four months, while she had a child at foot to Henry Lanier, and was in the early stages of pregnancy with another baby. This was mere invention by male scholars to fit their ideals. Emilia did not have relations with Simon Forman. Now let us investigate whether she relations with William Shakespeare.

Shakespeare in Willobie His Avisa

John Hudson was one of the closest scholars to ever research the Sonnets; He was also able to determine there was a connection between the Sonnets, Salve Deus Rex Judæorum (Hail God, King of the Jews) by Emilia Bassano, and the long narrative poem Willobie His Avisa, which includes William Shakspeare and the Lord Chamberlain, Henry Carey.

Willobie His Avisa is signed October 1593, therefore it was probably written between February and October 1593 during the time the playhouses were shut. It was published under the pseudonym Hadrian Dorrell as Emilia Bassano, the most likely candidate, admitted publishing it “without his consent” from the hand of Henry Willobie. It was entered into the Stationers’ Register on 3 September 1594 by John Windet at Cross Keyes. Willobie His Avisa is a poetic work on the evil disposed men (“seuerall dispositions”) and the chastity of women, interestingly sources as Salve Deus Rex Judæorum and the Sonnets, with some citations from John Florio’s 1591 collection of Italian Proverbs titled: Garden of Recreation, to throw Henry Wriothesley, 3rd Earl of Southampton, off the scent, because he could have prevented it from being published.

Most scholars presume Henry Willobie did write the poetic work, and died soon after graduating from Exeter College, Oxford, on 28 February 1594, though his death record shows he was buried on 25 February 1593 at St. Botolph Aldgate, London, England, for the other Henry Willoughby of Wiltshire who died in 1596, previously recognized as the poet, was only 2 years of age upon death. Henry Willobie cannot be the poet, having died prematurely in February 1593, though he was the perfect cover to publish Emilia’s scathing true story.

Upon finding his burial records in the Parish Register of St Botolph’s, Aldgate, I found Henry Willobie was working as a tapster (barmen), living alone at the former home of Samuel Powell, a broker, dwelling at the sign of King David. Henry Willobie had no surviving wife, just as the poet revealed. This “Tapster” is perfectly preserved in the early 1594 Quarto Edition of The Taming of a Shrew, along with Emilia (Bassano), Alfonso (Lanier), her sister as Kate, William Shakespeare as Christopher Slie (his mother’s real life brother-in-law was named Thomas Sly of Lapworth), the drunker tinker who was conned into thinking he was a Lord by the Tapster, who said to Shakespeare, “I marry but you had best get you home for your wife will courie (snuggle) you for dreaming here to night”, and instead the Tapster went home with William Shakespeare! It was entered in the Stationers’ Register as “A Shrew” on 2 May 1594, probably also penned during 1593. The Tapster is cited as a “Host” in the 1623 First Folio Edition after Shakespeare’s death.

Now to connect this to Willobie His Avisa. The main character is a woman (Isabella, or Avisa in Spanish), Countess of Gloucester, wife of King John) overlaid upon herself (Emilia Bassano), being beset upon by a myriad of competing suitors, all of whom she rejected because of her deep faith in God: Juno who she called a “filthy beast” that “came to give her wealth…great riches” and Old Helicon, the Patron of England’s Helicon, Henrico Willobego [not Henry Willobie], referring to Henry Carey, the real patron of Lord Chamberlain’s Men, who in the work is associated with William Shakespeare. Emilia named Carey “a Devil Old” that lived in a Castle, dropping the play name “Love’s Labour’s Lost” (Labours Lost), friend of “W.S.” (William Shakespeare) that turned from Comedy to Tragedy where “another could play his part better than himself”. In Canto 1, we find Emilia tells of how these suitors tried for ten years: “wanton love hath had a fall, ten yeares haue tryde this constant dame” until “Her Sire the Maior of the towne” for the Mayor of London at that time was Sir William Rowe Lord, who died on 23 October 1593, the very same month Willobie His Avisa is dated. Is this a coincidence? I doubt it.

The nature of relationship between Henry Carey and William Shakespeare is revealed in Canto 44, where we find Carey had a “secret disease” of the prostate, assisted by Shakespeare. The “secresy of his disease vnto his familiar frend (intimate friend) W. S. who not long before had tryed the curtesy of the like passion” alluding to Shakespeare’s bisexuality. The issue arose between Carey, Shakespeare, and Emilia, because W.S. blamed Emilia for the disease, where he asked Carey, “Tell what she is that witch’t thee so, I sweare it shall no farder go”. Soon after in the story, Shakespeare talked with H.W. (assumed to be Henry Wriothesley, 3rd Earl of Southampton), who violently assaulted her after the recommendation from W.S. to use all forms of persuasion: “I thinke in tyme she may be wonne”.

Had scholars connected “there did the Rose and Lillie lie, that brauely deckt a smiling face” (the Rose of Israel) from Willobie His Avisa with the Sonnets, they would have realized Emilia wrote both works. The Spanish name “Avisa” is translated to Hebrew as לְהַזהִיר (“to warn”) in the same way she warns us of the need for purity to enter heaven, which is an underlying theme in the Sonnets and Salve Deus Rex Judæorum. Emilia wrote in the same language and tone in all three volumes, desiring to protect the chastity of women so that all women are not sullied by “evil disposed men”. In Willobie His Avisa, Emilia told her real-life real story over the tale of Isabella, adding the Latin phrase “Amans Vxor Inuiolata Semper Amanda” for the name “Avisa” that she translates as “A loving wife, that never violated her faith, is always to be beloved” not wanting to give away her Hebrew origin, which comes from, “A vertuous woman is the crown of her husband, but she that makes him ashamed, is as corruption in his bones” (Proverbs 12: 4), referring to the sullied maidens, who have no share in the World to Come.

In Willobie His Avisa, the poet noted the rape of “Brytaine Lucretia, or an English Susanna”, because both women are mentioned in Emilia’s Salve: “Twas Beautie made chaste Lucrece loose her life” and she cited “the unjust Judges, by the innocency of chast Susanna”. Emilia revealed how she was beaten by H.W. by smarting (slapping, beating) her face in a “fierce assault” after she rejected him. For those scholars who do not understand the meaning of “chast”, the Oxford Languages Dictionary defines it as: “abstaining from extramarital, or from all, sexual intercourse”. How in the world could anyone deem that promiscuous? Emilia admitted that she spent twenty years telling noble men with vile thoughts, “Hand off my Lord… I’le neuer yeeld, I’le rather die”. Emilia clearly did not have sexual relations with William Shakespeare, though the evidence points towards Shakespeare having a homosexual relationship with the Lord Chamberlain, Henry Carey.

Connection between the Sonnets and Salve, Revealing the True Title

Had scholars researched Emilia’s work, they would have found Emilia attacked Shakespeare’s credibility (the Swan) as being “insignificant”, who would die, “with his fair corps, when ‘twas by death imbrac’d” (dead and stay dead), juxtaposed against the ascended Christ in Salve Deus Rex Judæorum (Hail God, King of the Jews):

No Dove, no Swan, no Iv’rie could compare With this fair corps, when ‘twas by death imbrac’d; No rose, nor no vermillion halfe so faire As was that pretious blood that interlac’d His body, which bright Angels did attend, Waiting on him that must to Heaven ascend.

Had they delved a little deeper, they would have noticed that Emilia hid the connection between the two works within Salve, claiming the ‘holy Sonnets’, which are in essence a commentary of the ancient holy Zoharic texts, depicting the “most lovely Lady” Adonai (the ‘Dark Lady’), with the “sweet harmony” of music, referring to Sonnet 8:

Of great Messias, Lord of unitie. Those holy Sonnets they did all agree, With this most lovely Lady here to sing; That by her noble breasts sweet harmony, Their musicke might in eares of Angels ring.

The title “SHAKE-SPEARES SONNETS” has been debated for centuries, yet Emilia Bassano left us a ‘secret code’ over four hundred years ago in Salve Deus Rex Judaeorum:

That we with him t'Eternitie might rise: This pretious Passeouer feed vpon, O Queene, Let your faire Virtues in my Glasse be seene.

This passage refers to the ‘Day of Reckoning’ when the Messiah returns, and the ‘Daughters of Jerusalem’ attend the Marriage Supper of the Lamb, with Shekhinah (the Queen). In particular, this refers to “They will try to escape the terror of the LORD and the glory of his majesty as he rises to shake the earth” (Isaiah 2:21). In Isaiah 2:4, Isaiah foretold how Christ will mediate wars, and they will hammer their חֲנִיתֽוֹתֵ (“spears”) into ploughs for tilling fields. It relates to the essential teaching of not being involved with idol-worship, for one’s neshamah (one of three parts breathed into us by Holy Spirit) can become defiled, and ruin your opportunity to join the Messiah in Marriage Supper of the Lamb. This is the true Zoharic meaning behind the title Shake-speares Sonnets.

The Story Behind the Sonnets

The erotic story of the Rose is not original from Shakespeare’s Sonnets. It originates from an ancient story by Rabbi Shim’on ben Yohai, and his teacher Rabbi Yohanan ben Zakkai Nasi (the Rabban), as was the Tradition to pass these stories down through the generations to this day. It is a blend a Scripture, Jewish Kabbalah (meaning Tradition, later published in the Zohar of Mantua), and a 13th century story added by the 13th century editor, Rabbi Moses ben Shem Tov de León (circa 1240 – 1305AD) of Spain.

The Zohar is the primary source to Shakespeare’s Sonnets, and it was written in Late Jewish Literary Aramaic and Classical Hebrew, first published in Mantua, Italy as Sefer ha-Zohar al ha-Torah (Book of Zohar, on the Torah). The title comes from the Hebrew word זֹ֣הַר (Zohar, Radiance), from the radiance of the sky (Daniel 12:3), and the name of the Second Hall of the Palace of God. The Zohar of Mantua was published in 1558-60, and printing was supervised by Rabbi Isaac Bassano, one of the many rabbinic members of the Bassano family, some of whom were also merchants, musicians, and poets. This story connects directly with the hometown of the Bassano family, and has no connection whatsoever to William Shakespeare.

The original story used by the Spanish translator of the Zohar of Mantua, Rabbi Moses ben Shem Tov de León, is found in the early 13th century, in the history of a small rural village of northern Italy known as Bassan (Latin, later renamed Bassano, then Bassano del Grappa after WWII), after the noble Jewish Bassano family that settled in the region sometime prior to the Pars Liberorum of Bassano (Revolt of the Free of Bassano) in 1259AD. The Bassano family are recorded in the annuls of Bassano del Grappa as one of four noble Bassanese houses: Carrara, Il Vecchio, de Bassan (Bassano), and the Ezzelini family ― the original landowners of the region, since the Placitum of 998AD. A very faded fresco of the Bassano family coat-of-arms remains on display in the Comune di Bassano del Grappa (Bassano del Grappa City Council), as the founding fathers of the city, which grew by the late 16th century to 120 noble families. The Bassano coat-of-arms is the first fresco on the wall, dated 1483 alongside the Ezzelini coat-of-arms and the royal coat-of-arms of King Frederick II and Queen Isabella of Jerusalem. In 1468, a decree of perpetual banishment was issued against all Jews in Bassano, during the time Bassano was ruled by a Podestà on behalf of La Serenissima (Most Serene Republic of Venice). This is interesting, because we know the Bassano family hid as ascetic Franciscan Christians, thereby protecting themselves from expulsion from Bassano in 1476AD and 1509AD, possibly dating back to an agreement with the founding fathers. Hieronymus de Bassanus (Jeronimo Bassano I) was Maestro di Concerti (Concerto Master, composer and/or conductor in that period) at the Basilica Arcicattedrale Patriarcale Metropolitana di San Marco (St Mar’s Basilica), teacher at the Scuola Grande di San Marco (secret confraternity involved in Carnivale, teaching Kabbalah, offering medicine to those who could not afford it, and burying the dead), “Maestro of the trumpets and shawms”, meaning Maestro of the praise unto the King, and those praying for the living, and he served as lecturer at the Seminario Ducale (The Doge’s Seminary), where he was regarded as an expert on “Diminution”. It was the Jews of Venice who assisted the poor in the Scuola Grande di San Marco, supported by both Doges, Antonio Grimani and Andrea Gritti, the latter’s grandson marrying into the Bassano family. The Bassano family of Venezia and England preserved their ancient teachings through their various Venetian confraternities, musical performances, plays, masques, and poetic works, beginning with Hieronymus de Bassanus (Jeronimo Bassano I), though his three youngest sons were all recognized as scholars: Antonio, Giovanni (John), and Giambattista (Baptista).

The Bassano family owned property within the town of Bassano del Grappa, just inside the city gates, along the water’s edge in close proximity to the bridge (“Dal Ponte”, from the bridge), now demolished, and a number of grazing properties for cattle around Bassano, Marostica, Romano d’Ezzelino and Crespano del Grappa, although there is no recorded date they arrived in Bassano, only that it was between 1425-1483AD,[9] because the wealthy Spanish knight and musician Diego de Bassan (~1405-1483AD) settled in Bassano. The earliest coat-of-arms of the Bassano family dating back to the 11th century contains: a crown, a helmet, a two-headed Phoenix, three six-pointed stars (Star of David) over the Tree of Life to the right (Hesed), the yellow lion of Judah with sword, and two white stripes over a red background to the left side, meaning Kabballah Tif’eret (Messiah) balancing Gevurah (Judgment).

The ruler in Bassano del Grappa in 1259AD was Ezzelino III da Romano (Italian), the latter to denote the Italian village of Romano d’Ezzelino about 6 kilometres (3.7 miles) northeast of Bassano del Grappa named after the family, and the Latin word “Romanus”, meaning “a citizen of the Roman Empire”. These are the noble Bassanese families cited in Romeo and Juliet and other Shakespearean plays, because Ezzelino III married Isotta (meaning “the fair”) (also recorded as Selvaggia) daughter of Bianca Maletta (nee Lancia), concubine of the Frederick II, Holy Roman Emperor. Bianca’s father William II Maletta, lord of Pettineo, Sicily, who was well-known to Frederick II.

During this relationship with Bianca, Frederick II married Isabella II (1212–1228AD) in August 1225AD, which was ratified by proxy (not physically present) by Frederick’s Notary and Chamberlain, Richard of San Germano in the City of Acre, days before Isabella II was crowned Queen of Jerusalem. Isabella was the only child of Maria, Marquise of Montferrat, Queen of Jerusalem, and John of Brienne (Prince Consort as Regent). Emilia used this imagery of Frederick II in the Sonnets as an evil disposed man who could not control the evil impulse of Lot (Satan), defiling the Holy Temple of Jerusalem, because Frederick was known to have a relationship with Bianca for up to 20 years while married to various wives. The imagery of the Rose is found in a fresco painted of Frederick II offering a red Rose and two lilies (our Rose-lily). This is the origin of the rose-lily story of the Shake-speares Sonnets, found in the Zohar of Mantua, combined with Scripture which I will now reveal. (Please click on image below to view gallery)

Sources of the Sonnets

There are more than fifty sources to Shake-speares Sonnets, thirty majors, though there are two primary sources used throughout the Sonnets:

- The Mantuan 1558-60 Aramaic and Hebrew Sefer ha-Zohar al ha-Torah (Book of Zohar, on the Torah) literally meaning, “Radiance on the Torah” (the Zohar), printed in three parts in three volumes (188 – 204 x 137 mm), attributed to the 2nd century tannaitic sage Rabbi Shim’on ben Yohai, translated by the scribe Meir ben Ephraim of Padua. It was printed by Jacob ben Naphtali ha-Kohen of Gazolo, though printing was supervised by Rabbi Isaac ben Solomon de Bassan (Rabbi Isaac Bassano) of the Mantuan Synagogue.

- The Thessalonica 1597 “Zohar Hadash” (New Zohar) in two parts in one volume (187x145mm), attributed to the 2nd century tannaitic sage Rabbi Shim’on ben Yohai, printed by Joseph Abraham Ben Sabbatai Mattathias Bath-sheba (Basevi in Italian), son of Sabbatai Mattathias Bath-sheba of Verona. This is the most critical source document of all, because part two deals with the rifts the ‘Dark Lady’ has caused over time, speaking of the shadow side of Shekhinah and compares her in Shir ha-Shirim (Song of Songs) to the women of Israel (daughters of Jerusalem) standing before our Lord on the Day of Judgement – the main theme of Sonnets 127-154.

As you can see by my detailed descriptions above, Zohar Hadash is the primary source document for Sonnets 127-154. The Zohar and Zohar Hadash are early commentaries on the bible, penned by Rabbi Shim’on ben Yohai, from his teacher Rabbi Yohanan ben Zakkai Nasi (the Rabban), as was the קַבָּלָה (Kabbalah), meaning Tradition of the Israelites to this day. Prior to the writing of the Zohar, these traditions were taught orally from master to student. The Bassano family were responsible for the printing of the Zohar, and teaching of the Zohar throughout Italy and the world.

Structure and Theme of the Sonnets

The Sonnets are not broken into three parts as previously assumed. They are broken down into biblical sections, dealing with the Assembly Israel from the time of Creation to their ultimate destiny into our future. Yes, Emilia offers some prophetic insights of what is to come in our future. She intentionally skipped certain books like Noah, dealing with the righteousness of men, because there is an underlying theme in the Sonnets of Bat Torah (women of Torah) versus “evil disposed men”. Below are the sections, with the crescendo to the Sonnets in The Description of Cooke-ham within Emilia Bassano-Lanier’s Salve Deus Rex Judæorum (Hail God, King of the Jews), which was sourced from the Zoharic work of Rav Metivta (Head of the Academy), a prophetic work of the Companions in the Garden of Eden:

The opening verses to Sonnet 1 are found in the opening verses of the Zohar:

From fairest creatures we desire increase, That thereby beauties Rose might neuer die,

Emilia begins her commentary of the Zohar Hadash with “From fairest creatures we desire increase” taken directly from God’s command to Noah and his son’s after Creation, where God blessed Noah and his sons, and commanded them in Genesis 9:1-3 to go forth and increase:

Then God blessed Noah and his sons, saying to them, “Be fruitful and increase in number and fill the earth. The fear and dread of you will fall on all the beasts of the earth, and on all the birds in the sky, on every creature that moves along the ground, and on all the fish in the sea; they are given into your hands. Everything that lives and moves about will be food for you. Just as I gave you the green plants, I now give you everything."

We find the purpose of King Solomon’s Proverb’s was “to teach people to live disciplined and successful lives, to help them do what is right, just, and fair” (Proverbs 1:3), thus we are in principle the “fairest creatures” in Creation with the greatest consciousness for wisdom. The Hebrew word רָבָה transliterated as rabab is translated into English as “increase”, however the English language does not do the Hebrew justice, for it means so much more: great, to become much, to increase, to be fruitful, an infinite absolute potential, and in a feminine sense to brood over as a passionate mother protects her children. It refers to the Assembly of Israel and its potential to produce offspring, prior to the seed, because it consists of both judgement and mercy.

Emilia lays out her first ‘secret code’ in the form of a parable of “a Rose that might never die” speaking figuratively of the Assembly of Israel that will never die. This was taken directly from the opening lines of Rabbi Hizkiyah in Zohar 1:1a:

רִבִּי חִזְקִיָּה פָּתַח, כְּתִיב כְּשׁוֹשַׁנָּה בֵּין הַחוֹחִים.(Rabbi Hizkiyah opened, Like a Rose among the thorns…)

The phrase “beauties Rose might neuer die” is taken from the Scripture: “Like a rose among thorns, so is my beloved among the maidens”. (Song of Songs 2:1-2). In the New Living Translation, the Young Woman declares: “I am the rose of Sharon, the lily of the field” showing that all of the Daughters of Zion (Israel) are the rose-lily. Emilia opened the Sonnets with a declaration of immortality for the world, offering the Holy Grail through Bat Torah (Roses of Torah), literally women of Torah rising up in the Last Days.

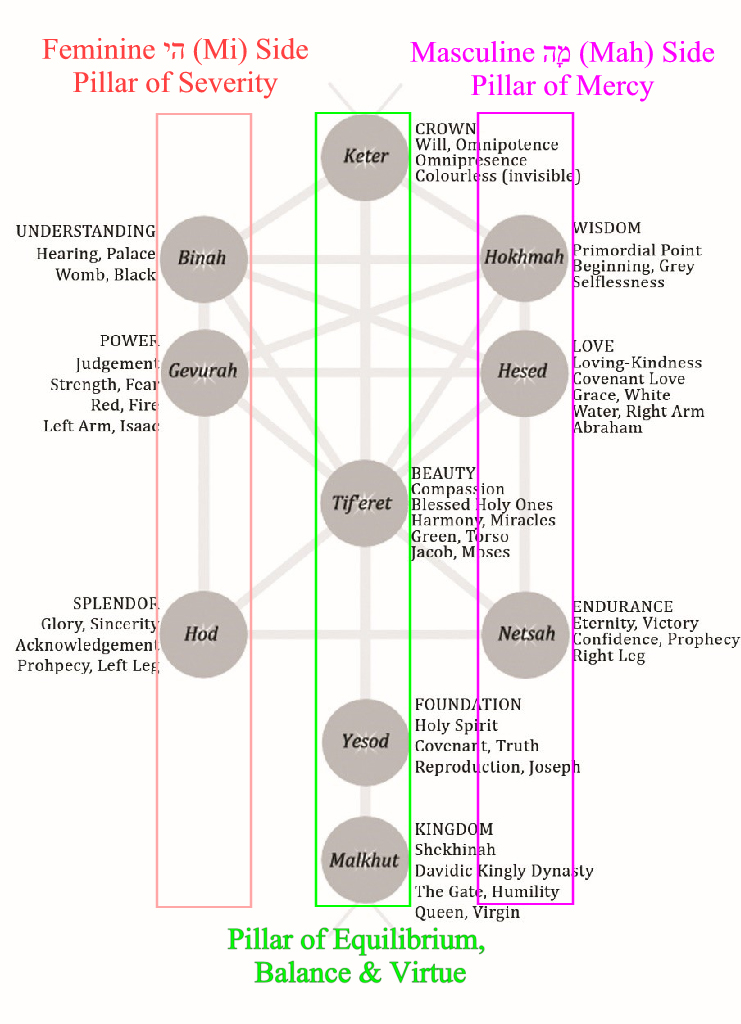

The Real Dark Ladies of the Sonnets

Now let us briefly examine Sonnet 127 that has been completely misrepresented for centuries. The real Dark Lady refers to: שִׁיר הַשִּׁירִים, אֲשֶׁר לִשְׁלֹמֹה (Shlomoh’s Shir ha-Shirim), “Song of Songs, which is Solomon’s” (Song of Songs 1:1), which contains a Large ש (shin), followed by a small ש (shin). Shin refers to the mystery of the מֶרְכַּב (Merkabah), the Upper Chariot, which is comprised of the Patriarchs Abraham, Isaac and Jacob (Hesed, Gevurah, and Tif’eret) that support the three pillars of the Chariot (Binah). “O LORD יְהוָ֥ה (YHVH), our Lord אֲדֹנֵ֑ינוּ (Adonai), your majestic name fills the earth! Your glory is higher than the heavens.” (Psalm 8:1). These are the mysteries of the Upper Chariot: אֲדֹנָי (Adonai), צבאות (Tseva’ot), יהוה (YHVH), and אהוה (Ehyeh) — the Tzadeikis (Holy Woman) or Holy Women in the plural, referring the Armies of the Lord, led by these Holy Women. She is the unsullied, who is deserving of the World to Come! Now try and convince me William Shakspēr wrote the Sonnets — Absolute ignoramuses who are עזי פנים (azzei fanim), brazenfaced, like an ignorant dog that is incapable of understanding”, for it is written: “Like greedy dogs, they are never satisfied. They are ignorant shepherds, all following their own path and intent on personal gain” (Isaiah 56:11) — they have no idea of the real meaning!

King David joins the Patriarchs as the fourth pillar of the Chariot, equating to the fourth mystery of Shekhinah, with Binah as the rider. We see Emilia’s ‘secret code’ in her dedication to the Queen’s Most Excellent Majesty in Salve, where she compares her to Phoebe as “darkest night with her most beauteous face”:

From your bright spheare of greatnes where you sit, Reflecting light to all those glorious stars That wait vpon your Throane; To virtue yet Vouchsafe that splendor which my meannesse bars: Be like faire Phoebe, who doth loue to grace The darkest night with her most beauteous face.

Phoebe in Greek mythology was a female Titaness priestess who received control of the Oracle of Delphi from Themis; thus, she was associated with the sun (shining), a typology of Shekhinah. This is an important ‘secret code’ because these four mysteries known as the Tzadeikis (Righteous Women) that are also recognized by another name: “Dark-and-Not-Dark”, meaning when they are gazed upon, their darkness disappears immediately, for the light of Shekhinah radiates them and shines upon them in every direction. This is why Emilia wrote the famous lines, for black was not counted as fair:

IN the ould age blacke was not counted faire, Or if it weare it bore not beauties name: But now is blacke beauties successiue heire,

Or if it were fair, it bore not Beauty’s name, which we know is the imagery of the Christ (Tif’eret), who “I, Jesus, have sent my angel to give you this testimony for the churches. I am the Root and the Offspring of David, and the bright Morning Star” (Revelation 22:16), alleging He is the light of Shekhinah (Tif’eret in Jewish Kabbalah). The third verse is taken directly from: “I am black, but beautiful, O women of Jerusalem, like the desert tents of Kedar or the curtains in Solomon’s palace” (Song of Songs 1:5), speaking of Adonai, but also the Shulamite woman, and those who would join with her to form Matronita, who is surrounded by Her camp of angels, weaving and constituting her body, protecting Her from demonic forces (the imagery of the thorns of the rose). I will leave you to ponder the dark Divine Mother of the left side of judgement and what that might mean for the world as we know it. The Jewish people according to Kabbalah are to bring light into the world and conquer darkness. Emilia was a light unto the world. Do not let the darkness hold us back. When the Jewish people do as commanded, a flow of blessing comes into all of the world. This is your role Israel!

Crescendo

Emilia builds upon a foundation from Sonnet 1, all the way through to Sonnet 154 on the final destiny of mankind, then the Crescendo is found in The Description of Cooke-ham in Salve Deus Rex Judaeorum, a prophetic work of the Companions (angels) in the Garden of Eden, with overlays from another Zoharic portion on the luminous darkness with the arrival of Adam in the Garden of Eden, the canopies, and the prayers and songs to ensconce Shekhinah. The end of the seventh millennia is not the end; it is the final judgement of the wicked. Daniel prophesied: “But in the end, the holy people of the Most High will be given the kingdom, and they will rule forever and ever” (Daniel 7:18), meaning forever ruling with Christ, as expounded in Emilia’s Description of Cooke-ham, which foolish scholars have taken literally to describe Cookham, England.

Afterword or Swan Song?

Herein I have offered an opening teaser to my major academic work of A Comprehensive Commentary of SHAKE-SPEARES SONNETS in the hope you gain interest in the topic and to prove the origin of the Sonnets. Many years ago, when I first began my research into the Sonnets, I knew the Sonnets were a biblical commentary, but I could not follow the trail until I researched the Bassano family and their connection to the Zohar of Mantua. I have studied Kabbalah for many years, and I have found it both interesting and challenging, because I am not Jewish, although I have extensive training in religion, theology, and philosophy. I am an Ordained Minister in the Christian Church, though I have never held the position of pastor of a Church, because my goals have always been academically minded. To use a Bassano expression, my desire is for professors, researchers, and students to “explore in the valley of secrets” and I am confident you will begin to love the sweetness of spirit that comes with such research. I have included research from Tomes 2 and 3 in this academic paper, even though they are not yet published. I wrote this paper when COVID entered my town of Stanthorpe for the first time in January 2022, just in case I came down with COVID and my later research may not be published. My family retain my uncompleted manuscripts, so that later scholars can continue my research and discover the real poet of the Sonnets, Emilia Bassano-Lanier. Please dig deeper and discover who Emilia Bassano-Lanier really was, and how these tragic events shaped her life to teach us all today. Her prophetic utterances within each Sonnet can teach us how to overcome what is to Come.

Dr Peter D Matthews

A link to my book: https://www.amazon.com.au/Comprehensive-Commentary-SHAKE-SPEARES-SONNETS/dp/0992285798/

Bibliography

‘‘‘A Cambridge Alumni Database: Marlowe, Christopher (MRLW580C), BA 1584, MA 1587’. University of Cambridge, 1584.